In the 1800s and early 1900s, waves of immigrants came to American cities to escape famine or persecution in their home countries. On New York’s Lower East Side, mostly Irish and Italians were packed into airless, crowded tenements or makeshift shelters, where they lived in extreme poverty. Under these miserable conditions, diseases spread quickly, making orphans of many children. Other children were placed in orphanages by parents who could no longer feed or care for them. Some children were simply abandoned and survived on the streets as best they could, often as petty thieves.

This tragic situation inspired Charles Loring Brace to help these homeless children by starting the Children’s Aid Society in 1853. He planned to give children from the teeming city streets and orphanages a chance at adoption in rural communities. They were bathed, dressed in new clothes, and sent out of New York by train for new and better lives. Brace believed the children needed to make a clean break with the past. No keepsakes were permitted. Parents and children could not keep track of each other, though siblings adopted separately were allowed to keep in touch.

This tragic situation inspired Charles Loring Brace to help these homeless children by starting the Children’s Aid Society in 1853. He planned to give children from the teeming city streets and orphanages a chance at adoption in rural communities. They were bathed, dressed in new clothes, and sent out of New York by train for new and better lives. Brace believed the children needed to make a clean break with the past. No keepsakes were permitted. Parents and children could not keep track of each other, though siblings adopted separately were allowed to keep in touch.

From a very few up to three hundred children, babies through age fourteen, went on each train. Agents from the Children’s Aid Society supervised and encouraged them as they traveled. The trip could last a few days or several weeks.

Crowds of people waited at each stop. Some planned to adopt, and some came just for the entertainment of watching children being chosen. Many children were welcomed into happy new families. Others were mistreated. Some became farm laborers or maids. Their stories and experiences were as different as the more than one hundred thousand individual children who rode the trains between 1854 and 1930.

By the 1930s, new programs to help children and immigrants and new laws to control adoption brought the orphan trains to an end.

Kentucky had its own version of the Orphan Train. From 1895 to 1936, thousands of children—many from the hills and hollows of eastern Kentucky—were transported to new homes or to the Kentucky Children’s Home in Louisville. From there, they were adopted in homes across the state. For more information, see Suzan Morris Ledford’s article, “The Kentucky Orphan Train,” in the May 3, 2022 issue of Kentucky Monthly.

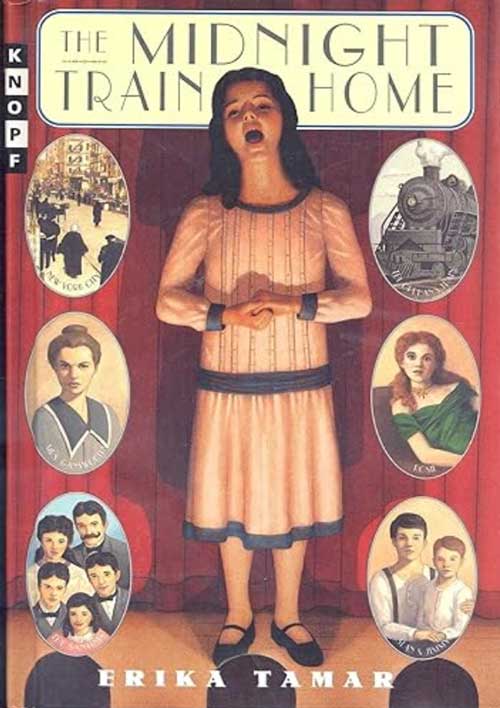

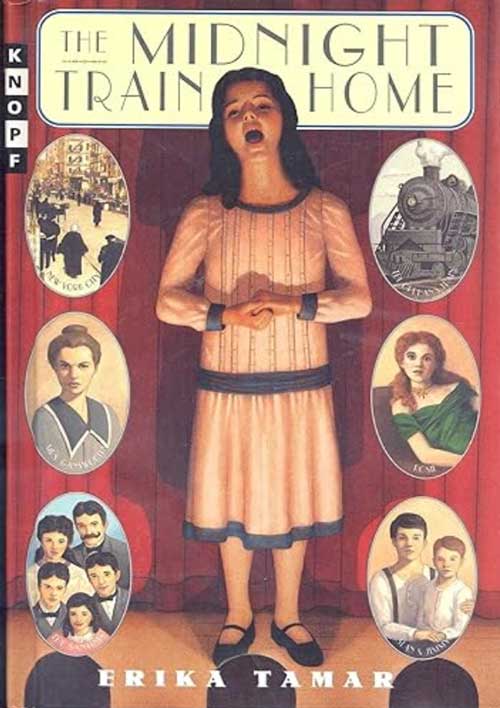

Erika Tamar’s book, “The Midnight Train Home” is a novel that traces three siblings, Deidre O’Rourke, age 11, and her brothers Sean, age 13, and James, age 3. They were living on the street in New York when their mother made the painful decision to surrender her three children to the Children’s Aid Society. Follow these three fearful yet hopeful children as the orphan train takes them to a new life. I just finished reading this book and I recommend it for teenagers and adults. It will make you grateful to have a family.

“The Midnight Train Home” is available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore, 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

James M. Gifford, Ph.D.

CEO & Senior Editor

Jesse Stuart Foundation

In the 1800s and early 1900s, waves of immigrants came to American cities to escape famine or persecution in their home countries. On New York’s Lower East Side, mostly Irish and Italians were packed into airless, crowded tenements or makeshift shelters, where they lived in extreme poverty. Under these miserable conditions, diseases spread quickly, making orphans of many children. Other children were placed in orphanages by parents who could no longer feed or care for them. Some children were simply abandoned and survived on the streets as best they could, often as petty thieves.

This tragic situation inspired Charles Loring Brace to help these homeless children by starting the Children’s Aid Society in 1853. He planned to give children from the teeming city streets and orphanages a chance at adoption in rural communities. They were bathed, dressed in new clothes, and sent out of New York by train for new and better lives. Brace believed the children needed to make a clean break with the past. No keepsakes were permitted. Parents and children could not keep track of each other, though siblings adopted separately were allowed to keep in touch.

From a very few up to three hundred children, babies through age fourteen, went on each train. Agents from the Children’s Aid Society supervised and encouraged them as they traveled. The trip could last a few days or several weeks.

Crowds of people waited at each stop. Some planned to adopt, and some came just for the entertainment of watching children being chosen. Many children were welcomed into happy new families. Others were mistreated. Some became farm laborers or maids. Their stories and experiences were as different as the more than one hundred thousand individual children who rode the trains between 1854 and 1930.

By the 1930s, new programs to help children and immigrants and new laws to control adoption brought the orphan trains to an end.

Kentucky had its own version of the Orphan Train. From 1895 to 1936, thousands of children—many from the hills and hollows of eastern Kentucky—were transported to new homes or to the Kentucky Children’s Home in Louisville. From there, they were adopted in homes across the state. For more information, see Suzan Morris Ledford’s article, “The Kentucky Orphan Train,” in the May 3, 2022 issue of Kentucky Monthly.

Erika Tamar’s book, “The Midnight Train Home” is a novel that traces three siblings, Deidre O’Rourke, age 11, and her brothers Sean, age 13, and James, age 3. They were living on the street in New York when their mother made the painful decision to surrender her three children to the Children’s Aid Society. Follow these three fearful yet hopeful children as the orphan train takes them to a new life. I just finished reading this book and I recommend it for teenagers and adults. It will make you grateful to have a family.

“The Midnight Train Home” is available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore, 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

James M. Gifford, Ph.D.

CEO & Senior Editor

Jesse Stuart Foundation