This article was originally published in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly and is republished on this website with permission.

Jesse Stuart (1906–1984), one of Appalachia’s most famous native sons, published more than 2,000 poems, 460 short stories, hundreds of essays, and sixty-four books describing a fast-dwindling mountain culture and the natural world that framed it. A regionalist often compared to William Faulkner for his sharp focus on a single poor county, Stuart began his career—like most young writers—without a distinct voice or sense of place.1 As a graduate student of English literature at Vanderbilt University from 1931 to 1932, however, he struck out on his own path that led to resounding success. Throughout his long life, Stuart named Vanderbilt professor Donald Davidson as his most enthusiastic editor and friend during his early career.

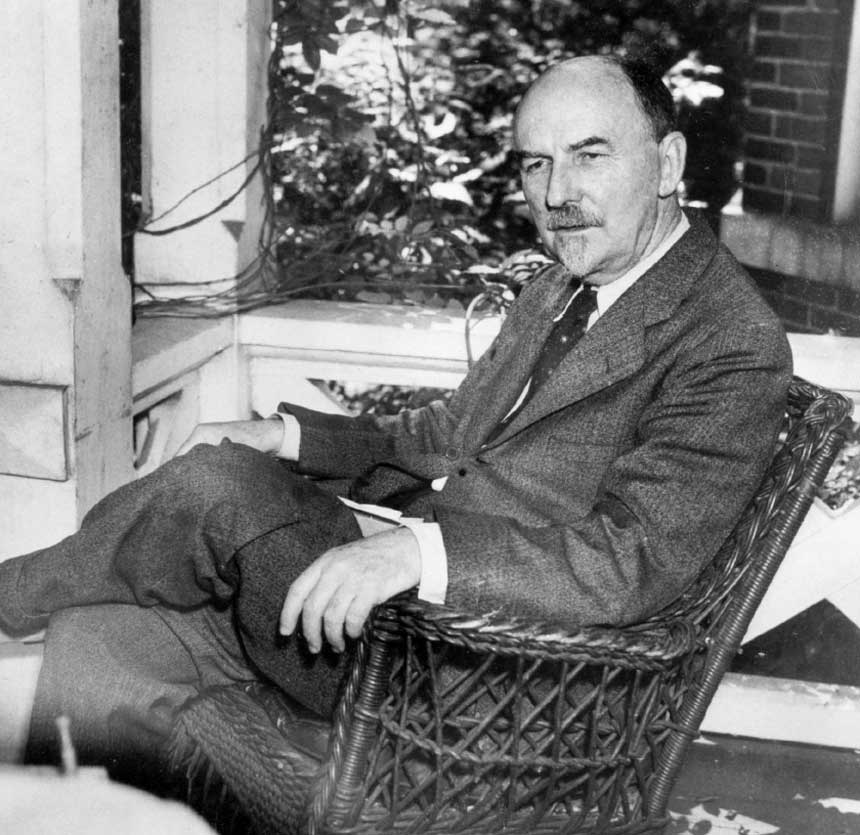

Born in Campbellsville, Giles County, Tennessee, in 1893, Davidson attended a small grammar school where his father was the principal. At home, the schoolmaster encouraged his son to study classical literature, languages, and Tennessee folklore. When Davidson was old enough, he moved to Nashville and enrolled at Branham and Hughes Military Academy, a preparatory school with links to Vanderbilt; from there, he entered Vanderbilt on a scholarship in 1909. After his freshman year, he took four years to teach in country schools and earn tuition money. Davidson returned to Vanderbilt in 1914, earned his degree in 1917, served as an army officer in France during World War I, and later became a professor at his alma mater.

Donald Grady Davidson after his return to Vanderbilt University. Donald Davidson, c. 1926. Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives, Nashville.

Before the war, he had become part of a group that met informally at playwright Sidney Mttron Hirsch’s house in Nashville to discuss politics and literature. When Davidson returned home in 1920, his frequent meetings with Hirsch and other young intellectuals resumed. Writers and students such as Robert Penn Warren and Allen Tate soon joined the group and, for three years, published a poetry magazine. The Fugitives, as they were known, occasionally used sophisticated language to deal with themes such as isolation, aging, and death, though they were more comfortable with more traditional, regional writing. Their shared common aesthetic and “sense of the age” had a profound impact on the American literary scene.2

In 1928, Harcourt, Brace and Company published an influential collection of their work, Fugitives: An Anthology of Verse. At that time, Jesse Stuart was an undergraduate at Lincoln Memorial University (LMU) in Harrogate, Tennessee.3 A determined young writer from the hollows of Greenup County, Kentucky, Stuart had grown up as one of five children on an isolated hill farm, taught in one-room schoolhouses, and worked in a local steel mill. At LMU, he grew enamored with the Fugitives’ work, particularly their imagery of and ambivalence toward the South. Stuart was not of Old South plantation stock; he was instead wrought out of the Appalachian mountain foothills. But in the late 1920s and early 1930s, he wanted to flee his rural upbringing and earn an education that would set him apart from his Greenup County neighbors. Although he later changed his mind, Stuart declared in 1928 that he would “never never settle…with [his] kins people. Strangers are much better and…not quite so quarrelsome.”4

In How They Shine, Katherine Vande Brake comments on the challenges Appalachian students face after pursuing a higher education. She observed that they sometimes go back to their mountain homes and kin and sometimes do not. Whether they return or not, these per-sons are so radically reoriented in terms of and practice by their educations that they cannot reintegrate into mountain communities. They have trouble sorting out their values—deciding what is really important to retain from the culture in which they were raised.5

Stuart was struggling with that very issue when he was introduced to the Fugitives, who had a dynamic, contradictory relationship with their own heritage. It is not surprising that he felt a connection with their poetry and essays. Two years after graduating from LMU, he borrowed $150 from the local bank and headed for Nashville, then the cultural epicenter of his dreams. In summer 1931, Stuart took classes at the George Peabody College for Teachers and “went across the street” to enroll in Vanderbilt’s graduate program. Stuart poured out his difficulties and ambitions to the English Department chairman Dr. Edwin Mims and gained admission.6

Dr. Edwin Mims helped Stuart gain admission into Vanderbilt’s graduate program. John Hood. Dr. Edwin Mims, c. 1930s. Photographic Archives, Vanderbilt University, Nashville.

By the time he enrolled, he had already paid to have a book of poems published with a vanity press in Howe, Oklahoma. A collection of “high school, steel mill, and college poems written between the ages of fifteen and twenty-two,” Harvest of Youth was a complete failure. “You know when I got that book out of the box I almost vomited,” he remembered. “They had paper backs—thin paper. And it was just terrible. I got sick to my stomach. Just real sick.” The poems were even worse than the binding, and Stuart burned most of the copies after his Vanderbilt classmates ridiculed his “literary sin.”7 But at Vanderbilt, he was determined to become a better writer under the famous men who had inspired him.

Stuart, however, was scholastically unprepared for a prestigious graduate program at an institution with privileged students and rigorous standards. His personal philosophy was that “poetry will tell you to let the term papers go to hell”.8 Of course, this did not sit well with the professors who had assigned the term papers. He made poor grades but was also a charming and intelligent young poet. It was not long before his professors and fellow students invited him to Hirsch’s gatherings.

The group, though, never fully embraced Stuart or his poems. He was a font of paeans to Kentucky soil and persimmon trees. He observed and recorded the world around him but did not analyze it like the Fugitives did, certainly not in terms of classical antiquity and linguistics. In a later tribute to Stuart, Ruel E. Foster compared him to the mythical giant Antaeus: “invincible so long as he is touch-ing the earth and people.”9 Foster asserted that the Fugitives saw themselves as influenced by, but ironically detached from, the earth and people. Stuart was conflicted. Despite feeling alienated from both his homeplace and this new world at Vanderbilt, he could not entirely feign detachment from the land and people of his youth. It was a cruelly ironic mismatch. When Stuart finally discovered that most men in the group had little more than a patch of tomatoes they called farms, he became disillusioned. Theoretical views about the values of farming meant little to him, whose own life had depended on it. Then, in the middle of the school year, Stuart’s partially completed master’s thesis on John Fox Jr. along with his clothing, several subpar term papers stamped with failing grades, and his typewriter all burned in a dormitory fire.10

Wesley Hall, which burned in 1932. Wesley Hall, 1930. Photographic Archives, Vanderbilt University, Nashville.

Stuart was almost ready to quit when Davidson, his Elizabethan poetry professor, came to his aid. Among the Fugitives, Davidson was “the most convinced Southerner, the least ironic in his loyalty to the ‘Sanctuary’ of the Southern wilderness and the ‘Hermitage’ built by his forefathers.”11 Having grown up in rural Tennessee and taught in rural schools, he was an ideal mentor for Stuart. In Where No Flag Flies, Mark Royden Winchell suggests Davidson may have “seen in Stuart an exaggerated version of some aspects of his earlier self.”12

When the school year ended in summer 1932, Stuart had not completed all his assignments or submitted his required master’s the-sis. Although he had earned a C in Davidson’s class, the professor liked the poems Stuart had slipped under his door. As one of the first to “[open] himself enough to be touched by Stuart’s latent worth,” Davidson could see that the young poet did not need to be in graduate school imitating other writers.13

In a conversation Stuart recounted ad nauseam in books and essays, Davidson advised him, “Go back to your home…and write of your county as Yeats and Joyce have written of Ireland, Scott, Burns, and Barrie have writ-ten of Scotland, Undset has written of Sweden, Knut Hamsun has written of Norway.”

“Those writers are giants,” Stuart replied.

“You can be a giant, too,” said Davidson, suggesting Stuart send his poem “Elegy for Mitch Stuart” to H. L. Mencken, editor of the American Mercury.

“I can’t even make the little magazines,” said Stuart. “How can I make this nationally known publication? Besides…Mencken said there’s not anybody in America writing poetry fit to print.”

“His bark is bigger than his bite,” Davidson promised. “Send it. You’re not for the little magazines. You’re for the big ones.”14

After his disastrous experiment in higher education, Stuart left Vanderbilt in summer 1932 and returned home to hone his own writ-ing technique; yet, he considered the entire year worthwhile because he had met that one great teacher, Donald Davidson.15 He also quit for financial reasons. He needed the money a publication would bring and craved approval from Mencken, a notoriously cantankerous editor.

“Elegy for Mitch Stuart” appeared on the pages of the American Mercury in January 1933, after Davidson had helped “smooth out some wrinkles” and fit it with a rhyme scheme.16 Because he intuited that Stuart’s ego could not handle harsh commentary and that his poetry’s significance was not literary, Davidson did not criticize the work directly. His editorial hand was light but immeasurably valuable, and any-way, he wondered, “How do you criticize or teach a flowing river?”17

In October 1933, large sequences of Stuart’s poems appeared in both the American Mercury and the Virginia Quarterly Review, the latter edited by Stringfellow Barr. Mencken praised Stuart’s contributions as being “among the most interesting things that the magazine [had] printed.” Two years later, Stuart sent Mencken an autographed copy of his first book of poetry, Man with a Bull-Tongue Plow.”18

Stuart’s book was largely the result of Davidson’s critiques and networking. He painstakingly read and edited all the sonnets, helped mold them into more economical and lyrical verses, and then suggested potential magazines for publication based on his instincts and knowledge of the industry. Davidson had approached Barr, vouching for Stuart as “the first real poet…ever to come out of the southern mountains.”19 Old debate opponents, Barr and Davidson had a mutual respect, so Barr agreed to consider the rough-hewn poems. After selecting a sequence of twelve, Davidson wrote Stuart an encouraging letter: “If I were a book publisher, I’d like to bring out a book of them…[W]ith your permission, I may succeed in interesting some publisher in seeing them.”20 The book became a wildly popular volume of 703 poems on which E. P. Dutton “spared no expense.”21 Davidson proudly called the book “a triumph” and “a really grand first appearance for a poet to make.”22

Davidson was absorbed in Stuart’s poetry. “Since ‘Fugitive Days,’” he confessed, “I don’t think I’ve seen any poetry by a Southern poet that has gotten hold of me as yours has.”23 Even after the publication of Man with a Bull-Tongue Plow, when Stuart’s career had gathered momentum, Davidson continued to mentor him. He taught Stuart to keep carbon copies of his work and a record of his submissions. He noted which editors paid well or took “a rather special interest in new comers.” He also promoted Stuart’s work among his influential friends, who had greeted it with “genuine interest and…some warm admiration” since 1932.24 Before and after the success of his first book, Stuart was often discouraged by poor reviews or a magazine rejection. Davidson reminded him to be patient: “Things mustn’t go too fast—they never do for the greatest souls.” It was impossible to predict which poems would be accepted and in which direction the market would lean next, but Davidson assured him it was simply a matter of waiting and rewriting.25

Stuart conspicuously and proudly lacked the faculty of self-editing. Throughout his life, he frequently claimed that he had never reread a single one of his books after it had been writ-ten. Davidson admonished him to “criticize your own verse” rather than leaving everything to “spontaneous and infectious inspiration.” He was sure Stuart had “something to say to people” but, in agreement with other critics, knew that his poetry was too repetitious and technically flawed to be read as serious attempts at literature. To achieve “continuous excellence” rather than “spotty success,” Davidson advised Stuart to expend more effort on revisions and carefully consider input from magazine editors.26 Stuart’s strengths, though, did not lie in his use of language but in his connection with people and reality.

While “so many writers (so-called) have truly lived only in their minds,” Davidson felt that Stuart had “lived in the world of people.”27 For Davidson, it was especially important that Stuart’s poetry be seen by both workaday readers and intellectuals—and that Stuart not be spoiled by his popularity. He warned against catering to the metropolitan East’s “special kind of interest” in the Appalachian Mountains. It was “partly sentimental and romantic, partly exploitatory and commercial” and capable of “warp[ing]” Stuart from his “true steady course.”28

“You have read the life of Robert Burns and will know what I mean,” Davidson explained. “Also, if you have followed such men as Erskine Caldwell…you will be able to make the con-temporary application. They write ‘Southern’ books for ‘Northern’ audiences.” He suggested that Stuart look to Robert Frost, who had “not allowed New York to twist him off key.”29

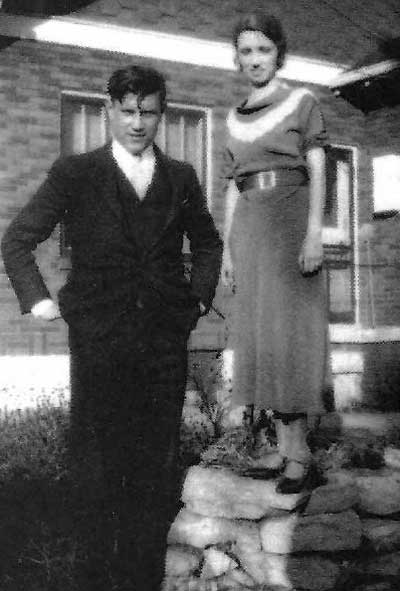

Stuart greatly appreciated Davidson’s help and—as he did with many friends and acquaintances—peppered him with difficult questions that had nothing to do with literature. In 1933, he was furious about local political influences on education in Greenup County and flooded his former professor with rants. Davidson cautioned Stuart to restrain himself and channel his “strong feeling” into a poem rather than a fistfight.30 But Davidson did not have all the answers. Moved by Stuart’s struggle to make a decision about his longtime girlfriend Elizabeth Hale, Davidson could say only that it was “something a man must decide for himself. The long and short of it is that I may be able to advise you a little on literary problems, but not on marriage. And there I must let the matter stand.”31

Jesse Stuart and Elizabeth Hale resided in Nashville in the early 1930s. Jesse Stuart and Elizabeth Hale in Nashville, 1932. Photographic Archives, Vanderbilt University, Nashville.

As Stuart grew as a man and a writer, his relationship with Davidson evolved into a more balanced friendship, with free-flowing advice, personal chatter, and professional respect. In 1936, Davidson reminded Stuart, “You have nothing to complain about if you’re selling poetry and prose.”32 Two years later, when Stuart was a Guggenheim Fellow in Scotland working on his first autobiography, Beyond Dark Hills, he asked Davidson about how to handle using real names in the book. By the end of the decade, Davidson was congratulating Stuart on his marriage to Naomi Deane Norris, the publication of his first novel, and news that a student was writing his master’s thesis on Stuart.33

Stuart’s fame waxed as Davidson’s waned. Stuart eventually found himself in the position of offering publication advice to the man who had essentially launched his career. Davidson was trying to find a publisher for his manuscript about the country music business. It had been rejected by both Scribner’s and Rinehart and Company. In November 1953, Stuart suggested he try McGraw-Hill, which had published recent Stuart books such as Clearing in the Sky and Hie to the Hunters. The editors there liked Davidson’s book and “even seemed on the verge of publishing it when the firm summarily abolished its trade division.”34 Davidson’s The Big Ballad Jamboree was eventually published posthumously in 1996 by the University Press of Mississippi.

Davidson was right to take his protégé’s advice. By 1953, Stuart had published seven-teen regionally focused books, all of which had been well-received. The professor’s vision of his former student as a voice of the people was fully realized on October 15, 1955, when Kentucky declared an official “Jesse Stuart Day.” Mark Royden Winchell felt that “Davidson prob-ably envied Stuart this local honor more than he would have the international reputation of other artists.”35 Stuart had tasted larger literary success, too, crystallized in the acceptance of one no less than Robert Frost. Once more, Stuart had Davidson to thank. In summer 1953, he had persuaded Stuart to give a speech at the famous Bread Loaf School of English, in Ripton, Vermont, the oldest writer’s conference in the country. Frost, who almost always avoided lectures, attended Stuart’s talk and gave it rare praise. As for Davidson, he was “carried away” and reported that other “high-powered…intellectual[s]” in attendance were “completely captivated.”36

Davidson’s death in 1968 left Stuart “with thoughts too deep for words, and he wrote nothing of his tears.”37 Four years later, Stuart’s autobiography was reprinted by McGraw-Hill; written at Vanderbilt in from 1931 to 1932 and originally published in 1938, the revised edition contained several glowing pas-sages about his relationship with Davidson. In a new foreword, Stuart called Davidson “one of the greatest, if not the greatest, teachers I had ever known…Vanderbilt was worth the year of suffering and hardships to have this one great teacher.”38

ENDNOTES

1. J. Donald Adams, “Speaking of Books,” New York Times Book Review, Oct. 20, 1963, 2.

2. William Pratt, “In Pursuit of the Fugitives,” in The Fugitive Poets: Modern Southern Poetry in Perspective, ed. William Pratt (Nashville: J. S. Sanders and Company, 1991), xiii–xlviii.

3. Donald Davidson, ed., Fugitives: An Anthology of Verse (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1928).

4. Jesse Stuart to Mitchell Stuart, n. d., 1928, James

M. Gifford personal collection, Jesse Stuart Foundation, Ashland, KY. Many of the letters cited in this article are in the personal collection of the author, these will hereafter be cited as in the JMG personal collection.

5. Katherine Vande Brake, How They Shine: Melungeon Characters in the Fiction of Appalachia (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2001), 117.

6. Jesse Stuart, “Three Teachers and a Book,” in Pages: The World of Books, Writers, And Writing, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli and C. E. Frazer Clark (Detroit: Gale Research, 1976), 101.

7. H. Edward Richardson, Jesse: The Biography of an American Writer—Jesse Hilton Stuart (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984), 119. Honest Confessions of a Literary Sin was first published in 1977 (Detroit:

W- Hollow Books) as a twenty-four-page hardback issued without a dust jacket. In 1998, this brief narrative about the private publication of his first book was reissued.

8. Jesse Stuart, Beyond Dark Hills (Ashland, KY: Jesse Stuart Foundation, 1996), 281.

9. Ruel E. Foster, “Literary Tribute to Jesse Stuart,” West Virginia Hillbilly (Richwood, WV), Jan. 24, 1976.

10. Frank Leavell, “Jesse Stuart at Vanderbilt,” Jack London Newsletter 10, no. 2 (May–Aug., 1977), 84–93.

11. William Pratt, “In Pursuit of the Fugitives,” xiii–xlviii.

12. Mark Royden Winchell, Where No Flag Flies (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2000), 185.

13. Frank Leavell, “Jesse Stuart at Vanderbilt,” Jack London Newsletter 10, no. 2 (May–Aug. 1977): 85.

14. H. Edward Richardson, Jesse, 171; Jesse Stuart, “Three Teachers and a Book,” 102.

15. Jesse Stuart, Beyond Dark Hills, xiii, 281; To Teach to Love (Ashland, KY: Jesse Stuart Foundation), 143.

16. Richardson, Jesse, 152. In an “Editorial Note” that accompanied “Elegy for Mitch Stuart,” Jesse Stuart thanks both Donald Davidson and Robert Penn Warren for their help and encouragement.

17. Donald Davidson to Everetta Love Blair, Mar. 27, 1953, JMG personal collection.

18. H. L. Mencken to Jesse Stuart, Oct. 9, 1933 and Feb. 15, 1935, JMG personal collection. Jesse Stuart, Man with a Bull-Tongue Plow (New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, 1934).

19. Donald Davidson to Stringfellow Barr, June 3, 1933, JMG personal collection.

20. Stringfellow Barr to Jesse Stuart, July 1, 1933, JMG personal collection.

21. Ad in Publisher’s Weekly, Sept. 15, 1934.

22. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Sept. 24, 1934, JMG personal collection.

23. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart from Marshallville, GA, Mar. 1, 1933, JMG personal collection.

24. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Jan. 20, 1934 and Feb. 19, 1934; Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Aug. 12, 1932, JMG personal collection.

25. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Nov. 22, 1933; Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, July 1932, JMG personal collection.

26. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Aug. 12, 1932, JMG personal collection.

27. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, July 4, 1932, JMG personal collection.

28. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Nov. 22, 1933; Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, July 1932, JMG personal collection.

29. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Feb. 19, 1934, JMG personal collection.

30. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Mar. 27, 1933 and Nov. 6, 1932, JMG personal collection.

31. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Apr. 18, 1933, JMG personal collection.

32. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Dec. 14, 1936, JMG personal collection.

33. Donald Davidson to Jesse Stuart, Nov. 26, 1939, JMG personal collection.

34. Mark Royden Winchell, Where No Flag Flies (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000), 276.

35. Ibid., 350.

36. Richardson, Jesse, 249–50.

37. Ibid., 423.

38. Jesse Stuart, Beyond Dark Hills, 15.