On March 9, 1976, just before noon on a cold and cloudy day in the coal fields of Eastern Kentucky near Oven Fork in Letcher County, the Scotia mine exploded. The day shift that morning had a crew of 106 men, working six sections of the mine. Almost all of them quickly escaped from the mine after the explosion. But fifteen men, last known to have been working in the Two Southeast Mains section, three- and one-half miles underground, were unaccounted for. They were young men, most still in their twenties.

A coal mine explosion was not then, and still is not, an uncommon event for coal miners and their families. But the Scotia mine explosion would be different, changing the lives of fifteen young women forever. As the “Philadelphia Inquirer” put it:

A coal mine explosion was not then, and still is not, an uncommon event for coal miners and their families. But the Scotia mine explosion would be different, changing the lives of fifteen young women forever. As the “Philadelphia Inquirer” put it:

“They were local girls, fifteen of them, who had married local boys in that beautiful and blighted corner of the world called Appalachia. They lived in trailers and frame row houses in coal country, where poor folks still pile coal in the yard as they wait for winter to whirl down the hills. They did not know one another, although their husbands worked the smoldering Scotia Coal mine at Oven Fork. But coal paid the freight of their lives, put cornbread on their tables, and put sooty minstrel faces on their men as they left the mine each day. And coal would thrust the women together, made them lasting friends for life in a way they never dreamed. It would make them coal widows when the Scotia mine blew on the dank, gray morning of March 9, 1976. Coal widows are almost as common as lunch pails in Eastern Kentucky. What happened to these fifteen widows had never happened in the Kentucky coals fields. They became, through a remarkable twist of circumstance, the widows who sued the coal company – and won.”

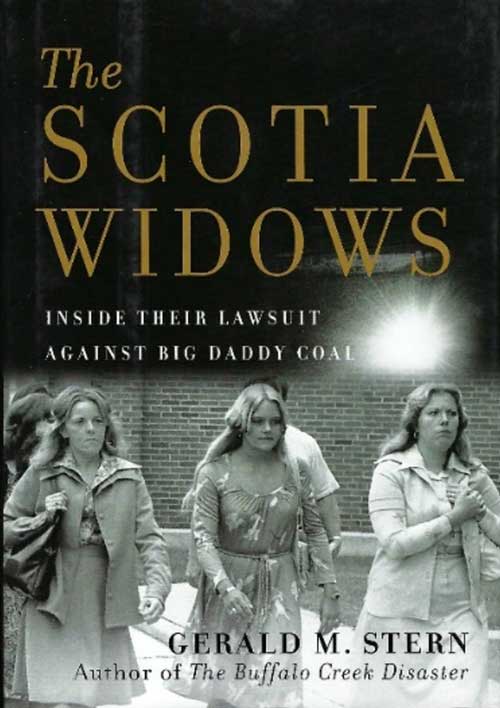

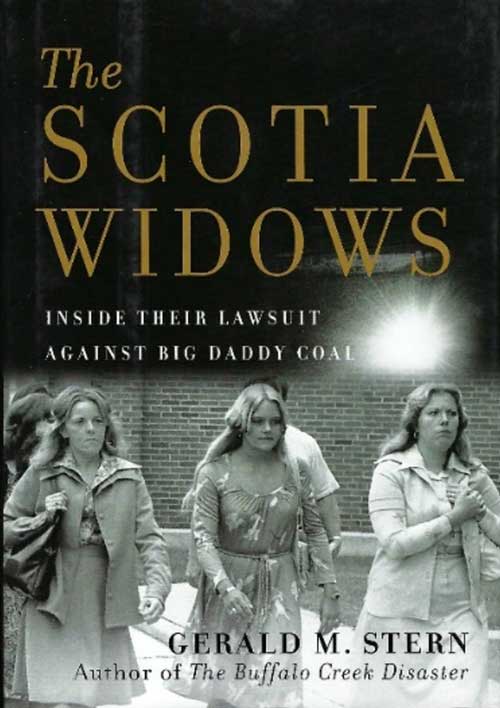

In “The Scotia Widows: Inside their Lawsuit Against Big Daddy Coal,” Gerald M. Stern, the groundbreaking litigator and acclaimed author of “The Buffalo Creek Disaster,” recounts the epic four-year legal struggle waged by the widows in the aftermath of the disaster. Stern shares a story of loss, scandal, and perseverance – and the plaintiffs’ fight for justice against the titanic forces of “Big Daddy Coal.”

Confronted at nearly every turn by a hostile judge and the scorched-earth defense of the Scotia’s mine’s owners, family members also withstood the criticisms of some of their neighbors, most of whom relied on coal mining for their livelihoods. Meanwhile, Stern, representing the widows of the disaster on contingency, amassed huge bills and encountered a litany of formidable obstacles. The Eastern Kentucky trial judge withheld disclosure of his own personal financial interest in coal mining, and a popular pro-coal former Kentucky governor served as the lead defense counsel. The judge also suppressed as evidence the federal mine study that pointed to numerous safety violations at the Scotia mine: In a rush to produce more coal, necessary ventilation had been short-circuited, miners had not been trained in the use of self-rescue equipment, and ventilation inspections had not been made. Moreover, Scotia did not even have a trained rescue team. Ultimately, the Scotia widows’ ordeal helped to inspire the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, which changed safety regulations for coal mines throughout the country.

“The Scotia Widows” portrays in gripping detail young women deciding to pursue a landmark legal campaign against powerful corporate interests and the judge who protected them. It is a critically important and timeless story of how ordinary people “can sometimes find justice in the courtroom.”

“The Scotia Widows” is the August selection for the Jesse Stuart Foundation book group, the Regional Readers. The group will meet on August 31 in the JSF Conference Room. Coffee and conversation at 2:00 pm; book discussion begins at 2:30 pm. Participants will wear face masks and practice social distancing. The book group is open to all.

“The Scotia Widows” and other books about coal mining in Kentucky are available in the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore and Gift Shop at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, call 606.326.1667 or e-mail jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

On March 9, 1976, just before noon on a cold and cloudy day in the coal fields of Eastern Kentucky near Oven Fork in Letcher County, the Scotia mine exploded. The day shift that morning had a crew of 106 men, working six sections of the mine. Almost all of them quickly escaped from the mine after the explosion. But fifteen men, last known to have been working in the Two Southeast Mains section, three- and one-half miles underground, were unaccounted for. They were young men, most still in their twenties.

A coal mine explosion was not then, and still is not, an uncommon event for coal miners and their families. But the Scotia mine explosion would be different, changing the lives of fifteen young women forever. As the “Philadelphia Inquirer” put it:

“They were local girls, fifteen of them, who had married local boys in that beautiful and blighted corner of the world called Appalachia. They lived in trailers and frame row houses in coal country, where poor folks still pile coal in the yard as they wait for winter to whirl down the hills. They did not know one another, although their husbands worked the smoldering Scotia Coal mine at Oven Fork. But coal paid the freight of their lives, put cornbread on their tables, and put sooty minstrel faces on their men as they left the mine each day. And coal would thrust the women together, made them lasting friends for life in a way they never dreamed. It would make them coal widows when the Scotia mine blew on the dank, gray morning of March 9, 1976. Coal widows are almost as common as lunch pails in Eastern Kentucky. What happened to these fifteen widows had never happened in the Kentucky coals fields. They became, through a remarkable twist of circumstance, the widows who sued the coal company – and won.”

In “The Scotia Widows: Inside their Lawsuit Against Big Daddy Coal,” Gerald M. Stern, the groundbreaking litigator and acclaimed author of “The Buffalo Creek Disaster,” recounts the epic four-year legal struggle waged by the widows in the aftermath of the disaster. Stern shares a story of loss, scandal, and perseverance – and the plaintiffs’ fight for justice against the titanic forces of “Big Daddy Coal.”

Confronted at nearly every turn by a hostile judge and the scorched-earth defense of the Scotia’s mine’s owners, family members also withstood the criticisms of some of their neighbors, most of whom relied on coal mining for their livelihoods. Meanwhile, Stern, representing the widows of the disaster on contingency, amassed huge bills and encountered a litany of formidable obstacles. The Eastern Kentucky trial judge withheld disclosure of his own personal financial interest in coal mining, and a popular pro-coal former Kentucky governor served as the lead defense counsel. The judge also suppressed as evidence the federal mine study that pointed to numerous safety violations at the Scotia mine: In a rush to produce more coal, necessary ventilation had been short-circuited, miners had not been trained in the use of self-rescue equipment, and ventilation inspections had not been made. Moreover, Scotia did not even have a trained rescue team. Ultimately, the Scotia widows’ ordeal helped to inspire the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, which changed safety regulations for coal mines throughout the country.

“The Scotia Widows” portrays in gripping detail young women deciding to pursue a landmark legal campaign against powerful corporate interests and the judge who protected them. It is a critically important and timeless story of how ordinary people “can sometimes find justice in the courtroom.”

“The Scotia Widows” is the August selection for the Jesse Stuart Foundation book group, the Regional Readers. The group will meet on August 31 in the JSF Conference Room. Coffee and conversation at 2:00 pm; book discussion begins at 2:30 pm. Participants will wear face masks and practice social distancing. The book group is open to all.

“The Scotia Widows” and other books about coal mining in Kentucky are available in the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore and Gift Shop at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, call 606.326.1667 or e-mail jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor