Before the Civil War, the Underground Railroad was a network of hundreds of safe houses, churches, and farms throughout the North and South that served as way stations on the road to freedom for tens of thousands of runaway slaves.

Fugitive slaves risked their lives in this long, hazardous journey to freedom. The whites who helped them risked social scorn, business setbacks, arrests, fines, prison and even death to lend the fugitives a helping hand. Still, by 1800, this “underground railroad,” as it gradually came to be called, was intact and operational from the deep South to Canada.

Fugitive slaves risked their lives in this long, hazardous journey to freedom. The whites who helped them risked social scorn, business setbacks, arrests, fines, prison and even death to lend the fugitives a helping hand. Still, by 1800, this “underground railroad,” as it gradually came to be called, was intact and operational from the deep South to Canada.

Because of its secretive nature, no one really knew how extensive it was. The northerners who assisted runaway slaves devised inventive hideaways for the fugitives. Many built secret rooms in their houses or barns. One abolitionist whose home was near a river dug an underground tunnel from the basement of the house to the riverbank so that slaves could flee unobserved if slavecatchers arrived.

The Underground Railroad eventually had more that 500 safe houses, and several thousand worked as conductors. Some of the safe houses belonged to the homes of very prominent citizens, but everyday folks worked on the railroad, too. Kentucky’s proximity to the the Ohio River — and to freedom for runaway slaves —prompted more activity here than in the deep South. Some leaders of this area’s underground railroad included Levi Coffin of Cincinnati, Delia Webster, a New England schoolteacher who purchased a farm in Kentucky along the Ohio River, with abolitionist funds, Calvin Fairbank, a Northern preacher who lived in Lexington, and John Rankin, who operated one of the most active stations at Ripley, Ohio.

Sometimes an entire town served as a stop. Xenia, Oberlin, and Ripley, Ohio, each had more than a dozen homes that housed fugitive slaves.

Eliza, the heroine of the novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” was based on a real woman who, chased by slave catchers, jumped onto a chunk of free-floating ice in the Ohio river and leaped from one chunk to another until she finally reached safety.

Runaways sometimes adapted creative disguises to make it to the North. One inventive light-skinned runaway couple dressed as a wealthy white couple and traveled first class on boats and trains out of the South and to freedom. One slave woman talked a young white boy into driving her wagon, pretending she was his slave, into a free state.

That combination of danger and humanity makes the Underground Railroad a great American saga. The story faded over time, but during the last few decades historical and cultural organizations have given it new life. Many homes from the Underground Railroad have been restored and turned into national landmarks, and communities have refurbished other homes and sites as educational showcases. Today, Americans can travel as individuals or with special groups to hundreds of sites with historical ties to the railroad, including two in nearby Maysville and many more in southern Ohio.

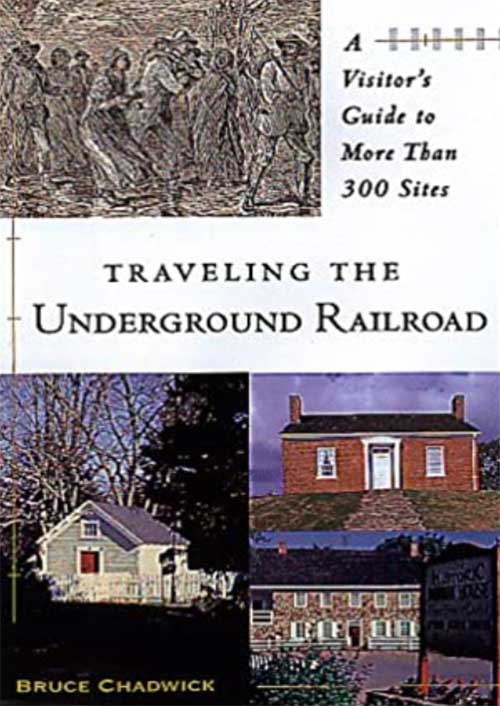

The Underground Railroad was a triumphant story of blacks and whites who worked together for freedom. If you’re interested in learning more about this fascinating part of Kentucky and American history, “Travelling The Underground Railroad,” a visitor’s guide to more than 300 sites can be purchased on this site.

This book, along with thousands of other books on Kentucky and Appalachia, is available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore, 4440 13th St. in Ashland. For more information call 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

The C.B. Nuckolls Community Center & Black History Museum has scheduled its Ashland grand opening for April 22, 2023. The museum aims to preserve Black history in Ashland with exhibits and community programs. For more information visit ashlandblackhistory.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

James M. Gifford, Ph.D. has served as the CEO & Senior Editor of the Jesse Stuart Foundation for the last 37 years. For the last three years, he and Dolores Johnson, a retired English Professor at Marshall University, have been compiling and editing a new book, “Episodes of Black Life in Central Appalachia, 1705-2022.”

Before the Civil War, the Underground Railroad was a network of hundreds of safe houses, churches, and farms throughout the North and South that served as way stations on the road to freedom for tens of thousands of runaway slaves.

Fugitive slaves risked their lives in this long, hazardous journey to freedom. The whites who helped them risked social scorn, business setbacks, arrests, fines, prison and even death to lend the fugitives a helping hand. Still, by 1800, this “underground railroad,” as it gradually came to be called, was intact and operational from the deep South to Canada.

Because of its secretive nature, no one really knew how extensive it was. The northerners who assisted runaway slaves devised inventive hideaways for the fugitives. Many built secret rooms in their houses or barns. One abolitionist whose home was near a river dug an underground tunnel from the basement of the house to the riverbank so that slaves could flee unobserved if slavecatchers arrived.

The Underground Railroad eventually had more that 500 safe houses, and several thousand worked as conductors. Some of the safe houses belonged to the homes of very prominent citizens, but everyday folks worked on the railroad, too. Kentucky’s proximity to the the Ohio River — and to freedom for runaway slaves —prompted more activity here than in the deep South. Some leaders of this area’s underground railroad included Levi Coffin of Cincinnati, Delia Webster, a New England schoolteacher who purchased a farm in Kentucky along the Ohio River, with abolitionist funds, Calvin Fairbank, a Northern preacher who lived in Lexington, and John Rankin, who operated one of the most active stations at Ripley, Ohio.

Sometimes an entire town served as a stop. Xenia, Oberlin, and Ripley, Ohio, each had more than a dozen homes that housed fugitive slaves.

Eliza, the heroine of the novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” was based on a real woman who, chased by slave catchers, jumped onto a chunk of free-floating ice in the Ohio river and leaped from one chunk to another until she finally reached safety.

Runaways sometimes adapted creative disguises to make it to the North. One inventive light-skinned runaway couple dressed as a wealthy white couple and traveled first class on boats and trains out of the South and to freedom. One slave woman talked a young white boy into driving her wagon, pretending she was his slave, into a free state.

That combination of danger and humanity makes the Underground Railroad a great American saga. The story faded over time, but during the last few decades historical and cultural organizations have given it new life. Many homes from the Underground Railroad have been restored and turned into national landmarks, and communities have refurbished other homes and sites as educational showcases. Today, Americans can travel as individuals or with special groups to hundreds of sites with historical ties to the railroad, including two in nearby Maysville and many more in southern Ohio.

The Underground Railroad was a triumphant story of blacks and whites who worked together for freedom. If you’re interested in learning more about this fascinating part of Kentucky and American history, “Travelling The Underground Railroad,” a visitor’s guide to more than 300 sites can be purchased on this site.

This book, along with thousands of other books on Kentucky and Appalachia, is available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore, 4440 13th St. in Ashland. For more information call 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

The C.B. Nuckolls Community Center & Black History Museum has scheduled its Ashland grand opening for April 22, 2023. The museum aims to preserve Black history in Ashland with exhibits and community programs. For more information visit ashlandblackhistory.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

James M. Gifford, Ph.D. has served as the CEO & Senior Editor of the Jesse Stuart Foundation for the last 37 years. For the last three years, he and Dolores Johnson, a retired English Professor at Marshall University, have been compiling and editing a new book, “Episodes of Black Life in Central Appalachia, 1705-2022.”

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor