Reviewed by Eliane Fowler Palencia ~

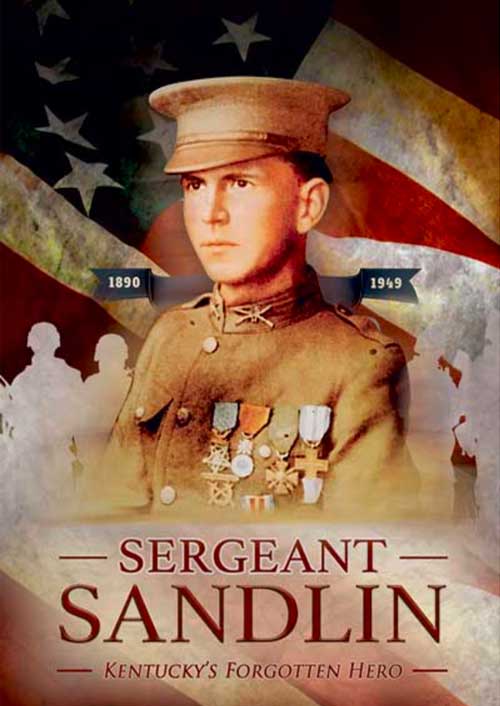

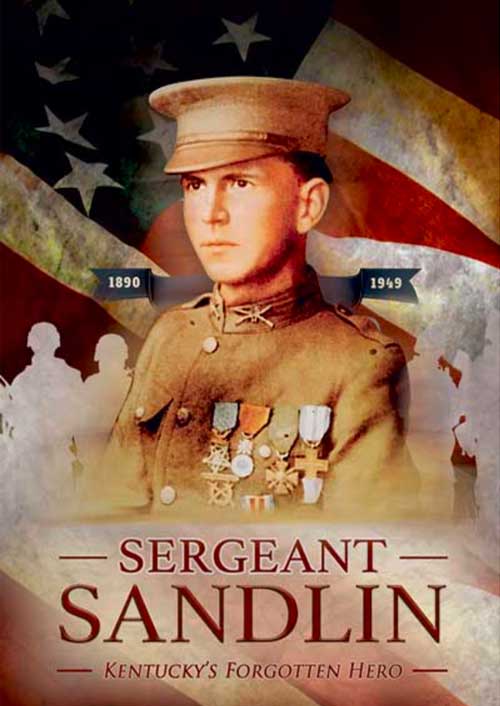

James Gifford, director of the Jesse Stuart Foundation, is always careful to set the metes and bounds of his books. Of his biography of Willie Sandlin, Kentucky’s only World War I Medal of Honor recipient, he states, “this is not a textbook, nor is it a book written for scholars. It is a popular history and inspirational biography…” (11). It is also the first biography of this modest hero, born in Breathitt County January 1, 1890, and little known today. Gifford intends for it to be a point of departure for further research and discussion.

The second of five sons born to John and Lucinda Abner Sandlin, Willie Sandlin was born into difficult circumstances and had little schooling. In 1900, when he was ten, his parents divorced. His mother died in childbirth the same year, while his father was in prison for murder. When John Sandlin was paroled in 1908, he left the county and eventually started another family. Willie and his siblings were taken in by good-hearted relatives, and he was raised in Leslie County. In 1913, at age 23, he enlisted in the Army and served along the Arizona-Mexico border under John H. Pershing. He re-enlisted in April 1917, two weeks after the United States entered World War I. He was sent to Europe, where he would again serve under Pershing, who had been named the Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces. After the War, Sandlin returned to Europe as part of a detail to identify and escort the remains of American soldiers back to the States.

The second of five sons born to John and Lucinda Abner Sandlin, Willie Sandlin was born into difficult circumstances and had little schooling. In 1900, when he was ten, his parents divorced. His mother died in childbirth the same year, while his father was in prison for murder. When John Sandlin was paroled in 1908, he left the county and eventually started another family. Willie and his siblings were taken in by good-hearted relatives, and he was raised in Leslie County. In 1913, at age 23, he enlisted in the Army and served along the Arizona-Mexico border under John H. Pershing. He re-enlisted in April 1917, two weeks after the United States entered World War I. He was sent to Europe, where he would again serve under Pershing, who had been named the Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces. After the War, Sandlin returned to Europe as part of a detail to identify and escort the remains of American soldiers back to the States.

If these facts seem bare, it is because Gifford found few written sources connected directly to Sandlin—”only two letters and one postcard written by him” (11). Gifford points readers to David J. Bettez’ Kentucky and the Great War: World War I on the Home Front for the range of thoughts and feelings among the citizenry on the eve of the conflict, as well as for the bureaucratic preparations. He found plenty of official and journalistic documentation of Sandlin’s greatest act of courage, which occurred during the Battle of the Argonne Forest.

On September 26, 1918, at Bois de Forges, Sergeant Sandlin and his platoon were unable to advance due to German machine gun fire. Armed with an automatic pistol, a rifle, and four hand grenades, he charged the machine gun nests alone. Those Germans in the first emplacement who survived his grenades, Sandlin bayonetted. As his troops advanced, he took out two more machine gun nests. In all he killed 24 enemy soldiers and made possible the capture of two hundred others. (56). He also suffered shrapnel wounds. For these acts, he was given the Medal of Honor by General Perching himself, who “would later describe Sandlin as the outstanding regular army soldier of World War I” (54).

Sandlin’s heroics beg comparison with another Medal of Honor winner from the Argonne Forest campaign, Sergeant Alvin York of Tennessee. Gifford usefully juxtaposes the lives of these two central Appalachian men. Of similar cultural backgrounds, both took on the enemy alone in a tide-turning moment, then came back to their home counties to raise large families and do good works. But there were differences. York embraced fame, feeling it would bring support for his charitable initiatives. Sandlin went into “purposeful obscurity” (14) and refused to profit from his celebrity. Here one wishes for more information on Sandlin’s motives. Why did he enlist in the military at 23? What effect did his actions and the horrors of trench warfare have on him? Gifford interviewed Sandlin’s surviving children and relatives, who supplied concrete memories of Sandlin’s post-war life and his kind, hard-working personality. Perhaps because this is an “inspirational” project, the psychological effect of the war is not explored; and indeed, trauma-informed understanding of the common soldier hardly existed for World War I. Sandlin was known not to speak of his service if he could avoid it. Robert Graves’ memoir of the horrors he experienced in the same war, Goodbye to All That, can offer context.

A fair assumption can be made that Sandlin’s efforts to improve the lot of Kentuckians stemmed, at least in part, from witnessing the destruction of war. For example, he joined the literacy campaign of Morehead’s Cora Wilson Stewart, traveling with her to speak all over the state. Although Sandlin’s family disputed Stewart’s claim that he could barely read and write until he came under her tutelage, he did turn down Army commissions more than once, pleading lack of education. Eradicating illiteracy among draft-age young men was an emphasis of Stewart’s. She wrote Soldier’s First Book (1918), a short reader (in the possession of this reviewer) whose lessons also teach patriotic and family values. Lesson 3, for example, offers these sentences to learn: “See the flag! It is our flag. Our flag never knew defeat. Why? Our flag has always stood for right.” This literacy project was one that Sandlin could get behind. He and his wife Belvia became friends with Stewart and named a daughter for her. See Yvonne Hunnicutt Baldwin’s Cora Wilson Stewart and Kentucky’s Moonlight Schools: Fight for Literacy in America, for the breadth of that enterprise. The Sandlins also supported the Frontier Nursing Service and worked with Mary Carson Breckinridge, its founder, to bring medical services to remote areas of Eastern Kentucky. Breckinridge refers fondly to Sandlin in her autobiography, Wide Neighborhoods: The Story of the Frontier Nursing Service.

Sandlin’s post-war life differed from Sergeant York’s in another important way. York returned physically sound. But on October 9, two weeks after charging the machine gun nests, Sandlin was gassed in the Argonne Forest. Directed to a field hospital, he refused to leave his unit. This decision would have far-reaching consequences, which Gifford explores in detail. For the rest of his life, Sandlin suffered from lung problems, finally dying at 59 of pulmonary emphysema and cardiovascular disease, having suffered seizures toward the end. Because he did not seek medical attention immediately, the Army had no record of the lung damage. Sandlin spent decades trying to get compensation for this war-related disability while working at WPA jobs and subsistence farming. A daughter recalled his sitting up all night with his back against the warm chimney to ease his breathing (117). Still, at 52, he tried to re-enlist during World War II, as did York. Both were turned down for age and health reasons. Between the federal bureaucracy and the strangely tangled efforts of the VFW to raise funds for this war hero, the family saw almost nothing of the money that should have come to them. But Sandlin remained intensely loyal both to his country and to his region, staying active in the VFW and the American Legion.

The book is lavishly illustrated with photos, both black-and-white and color; personal and official documents; pictures of military medals; and recruitment posters. A chronology of Sandlin’s life is included, as well as a list of all the Medal of Honor recipients from Kentucky. Appendix A gives explanations for each of the medals Sandlin received, foreign and domestic. There are endnotes and a name index, but no bibliography.

In December 1941, the journalist John F. Day visited the Sandlin family. Day was from Eastern Kentucky and had just published Bloody Ground, his grim and still disturbing portrait of the region’s people, which gives a different picture than this one of the area. Gifford quotes liberally from the sympathetic interview Day subsequently published in the December 24 Pittsburg (PA) Post-Gazette under the headline, “Hero Prefers the Hills.” “You never heard of Willie Sandlin?” Day begins before describing how Sandlin, though cordial, deflected talk of his heroism during Day’s visit and turned to jokes when Belvia brough out his medals. To many, Sandlin is still unknown. But besides the welcome corrective of this biography, Gifford’s efforts have produced at least one other notable result. Before publishing this book, Gifford published a sketch of Sandlin’s life in the Fall 2017 Kentucky Humanities Magazine. On April 9, 2018, Senator Mitch McConnell had the article entered in the Congressional Record (vol. 164, no. 186).

Elaine Palencia, who lives in Champaign, IL, is from Eastern Kentucky. In Fall 2020, Mercer University Press published her book about her maternal great-great grandfather, On Rising Ground: The Life and Civil War letters of John M. Douthit, 52nd Georgia Volunteer Infantry, CSA, an Appalachian soldier from a different war.

Reviewed by Eliane Fowler Palencia ~

James Gifford, director of the Jesse Stuart Foundation, is always careful to set the metes and bounds of his books. Of his biography of Willie Sandlin, Kentucky’s only World War I Medal of Honor recipient, he states, “this is not a textbook, nor is it a book written for scholars. It is a popular history and inspirational biography…” (11). It is also the first biography of this modest hero, born in Breathitt County January 1, 1890, and little known today. Gifford intends for it to be a point of departure for further research and discussion.

The second of five sons born to John and Lucinda Abner Sandlin, Willie Sandlin was born into difficult circumstances and had little schooling. In 1900, when he was ten, his parents divorced. His mother died in childbirth the same year, while his father was in prison for murder. When John Sandlin was paroled in 1908, he left the county and eventually started another family. Willie and his siblings were taken in by good-hearted relatives, and he was raised in Leslie County. In 1913, at age 23, he enlisted in the Army and served along the Arizona-Mexico border under John H. Pershing. He re-enlisted in April 1917, two weeks after the United States entered World War I. He was sent to Europe, where he would again serve under Pershing, who had been named the Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces. After the War, Sandlin returned to Europe as part of a detail to identify and escort the remains of American soldiers back to the States.

If these facts seem bare, it is because Gifford found few written sources connected directly to Sandlin—”only two letters and one postcard written by him” (11). Gifford points readers to David J. Bettez’ Kentucky and the Great War: World War I on the Home Front for the range of thoughts and feelings among the citizenry on the eve of the conflict, as well as for the bureaucratic preparations. He found plenty of official and journalistic documentation of Sandlin’s greatest act of courage, which occurred during the Battle of the Argonne Forest.

On September 26, 1918, at Bois de Forges, Sergeant Sandlin and his platoon were unable to advance due to German machine gun fire. Armed with an automatic pistol, a rifle, and four hand grenades, he charged the machine gun nests alone. Those Germans in the first emplacement who survived his grenades, Sandlin bayonetted. As his troops advanced, he took out two more machine gun nests. In all he killed 24 enemy soldiers and made possible the capture of two hundred others. (56). He also suffered shrapnel wounds. For these acts, he was given the Medal of Honor by General Perching himself, who “would later describe Sandlin as the outstanding regular army soldier of World War I” (54).

Sandlin’s heroics beg comparison with another Medal of Honor winner from the Argonne Forest campaign, Sergeant Alvin York of Tennessee. Gifford usefully juxtaposes the lives of these two central Appalachian men. Of similar cultural backgrounds, both took on the enemy alone in a tide-turning moment, then came back to their home counties to raise large families and do good works. But there were differences. York embraced fame, feeling it would bring support for his charitable initiatives. Sandlin went into “purposeful obscurity” (14) and refused to profit from his celebrity. Here one wishes for more information on Sandlin’s motives. Why did he enlist in the military at 23? What effect did his actions and the horrors of trench warfare have on him? Gifford interviewed Sandlin’s surviving children and relatives, who supplied concrete memories of Sandlin’s post-war life and his kind, hard-working personality. Perhaps because this is an “inspirational” project, the psychological effect of the war is not explored; and indeed, trauma-informed understanding of the common soldier hardly existed for World War I. Sandlin was known not to speak of his service if he could avoid it. Robert Graves’ memoir of the horrors he experienced in the same war, Goodbye to All That, can offer context.

A fair assumption can be made that Sandlin’s efforts to improve the lot of Kentuckians stemmed, at least in part, from witnessing the destruction of war. For example, he joined the literacy campaign of Morehead’s Cora Wilson Stewart, traveling with her to speak all over the state. Although Sandlin’s family disputed Stewart’s claim that he could barely read and write until he came under her tutelage, he did turn down Army commissions more than once, pleading lack of education. Eradicating illiteracy among draft-age young men was an emphasis of Stewart’s. She wrote Soldier’s First Book (1918), a short reader (in the possession of this reviewer) whose lessons also teach patriotic and family values. Lesson 3, for example, offers these sentences to learn: “See the flag! It is our flag. Our flag never knew defeat. Why? Our flag has always stood for right.” This literacy project was one that Sandlin could get behind. He and his wife Belvia became friends with Stewart and named a daughter for her. See Yvonne Hunnicutt Baldwin’s Cora Wilson Stewart and Kentucky’s Moonlight Schools: Fight for Literacy in America, for the breadth of that enterprise. The Sandlins also supported the Frontier Nursing Service and worked with Mary Carson Breckinridge, its founder, to bring medical services to remote areas of Eastern Kentucky. Breckinridge refers fondly to Sandlin in her autobiography, Wide Neighborhoods: The Story of the Frontier Nursing Service.

Sandlin’s post-war life differed from Sergeant York’s in another important way. York returned physically sound. But on October 9, two weeks after charging the machine gun nests, Sandlin was gassed in the Argonne Forest. Directed to a field hospital, he refused to leave his unit. This decision would have far-reaching consequences, which Gifford explores in detail. For the rest of his life, Sandlin suffered from lung problems, finally dying at 59 of pulmonary emphysema and cardiovascular disease, having suffered seizures toward the end. Because he did not seek medical attention immediately, the Army had no record of the lung damage. Sandlin spent decades trying to get compensation for this war-related disability while working at WPA jobs and subsistence farming. A daughter recalled his sitting up all night with his back against the warm chimney to ease his breathing (117). Still, at 52, he tried to re-enlist during World War II, as did York. Both were turned down for age and health reasons. Between the federal bureaucracy and the strangely tangled efforts of the VFW to raise funds for this war hero, the family saw almost nothing of the money that should have come to them. But Sandlin remained intensely loyal both to his country and to his region, staying active in the VFW and the American Legion.

The book is lavishly illustrated with photos, both black-and-white and color; personal and official documents; pictures of military medals; and recruitment posters. A chronology of Sandlin’s life is included, as well as a list of all the Medal of Honor recipients from Kentucky. Appendix A gives explanations for each of the medals Sandlin received, foreign and domestic. There are endnotes and a name index, but no bibliography.

In December 1941, the journalist John F. Day visited the Sandlin family. Day was from Eastern Kentucky and had just published Bloody Ground, his grim and still disturbing portrait of the region’s people, which gives a different picture than this one of the area. Gifford quotes liberally from the sympathetic interview Day subsequently published in the December 24 Pittsburg (PA) Post-Gazette under the headline, “Hero Prefers the Hills.” “You never heard of Willie Sandlin?” Day begins before describing how Sandlin, though cordial, deflected talk of his heroism during Day’s visit and turned to jokes when Belvia brough out his medals. To many, Sandlin is still unknown. But besides the welcome corrective of this biography, Gifford’s efforts have produced at least one other notable result. Before publishing this book, Gifford published a sketch of Sandlin’s life in the Fall 2017 Kentucky Humanities Magazine. On April 9, 2018, Senator Mitch McConnell had the article entered in the Congressional Record (vol. 164, no. 186).

Elaine Palencia, who lives in Champaign, IL, is from Eastern Kentucky. In Fall 2020, Mercer University Press published her book about her maternal great-great grandfather, On Rising Ground: The Life and Civil War letters of John M. Douthit, 52nd Georgia Volunteer Infantry, CSA, an Appalachian soldier from a different war.