Reviewed by Elaine Fowler Palencia ~

More than 30 years have passed since the winds generated by Jesse Hilton Stuart’s astonishing energy blew through eastern Kentucky. The experiences of subsistence farming and teaching in one-room schools that he drew on to become “America’s most famous chronicler of rural life” (9), are mostly gone. The way of life that molded Stuart, the son of uneducated tenant farmers, is as unknown to young people today as that of Little House on the Prairie. We live in a different world, but one that can still benefit from knowing his life and work. Fortunately, five years before his death in 1984, Stuart—author, educator, cultural ambassador, farmer, conservationist, and more—established the Jesse Stuart Foundation to preserve his legacy.

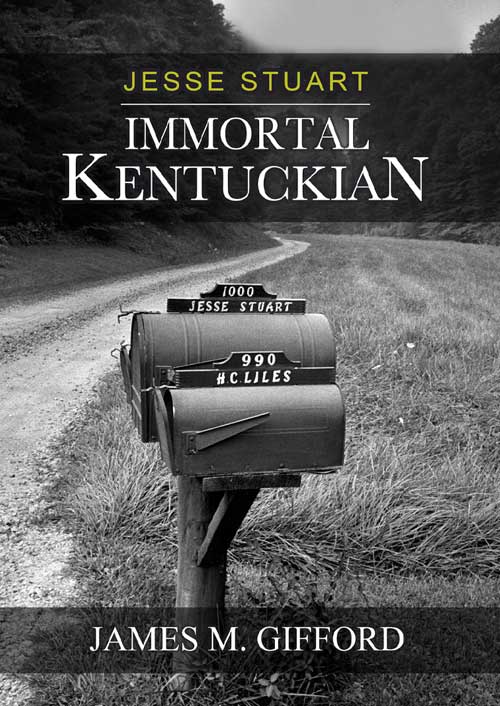

In 2010, Dr. James Gifford, longtime executive director of the foundation, published, with Erin R. Kazee, Jesse Stuart: An Extraordinary Life. But with an unmatched archive at his disposal, including over 20,000 letters to and from Stuart, Gifford felt there was more to say. This new biography, structured differently from the earlier, topically organized book and containing new material, embeds a chronological account of Stuart’s life within a context that brings alive the eastern Kentucky of his time and encompasses sketches of people who have kept his memory alive. Gifford sees this new book as an “intellectual extension” of the earlier one and more suitable for students (13). Kazee and Edwina Pendarvis were involved in the project early on, but left for different reasons while Gifford worked on for four years to bring this book to completion.

In 2010, Dr. James Gifford, longtime executive director of the foundation, published, with Erin R. Kazee, Jesse Stuart: An Extraordinary Life. But with an unmatched archive at his disposal, including over 20,000 letters to and from Stuart, Gifford felt there was more to say. This new biography, structured differently from the earlier, topically organized book and containing new material, embeds a chronological account of Stuart’s life within a context that brings alive the eastern Kentucky of his time and encompasses sketches of people who have kept his memory alive. Gifford sees this new book as an “intellectual extension” of the earlier one and more suitable for students (13). Kazee and Edwina Pendarvis were involved in the project early on, but left for different reasons while Gifford worked on for four years to bring this book to completion.

Gifford is clear in his intention to write neither a literary analysis of Stuart’s works nor a hagiography. What he does is to reveal the man behind the self-created myth, often through Stuart’s correspondence. We see the tremendous influence Stuart’s teaching and writing had on the articulation of an Appalachian sensibility based on hard work, family, land, and respect for education. We hear from students he helped send to college or get jobs and of others inspired to be teachers by works like The Thread That Runs So True, Stuart’s 1949 account of 20 years as a teacher and school administrator. But we also read of his early womanizing and view of women. (“Women were numbers: from his mother to his girlfriends, they were spoken of in terms of their height, weight, and the number of miles Jesse traveled to see them” [172]), and of the fractious spirit behind his political and personal dustups. “I like my friends and I hate my enemies. Goddamn an enemy. Christ said when one was not with him he was against him. I can’t be any other way,” he declared in a letter to editor Merton S. Yewdale (134). Gifford gently distinguishes between being a wonderful storyteller, which Stuart was, and being an excellent writer, which he sometimes did not take enough pains to be. Indeed, his output was so prodigious that he could not have weighed his words, except in bulk. Stuart was sensitive to this charge but was driven to publish some 2,000 poems, 460 short stories, and more than 60 books (9).

Still, this book primarily tells a story shaped by the subject himself. It could hardly be otherwise, given the autobiographical nature of Stuart’s oeuvre. For example, many details of Stuart’s early life and education come from the autobiographical Beyond Dark Hills. One wonders at times if Stuart’s version of events is true. Would a natural storyteller, bent on achieving immortality, have let facts stand in the way of a good story? Nevertheless, Gifford goes a long way towards furnishing tales untold by earlier biographers, giving a rounder picture of events.

To be sure, Stuart’s is a powerful story and one that he never tired of telling in fiction, poetry, autobiography, and speeches, recognizing his life as a quintessentially America story that many would identify with and admire. Of particular interest here is his unconventionally informal 1937 application letter to the Guggenheim Foundation, which awarded him funds to study in Scotland. The tone is naïve; but one feels that Stuart knew he would stand out among more affluent students for having written poetry “all the time I was in the mills where there were clouds of smoke by day and pillars of fire by night. Believe it or not I made a good blacksmith. I could temper steel pretty well…” (142).

The correspondence between Stuart and two Lincoln Memorial University classmates who also achieved renown, James Still and Don West, reveals the mercurial changes a friend of Jesse might have to endure. Stuart could compliment Still on his own writing: “It looks to me like you are on top of the world. I feel proud that you are doing what you are a-doing,” he wrote in 1935 (111). But he could also denigrate Still out of jealousy, telling a researcher, “I thought of [Still] as being a very odd person, never too friendly…I tried for all the literary prizes that LMU offered and never won any. Still won these” (84). Stuart and West fell out over politics and money, sparring in letters and articles. Each gave as good as he got before reconciling in later years.

A writer dedicated to transforming the local into the universal, Stuart always returned to W-Hollow, where he grew up and where he made his home with his wife Naomi and their daughter. Local people occupy a large and neighborly place in this telling. The chapter about Jesse’s World War II military service, for instance, includes the tale of four hometown women who served in Washington. Details from The W-Hollow Cookbook, compiled by Jessie’s sister Glennis—hog killing, herb gathering, food preservation—enhance the description of his origins and are reminiscent of Verna Mae Slone’s books about Knott County.

Writing with the familiarity of a clear-eyed neighbor himself, Gifford captures the red-blooded, passionate, talented man. Though not an exposé, the book does serve as a corrective to the worshipful view of Stuart taken by some writers. Yet the many well-chosen excerpts from Stuart’s letters demonstrate his vitality and charisma as well. The book focuses on personal connections to the point that only people’s names are indexed, making it difficult to use the book as a research tool. Many photos are included. The profiles, interesting mainly to Stuart industry insiders, increasingly take over the book. However, it does what a good biography should do: send the reader back to Stuart’s writings. Further, it captures the “spirit of the one-room schoolhouse” (312), the personal philosophy of education that Stuart spent a lifetime promoting. A genealogical outline is appended, as well as Merton S. Yewdale’s 1934 editorial assessment of Stuart’s 703-sonnet cycle, Man with a Bull-Tongue Plow, for E.P. Dutton & Company, calling it “one of the greatest poetical works that ever came out of America” (344) and prophetic in its recognition of the future influence of Jesse Stuart.

Elaine Fowler Palencia grew up in Morehead, Kentucky, where she used to see Jesse and Naomi Stuart eating at the Eagles Nest Restaurant. She is the author of two collections of Appalachian fiction and three poetry chapbooks, including Going Places.

“Jesse Stuart: Immortal Kentuckian,” Appalachian Journal (Spring/Summer, 2016), 273-276.

Reviewed by Elaine Fowler Palencia ~

More than 30 years have passed since the winds generated by Jesse Hilton Stuart’s astonishing energy blew through eastern Kentucky. The experiences of subsistence farming and teaching in one-room schools that he drew on to become “America’s most famous chronicler of rural life” (9), are mostly gone. The way of life that molded Stuart, the son of uneducated tenant farmers, is as unknown to young people today as that of Little House on the Prairie. We live in a different world, but one that can still benefit from knowing his life and work. Fortunately, five years before his death in 1984, Stuart—author, educator, cultural ambassador, farmer, conservationist, and more—established the Jesse Stuart Foundation to preserve his legacy.

In 2010, Dr. James Gifford, longtime executive director of the foundation, published, with Erin R. Kazee, Jesse Stuart: An Extraordinary Life. But with an unmatched archive at his disposal, including over 20,000 letters to and from Stuart, Gifford felt there was more to say. This new biography, structured differently from the earlier, topically organized book and containing new material, embeds a chronological account of Stuart’s life within a context that brings alive the eastern Kentucky of his time and encompasses sketches of people who have kept his memory alive. Gifford sees this new book as an “intellectual extension” of the earlier one and more suitable for students (13). Kazee and Edwina Pendarvis were involved in the project early on, but left for different reasons while Gifford worked on for four years to bring this book to completion.

Gifford is clear in his intention to write neither a literary analysis of Stuart’s works nor a hagiography. What he does is to reveal the man behind the self-created myth, often through Stuart’s correspondence. We see the tremendous influence Stuart’s teaching and writing had on the articulation of an Appalachian sensibility based on hard work, family, land, and respect for education. We hear from students he helped send to college or get jobs and of others inspired to be teachers by works like The Thread That Runs So True, Stuart’s 1949 account of 20 years as a teacher and school administrator. But we also read of his early womanizing and view of women. (“Women were numbers: from his mother to his girlfriends, they were spoken of in terms of their height, weight, and the number of miles Jesse traveled to see them” [172]), and of the fractious spirit behind his political and personal dustups. “I like my friends and I hate my enemies. Goddamn an enemy. Christ said when one was not with him he was against him. I can’t be any other way,” he declared in a letter to editor Merton S. Yewdale (134). Gifford gently distinguishes between being a wonderful storyteller, which Stuart was, and being an excellent writer, which he sometimes did not take enough pains to be. Indeed, his output was so prodigious that he could not have weighed his words, except in bulk. Stuart was sensitive to this charge but was driven to publish some 2,000 poems, 460 short stories, and more than 60 books (9).

Still, this book primarily tells a story shaped by the subject himself. It could hardly be otherwise, given the autobiographical nature of Stuart’s oeuvre. For example, many details of Stuart’s early life and education come from the autobiographical Beyond Dark Hills. One wonders at times if Stuart’s version of events is true. Would a natural storyteller, bent on achieving immortality, have let facts stand in the way of a good story? Nevertheless, Gifford goes a long way towards furnishing tales untold by earlier biographers, giving a rounder picture of events.

To be sure, Stuart’s is a powerful story and one that he never tired of telling in fiction, poetry, autobiography, and speeches, recognizing his life as a quintessentially America story that many would identify with and admire. Of particular interest here is his unconventionally informal 1937 application letter to the Guggenheim Foundation, which awarded him funds to study in Scotland. The tone is naïve; but one feels that Stuart knew he would stand out among more affluent students for having written poetry “all the time I was in the mills where there were clouds of smoke by day and pillars of fire by night. Believe it or not I made a good blacksmith. I could temper steel pretty well…” (142).

The correspondence between Stuart and two Lincoln Memorial University classmates who also achieved renown, James Still and Don West, reveals the mercurial changes a friend of Jesse might have to endure. Stuart could compliment Still on his own writing: “It looks to me like you are on top of the world. I feel proud that you are doing what you are a-doing,” he wrote in 1935 (111). But he could also denigrate Still out of jealousy, telling a researcher, “I thought of [Still] as being a very odd person, never too friendly…I tried for all the literary prizes that LMU offered and never won any. Still won these” (84). Stuart and West fell out over politics and money, sparring in letters and articles. Each gave as good as he got before reconciling in later years.

A writer dedicated to transforming the local into the universal, Stuart always returned to W-Hollow, where he grew up and where he made his home with his wife Naomi and their daughter. Local people occupy a large and neighborly place in this telling. The chapter about Jesse’s World War II military service, for instance, includes the tale of four hometown women who served in Washington. Details from The W-Hollow Cookbook, compiled by Jessie’s sister Glennis—hog killing, herb gathering, food preservation—enhance the description of his origins and are reminiscent of Verna Mae Slone’s books about Knott County.

Writing with the familiarity of a clear-eyed neighbor himself, Gifford captures the red-blooded, passionate, talented man. Though not an exposé, the book does serve as a corrective to the worshipful view of Stuart taken by some writers. Yet the many well-chosen excerpts from Stuart’s letters demonstrate his vitality and charisma as well. The book focuses on personal connections to the point that only people’s names are indexed, making it difficult to use the book as a research tool. Many photos are included. The profiles, interesting mainly to Stuart industry insiders, increasingly take over the book. However, it does what a good biography should do: send the reader back to Stuart’s writings. Further, it captures the “spirit of the one-room schoolhouse” (312), the personal philosophy of education that Stuart spent a lifetime promoting. A genealogical outline is appended, as well as Merton S. Yewdale’s 1934 editorial assessment of Stuart’s 703-sonnet cycle, Man with a Bull-Tongue Plow, for E.P. Dutton & Company, calling it “one of the greatest poetical works that ever came out of America” (344) and prophetic in its recognition of the future influence of Jesse Stuart.

Elaine Fowler Palencia grew up in Morehead, Kentucky, where she used to see Jesse and Naomi Stuart eating at the Eagles Nest Restaurant. She is the author of two collections of Appalachian fiction and three poetry chapbooks, including Going Places.

“Jesse Stuart: Immortal Kentuckian,” Appalachian Journal (Spring/Summer, 2016), 273-276.