From colonial beginnings until early in the twentieth century, one-room schools played an important role in Eastern Kentucky education. These tiny schools that dotted the hills and valleys were, collectively, a salvation to a region recovering from the Civil War and, later, the Great Depression. In the nineteenth century, makeshift schools were located within walking distance of a few families who could pay the teacher. By the early twentieth century, little had changed except that the teacher was paid by county and state governments. Kentucky had 7,067 one-room schools in operation in the 1918-1919 school years.

Between the end of the Civil War and 1930, rural people often cleared less than one hundred dollars per year for their back-breaking work on farms or in mines. To them, education was a luxury they could not afford. Though disinterested in many national economic issues, they bitterly opposed local property taxation to support education. Consequently, many barns and most county jails in Eastern Kentucky were in better repair and more comfortable than the dusty, wasp-infested little schools where thousands of barefoot children studied without benefit of maps, globes, or other educational aides.

Between the end of the Civil War and 1930, rural people often cleared less than one hundred dollars per year for their back-breaking work on farms or in mines. To them, education was a luxury they could not afford. Though disinterested in many national economic issues, they bitterly opposed local property taxation to support education. Consequently, many barns and most county jails in Eastern Kentucky were in better repair and more comfortable than the dusty, wasp-infested little schools where thousands of barefoot children studied without benefit of maps, globes, or other educational aides.

A “trustee” administered the one-room in his district. A large percentage of these trustees could neither read nor write and were subordinate to thousands of state officials who were also illiterate. The system was highly politicized, often corrupt, and usually inadequate.

What these schools lacked in modern conveniences and competent management, they overcame with students motivated to endure hardships in order to learn and teachers willing to work under difficult circumstances to achieve progress. These forgotten heroes and heroines did not, according to one former teacher, “give poverty a chance to impede their love of learning.”

To maintain appropriate school conduct, some teachers had a lengthy catalog of rules, which specified a punishment for each infraction. A teacher had to maintain credibility as a disciplinarian. If students knew they would be punished, they rarely misbehaved; and parents tended to be tolerant and supportive of the teacher’s decisions.

Transportation to and from school, by today’s standards, ranked somewhere between inconvenient and impossible. The school building itself was of wooden frame construction. It typically had a front door that faced the road or path, three windows on each side of the building, and a painted blackboard across the back. Outside there was often a well, a coal house, and two outdoor toilets. Two long recitation benches faced the teacher’s desk and blackboard. Rows of desks or benches, a “warm-morning” stove, and a water bucket completed the list of basic equipment.

Successful one-room teachers usually made good use of the skills and interests of older students, who often helped the younger children with their lessons. For many of these students, the additional responsibility was a good learning experience.

By the mid-1900s, the remaining one-room school buildings were in terrible repair and the system was considered old-fashioned by most educators, yet many were still in use. In 1956, the Louisville Courier-Journal Magazine reported that of 35 one-room schools in Greenup County, Kentucky, 34 had defective toilet facilities and no hand-washing facilities, 33 had an inadequate water supply, and 32 had faulty heating and ventilation and were housed in bad buildings. The push for school consolidation was as much about the physical state of the schools as it was the need for a “more modern” curriculum.

Almost without exception, though, former one-room schoolteachers report happy memories of their teaching days and personal pride in their accomplishments. Although teaching as many as eight different grades each day was hard, the teacher did not feel that the students learned less. Some of these former teachers even say that the old ways were preferable, claiming that one-room school education produced students with more creativity and greater self-reliance.

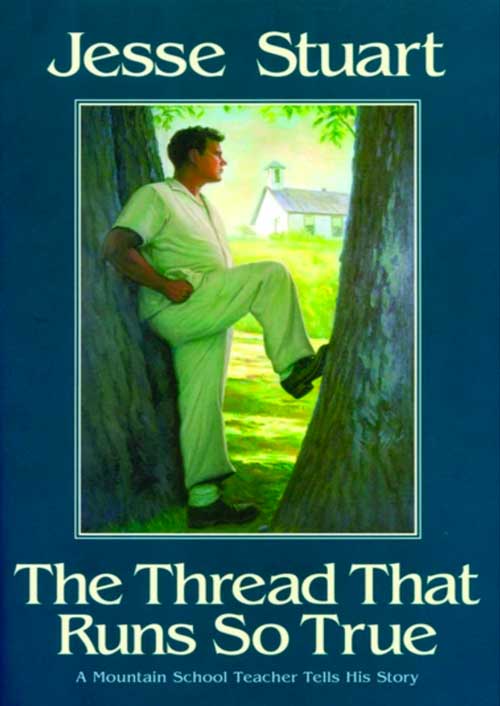

If you are interested in reading more about one-room school life, I recommend “The Thread That Runs So True” and “To Teach, To Love” by Jesse Stuart; “I Become A Teacher” by Cratis Williams; “Miss Willie” by Janice Holt Giles, and “Forty Years In The One-Room Schools Of Eastern Kentucky” by Curt Davis. For more information, call the Jesse Stuart Foundation at 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

From colonial beginnings until early in the twentieth century, one-room schools played an important role in Eastern Kentucky education. These tiny schools that dotted the hills and valleys were, collectively, a salvation to a region recovering from the Civil War and, later, the Great Depression. In the nineteenth century, makeshift schools were located within walking distance of a few families who could pay the teacher. By the early twentieth century, little had changed except that the teacher was paid by county and state governments. Kentucky had 7,067 one-room schools in operation in the 1918-1919 school years.

Between the end of the Civil War and 1930, rural people often cleared less than one hundred dollars per year for their back-breaking work on farms or in mines. To them, education was a luxury they could not afford. Though disinterested in many national economic issues, they bitterly opposed local property taxation to support education. Consequently, many barns and most county jails in Eastern Kentucky were in better repair and more comfortable than the dusty, wasp-infested little schools where thousands of barefoot children studied without benefit of maps, globes, or other educational aides.

A “trustee” administered the one-room in his district. A large percentage of these trustees could neither read nor write and were subordinate to thousands of state officials who were also illiterate. The system was highly politicized, often corrupt, and usually inadequate.

What these schools lacked in modern conveniences and competent management, they overcame with students motivated to endure hardships in order to learn and teachers willing to work under difficult circumstances to achieve progress. These forgotten heroes and heroines did not, according to one former teacher, “give poverty a chance to impede their love of learning.”

To maintain appropriate school conduct, some teachers had a lengthy catalog of rules, which specified a punishment for each infraction. A teacher had to maintain credibility as a disciplinarian. If students knew they would be punished, they rarely misbehaved; and parents tended to be tolerant and supportive of the teacher’s decisions.

Transportation to and from school, by today’s standards, ranked somewhere between inconvenient and impossible. The school building itself was of wooden frame construction. It typically had a front door that faced the road or path, three windows on each side of the building, and a painted blackboard across the back. Outside there was often a well, a coal house, and two outdoor toilets. Two long recitation benches faced the teacher’s desk and blackboard. Rows of desks or benches, a “warm-morning” stove, and a water bucket completed the list of basic equipment.

Successful one-room teachers usually made good use of the skills and interests of older students, who often helped the younger children with their lessons. For many of these students, the additional responsibility was a good learning experience.

By the mid-1900s, the remaining one-room school buildings were in terrible repair and the system was considered old-fashioned by most educators, yet many were still in use. In 1956, the Louisville Courier-Journal Magazine reported that of 35 one-room schools in Greenup County, Kentucky, 34 had defective toilet facilities and no hand-washing facilities, 33 had an inadequate water supply, and 32 had faulty heating and ventilation and were housed in bad buildings. The push for school consolidation was as much about the physical state of the schools as it was the need for a “more modern” curriculum.

Almost without exception, though, former one-room schoolteachers report happy memories of their teaching days and personal pride in their accomplishments. Although teaching as many as eight different grades each day was hard, the teacher did not feel that the students learned less. Some of these former teachers even say that the old ways were preferable, claiming that one-room school education produced students with more creativity and greater self-reliance.

If you are interested in reading more about one-room school life, I recommend “The Thread That Runs So True” and “To Teach, To Love” by Jesse Stuart; “I Become A Teacher” by Cratis Williams; “Miss Willie” by Janice Holt Giles, and “Forty Years In The One-Room Schools Of Eastern Kentucky” by Curt Davis. For more information, call the Jesse Stuart Foundation at 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor