Several years ago, as my tribute to Veterans’ Day, I wrote about Willie Sandlin, Kentucky’s only World War I Medal of Honor recipient. Last year, I wrote a lengthy essay, “In Praise of Appalachian Soldiers,” which was serialized in the Daily Independent. This year, I am writing about Jesse Stuart’s service during World War II. In the process of writing about a local sailor, I hope to honor every other man and woman who has served in America’s armed forces.

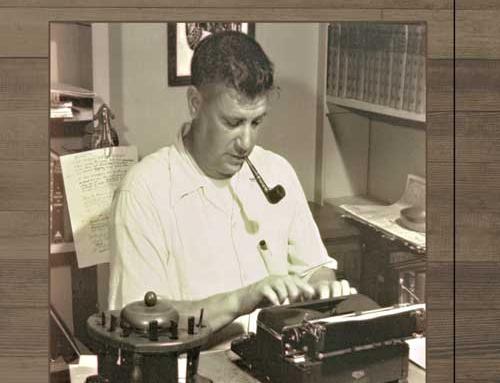

In 1942, Jesse Stuart tried to enlist in the Army and failed the physical exam. Two years later, Jesse tried to enter the war again by joining the Navy. This time, he passed his physical exam in Huntington, West Virginia, in February, and was sworn in at Louisville on March 31, 1944. He left immediately for basic training at the Great Lakes Training Command near Chicago and was there for fourteen weeks, missing his family, and their “little home, dogs and chickens.”

On July 12, 1944, a month before his thirty-eighth birthday, he graduated and was commissioned as a lieutenant (j.g.). He was assigned to the Bureau of Aeronautics in Washington, D.C., where he worked until the war ended. In the Writers Unit, he was given weak assignments that did not stimulate his cyclonic energy.

On July 12, 1944, a month before his thirty-eighth birthday, he graduated and was commissioned as a lieutenant (j.g.). He was assigned to the Bureau of Aeronautics in Washington, D.C., where he worked until the war ended. In the Writers Unit, he was given weak assignments that did not stimulate his cyclonic energy.

Jesse was conflicted over his role in the war. He felt guilty because of the “easy life” he and his co-workers were living in Washington and wondered if he could have been more useful as a farmer than as a bureaucrat in uniform. Meanwhile, his younger brother, James, was in the Leyte, Luzon, and Okinawa invasions.

As with most American families, World War II was a family affair for the Stuarts. While Jesse and James joined two million fellow southerners in uniform, their three sisters worked at the Clayton Lambert munitions plant in Wurtland (Greenup County) during the war. Sophia, Mary, and Glennis were part of a generation of American women who proved that “the woman’s place” was not necessarily in the home. In the national workplace, women replaced men who were serving during World War II and women also, for the first time in American history, served in non-combat jobs in the armed services. More than 250,000 women served as Wacs (Army), Spars (Coast Guard), Waves (Navy), and in the Marine Corps. The “girls behind the men behind the guns” were machinists, storekeepers, clerical workers, and radio operators, and they drove jeeps and trucks and flew airplanes in non-combat roles. During the 1940s, they played an active role in winning a two-front war that spanned the entire globe.

Jesse Stuart was mustered out of the Navy on December 31, 1945. He and his family left Washington “in a hurry” to get home. They departed at noon in poor driving conditions and drove seven and a half hours to Clarksburg, West Virginia, a distance of almost 250 miles.The next day they weathered a “blinding snowstorm and icy roads” to Ohio, where conditions improved for the remainder of the trip. They stayed in Greenup with his wife’s parents for two days, waiting for the ground to freeze so they could drive the rutted dirt roads into their beloved W-Hollow.

More than a decade later, he observed that for “one year after I got out of the service all I wrote should have been burned. What was wrong? You tell me. I don’t know.”

Similarly, after World War II, the great Kentucky writer James Still sat “for months … in the door of [his] log house and could not arouse interest in things [he] had done before.” He eventually began to write again, but his pace was slower, more deliberate–all in all, less enthusiastic. The war had left him a “changed man.” Jesse suffered the same postwar malaise, complaining in 1946 that he didn’t “have any book coming out or any ideas.”

Stuart, Still, and millions of other soldiers suffered a postwar depression due to emotional and physical exhaustion. At another level that was probably not articulated and perhaps not understood, this generation of soldiers was conflicted by the fact they had helped to liberate oppressed people around the globe, but they returned home to a nation that, for the most part, reflected the same racism and sexism that had prevailed before World War II.

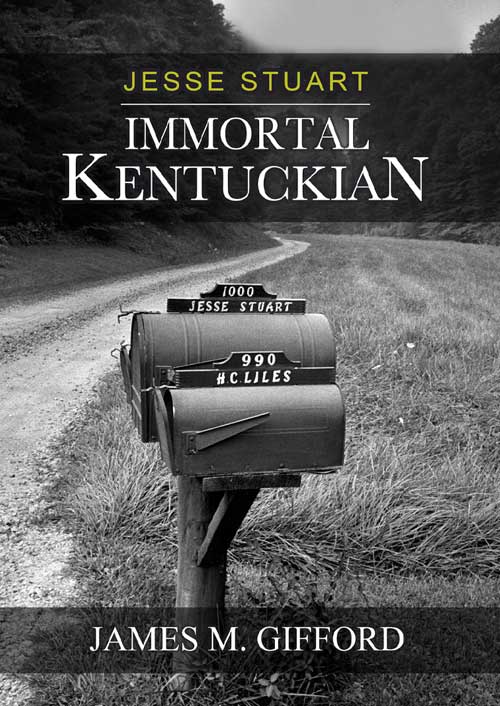

For more information about the Stuarts during and after WWII, see “Jesse Stuart: Immortal Kentuckian,” available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation in Ashland. For more information, contact the JSF at 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Several years ago, as my tribute to Veterans’ Day, I wrote about Willie Sandlin, Kentucky’s only World War I Medal of Honor recipient. Last year, I wrote a lengthy essay, “In Praise of Appalachian Soldiers,” which was serialized in the Daily Independent. This year, I am writing about Jesse Stuart’s service during World War II. In the process of writing about a local sailor, I hope to honor every other man and woman who has served in America’s armed forces.

In 1942, Jesse Stuart tried to enlist in the Army and failed the physical exam. Two years later, Jesse tried to enter the war again by joining the Navy. This time, he passed his physical exam in Huntington, West Virginia, in February, and was sworn in at Louisville on March 31, 1944. He left immediately for basic training at the Great Lakes Training Command near Chicago and was there for fourteen weeks, missing his family, and their “little home, dogs and chickens.”

On July 12, 1944, a month before his thirty-eighth birthday, he graduated and was commissioned as a lieutenant (j.g.). He was assigned to the Bureau of Aeronautics in Washington, D.C., where he worked until the war ended. In the Writers Unit, he was given weak assignments that did not stimulate his cyclonic energy.

Jesse was conflicted over his role in the war. He felt guilty because of the “easy life” he and his co-workers were living in Washington and wondered if he could have been more useful as a farmer than as a bureaucrat in uniform. Meanwhile, his younger brother, James, was in the Leyte, Luzon, and Okinawa invasions.

As with most American families, World War II was a family affair for the Stuarts. While Jesse and James joined two million fellow southerners in uniform, their three sisters worked at the Clayton Lambert munitions plant in Wurtland (Greenup County) during the war. Sophia, Mary, and Glennis were part of a generation of American women who proved that “the woman’s place” was not necessarily in the home. In the national workplace, women replaced men who were serving during World War II and women also, for the first time in American history, served in non-combat jobs in the armed services. More than 250,000 women served as Wacs (Army), Spars (Coast Guard), Waves (Navy), and in the Marine Corps. The “girls behind the men behind the guns” were machinists, storekeepers, clerical workers, and radio operators, and they drove jeeps and trucks and flew airplanes in non-combat roles. During the 1940s, they played an active role in winning a two-front war that spanned the entire globe.

Jesse Stuart was mustered out of the Navy on December 31, 1945. He and his family left Washington “in a hurry” to get home. They departed at noon in poor driving conditions and drove seven and a half hours to Clarksburg, West Virginia, a distance of almost 250 miles.The next day they weathered a “blinding snowstorm and icy roads” to Ohio, where conditions improved for the remainder of the trip. They stayed in Greenup with his wife’s parents for two days, waiting for the ground to freeze so they could drive the rutted dirt roads into their beloved W-Hollow.

More than a decade later, he observed that for “one year after I got out of the service all I wrote should have been burned. What was wrong? You tell me. I don’t know.”

Similarly, after World War II, the great Kentucky writer James Still sat “for months … in the door of [his] log house and could not arouse interest in things [he] had done before.” He eventually began to write again, but his pace was slower, more deliberate–all in all, less enthusiastic. The war had left him a “changed man.” Jesse suffered the same postwar malaise, complaining in 1946 that he didn’t “have any book coming out or any ideas.”

Stuart, Still, and millions of other soldiers suffered a postwar depression due to emotional and physical exhaustion. At another level that was probably not articulated and perhaps not understood, this generation of soldiers was conflicted by the fact they had helped to liberate oppressed people around the globe, but they returned home to a nation that, for the most part, reflected the same racism and sexism that had prevailed before World War II.

For more information about the Stuarts during and after WWII, see “Jesse Stuart: Immortal Kentuckian,” available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation in Ashland. For more information, contact the JSF at 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor