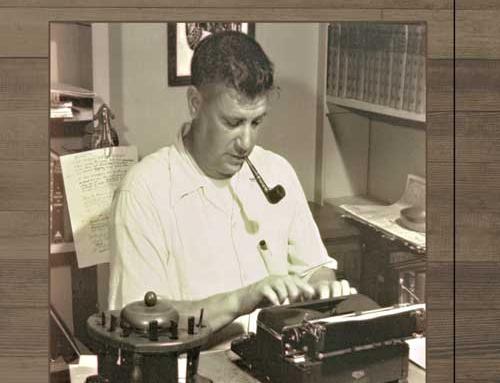

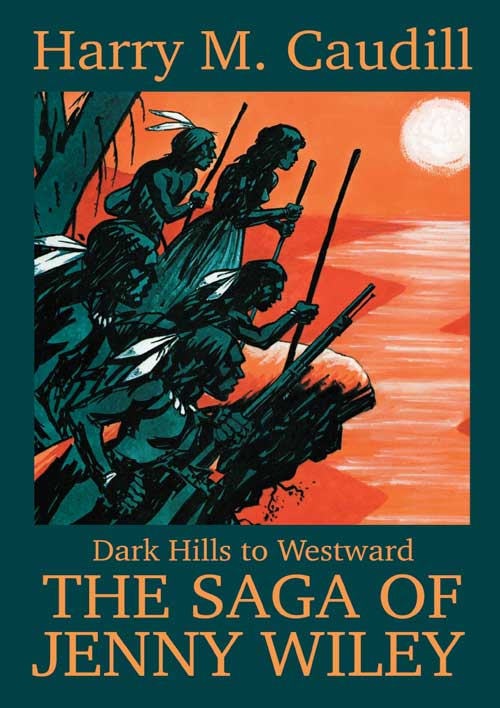

Best known for his nonfiction work “Night Comes to the Cumberlands,” Harry M. Caudill also wrote fiction, including “Dark Hills to Westward: The Saga of Jenny Wiley,” first published in 1969 and recently reprinted in a new softback edition by the Jesse Stuart Foundation.

When Jenny was an old woman, a preacher had sat down with her and wrote out her captivity story. Although Jenny may have embellished it many times, it is the only first-hand account we have, and it’s the primary source for Caudill’s novel.

Briefly, here is her story. Thomas and Jenny Wiley had pioneered land on Walker’s Creek in Bland County, Virginia. On October 1, 1789, while Thomas was away, a small band of Indians, seeking revenge for a recent defeat at the hands of white settlers, attacked the Wiley cabin and killed and scalped Jenny’s three older children and her brother. Jenny, seven months pregnant, was taken captive along with her baby son, Adam.

Briefly, here is her story. Thomas and Jenny Wiley had pioneered land on Walker’s Creek in Bland County, Virginia. On October 1, 1789, while Thomas was away, a small band of Indians, seeking revenge for a recent defeat at the hands of white settlers, attacked the Wiley cabin and killed and scalped Jenny’s three older children and her brother. Jenny, seven months pregnant, was taken captive along with her baby son, Adam.

Then began a nightmare flight through the wilderness into the dark Kentucky hills to westward. Jenny’s only hope for survival was to keep pace with her captors. On the third day, a Cherokee Chief snatched the sick child from its horrified mother and smashed little Adam Wiley’s brains out against a tree. Evading rescue parties, the Indians moved northwest into the Big Sandy Valley of Kentucky. Unable to cross the flood-swollen Ohio River, they retreated to a series of winter camps in present-day Carter, Lawrence, and Johnson counties.

With only a rock bluff for shelter, Jenny spent the winter laboring as a slave. She gave birth in a cave, but three months later the Indians killed and scalped the infant, after it failed to pass their test of courage. After almost a year in captivity, Jenny escaped, miraculously evading pursuit as she made her way to a small settlement at Harman’s Station on John’s Creek. Readers will thrill to the story of her escape and return to her husband.

Immediately upon its publication in 1969, “The Saga of Jenny Wiley” was hailed as a significant contribution to the body of literature and lore that surrounds this frontier heroine.

While reviewers praised “Jenny Wiley,” they also found fault with Caudill’s venture into historical fiction. The book received criticism for poor character development and unconvincing dialogue, but the harshest criticisms concerned Caudill’s treatment of the Indians as simply bloodthirsty savages.

Tom Bethell’s detailed and insightful review in The Mountain Eagle (Whitesburg, Kentucky) offered a middle-ground assessment: “The treatment of Indians weakens this book; but it still a first-rate piece of storytelling – occasionally in a class with Mark Twain and Kenneth Roberts and always unraveled with the kind of persistent enthusiasm that makes Harry Caudill well worth listening to, and well worth reading.”

Today’s readers, be forewarned. If you are looking for a “politically correct” version of race relations, you will not find it here. Like the great fireside storytellers that Harry M. Caudill descended from and represented, he tells a searing story from the perspective of Jenny and her white contemporaries. Readers should keep in mind that Caudill did not write the book as an historian, but as a storyteller, and his goal was to tell Jenny’s story as she experienced it. This book contains descriptions of terrible violence, and I do not recommend it for children or the faint of heart.

The JSF has also published a children’s version of this story. “White Squaw: The True Story of Jennie Wiley” by Arville Wheeler is a 163-page illustrated book for readers in grades 6-8, but high school students and adults will enjoy it, too.

“Dark Hills to Westward: The Saga of Jenny Wiley,” “White Squaw,” and many other books about Kentucky’s and Appalachia’s pioneer heritage are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore in Ashland. For more information, contact the JSF at 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Best known for his nonfiction work “Night Comes to the Cumberlands,” Harry M. Caudill also wrote fiction, including “Dark Hills to Westward: The Saga of Jenny Wiley,” first published in 1969 and recently reprinted in a new softback edition by the Jesse Stuart Foundation.

When Jenny was an old woman, a preacher had sat down with her and wrote out her captivity story. Although Jenny may have embellished it many times, it is the only first-hand account we have, and it’s the primary source for Caudill’s novel.

Briefly, here is her story. Thomas and Jenny Wiley had pioneered land on Walker’s Creek in Bland County, Virginia. On October 1, 1789, while Thomas was away, a small band of Indians, seeking revenge for a recent defeat at the hands of white settlers, attacked the Wiley cabin and killed and scalped Jenny’s three older children and her brother. Jenny, seven months pregnant, was taken captive along with her baby son, Adam.

Then began a nightmare flight through the wilderness into the dark Kentucky hills to westward. Jenny’s only hope for survival was to keep pace with her captors. On the third day, a Cherokee Chief snatched the sick child from its horrified mother and smashed little Adam Wiley’s brains out against a tree. Evading rescue parties, the Indians moved northwest into the Big Sandy Valley of Kentucky. Unable to cross the flood-swollen Ohio River, they retreated to a series of winter camps in present-day Carter, Lawrence, and Johnson counties.

With only a rock bluff for shelter, Jenny spent the winter laboring as a slave. She gave birth in a cave, but three months later the Indians killed and scalped the infant, after it failed to pass their test of courage. After almost a year in captivity, Jenny escaped, miraculously evading pursuit as she made her way to a small settlement at Harman’s Station on John’s Creek. Readers will thrill to the story of her escape and return to her husband.

Immediately upon its publication in 1969, “The Saga of Jenny Wiley” was hailed as a significant contribution to the body of literature and lore that surrounds this frontier heroine.

While reviewers praised “Jenny Wiley,” they also found fault with Caudill’s venture into historical fiction. The book received criticism for poor character development and unconvincing dialogue, but the harshest criticisms concerned Caudill’s treatment of the Indians as simply bloodthirsty savages.

Tom Bethell’s detailed and insightful review in The Mountain Eagle (Whitesburg, Kentucky) offered a middle-ground assessment: “The treatment of Indians weakens this book; but it still a first-rate piece of storytelling – occasionally in a class with Mark Twain and Kenneth Roberts and always unraveled with the kind of persistent enthusiasm that makes Harry Caudill well worth listening to, and well worth reading.”

Today’s readers, be forewarned. If you are looking for a “politically correct” version of race relations, you will not find it here. Like the great fireside storytellers that Harry M. Caudill descended from and represented, he tells a searing story from the perspective of Jenny and her white contemporaries. Readers should keep in mind that Caudill did not write the book as an historian, but as a storyteller, and his goal was to tell Jenny’s story as she experienced it. This book contains descriptions of terrible violence, and I do not recommend it for children or the faint of heart.

The JSF has also published a children’s version of this story. “White Squaw: The True Story of Jennie Wiley” by Arville Wheeler is a 163-page illustrated book for readers in grades 6-8, but high school students and adults will enjoy it, too.

“Dark Hills to Westward: The Saga of Jenny Wiley,” “White Squaw,” and many other books about Kentucky’s and Appalachia’s pioneer heritage are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore in Ashland. For more information, contact the JSF at 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor