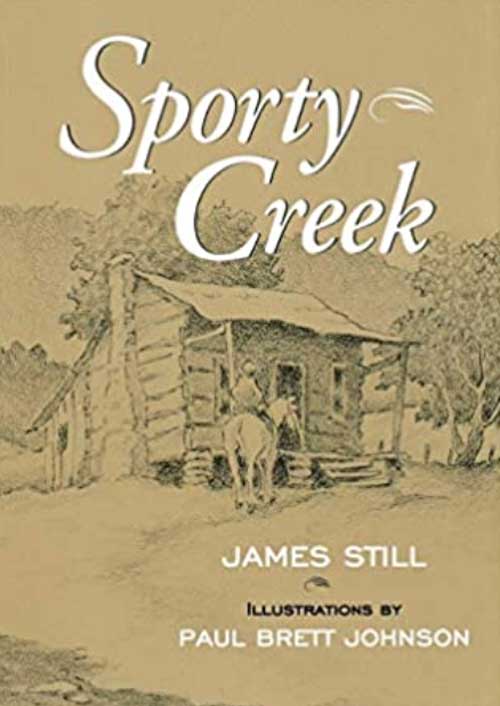

Unlike Harriette Arnow and Jesse Stuart, whose novels have appeared on best-seller lists, James Still (1906-2001) never won a popular national audience. He did, however, win many honors and was well praised by a small but select band of supporters until late in his life when, between 1990 and his death in 2001, the University Press of Kentucky published five of Still’s works, including “Sporty Creek” which had previously been published by Putnam.

Still was born in Lafayette, Alabama, got his A.B. from Lincoln Memorial University (where he knew Stuart), his M.A. from Vanderbilt University, and in June 1931, his B.S. in library science at the University of Illinois, his third degree in as many years.

When he was finishing his library science degree, jobs were scarce because of the Great Depression, and Still wandered over much of the eastern United States doing odd jobs. While working with boys’ clubs in Knott County, Kentucky, he was offered a library job at Hindman Settlement School in 1932. There he stayed for six years, and in his zeal to get books to people in the surrounding countryside he operated a library-on-foot service, carrying books across his shoulders or on a packhorse to one-room schools without libraries.

When he was finishing his library science degree, jobs were scarce because of the Great Depression, and Still wandered over much of the eastern United States doing odd jobs. While working with boys’ clubs in Knott County, Kentucky, he was offered a library job at Hindman Settlement School in 1932. There he stayed for six years, and in his zeal to get books to people in the surrounding countryside he operated a library-on-foot service, carrying books across his shoulders or on a packhorse to one-room schools without libraries.

During this period, Still became well acquainted with mountain people. He carefully observed their ways, their customs, their stories, and their manner of speaking, and he stored them away in notebooks and in memory for later use in the poetry and fiction he began writing in 1935.

He soon became a nationally published author. Writing in 1980 about his earlier years as an author, he said, “Although my stories and poems were appearing in The Atlantic Monthly, The Yale Review, The Virginia Quarterly, and a variety of other publications and I had three published books, I do not recall encountering anybody during these years who had read them. I wrote in an isolation which was virtually total.”

Nevertheless, in 1941 he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and another in 1946 after he got out of the army. Other recognitions that came through the years include awards from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, inclusion of three stories in “Best American Short Stories” and four in the O. Henry Memorial Award Prize Stories (1937, 1938, 1939, 1941).

In 1940, his “River of Earth” enabled him to share the Southern Author’s Award with Thomas Wolfe (for “You Can’t Go Home Again”). He continued to receive awards from Kentucky organizations and honorary degrees from Kentucky universities until his death.

Still’s “Sporty Creek” (1977), subtitled “A novel about an Appalachian boyhood,” comprises ten chapters – or separate stories – which tell of life in the Kentucky hills during the Great Depression. The narrator is a nine-year-old boy whose family, with work almost nonexistent in the mines, moves from place to place, eking out a living as best they can. he novel is not, however, a saga of downtrodden vagrants but of a robust people with courage, a sense of humor, and a zest for life. Like Still’s more famous novel, “River of Earth,” this one tells a compelling story about people who, as they struggle to survive, are acutely aware of themselves and of the world around them.

On Still’s ninetieth birthday, my friend Jim Wayne Miller delivered remarks which were “profoundly moving,” including

“[James Still] is compassionate – to man and beast. Once when he was airing a suit jacket above his quarters, he forgot the jacket and by the time he returned for it, a bird had begun building her nest in one of the pockets. He would not move the jacket, but instead left it hanging there for the bird to lay her eggs and raise her babies. . . .

James Still is not a scholar or an academic – he was destined to be something more – an original source that scholars and academics go to when they want to understand the politics, the economics, the speech, the social arrangements – in short the culture of the place, Southern Appalachia, that he has written about almost exclusively – and beyond that he is the source for a vision of the human experience, most notably found in “River of Earth,” a vision both particular and concrete and at the same time overarchingly universal. James Still’s life and his work blend to make the pattern of the man he is, a pattern no one of us could do wrong emulating.”

If you wish to learn more about James Still’s life, I enthusiastically recommend “James Still: A Life” by Carol Boggess. In this definitive biography of a man who came to be known as the “Dean of Appalachian Literature,” Boggess offers a detailed examination of the life of an Appalachian writer who became a legend in his own lifetime.

James Still’s “Sporty Creek” is the September selection of the Jesse Stuart Foundation’s Regional Readers book discussion group, which will meet on Tuesday, September 27 in the former JSF Conference Room (now Right Eye Graphics); coffee and conversation at 2 p.m. with the book discussion at 2:30 p.m. For more information or to purchase a copy of “Sporty Creek” by phone contact the JSF at 606.326.1667 or e-mail jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Unlike Harriette Arnow and Jesse Stuart, whose novels have appeared on best-seller lists, James Still (1906-2001) never won a popular national audience. He did, however, win many honors and was well praised by a small but select band of supporters until late in his life when, between 1990 and his death in 2001, the University Press of Kentucky published five of Still’s works, including “Sporty Creek” which had previously been published by Putnam.

Still was born in Lafayette, Alabama, got his A.B. from Lincoln Memorial University (where he knew Stuart), his M.A. from Vanderbilt University, and in June 1931, his B.S. in library science at the University of Illinois, his third degree in as many years.

When he was finishing his library science degree, jobs were scarce because of the Great Depression, and Still wandered over much of the eastern United States doing odd jobs. While working with boys’ clubs in Knott County, Kentucky, he was offered a library job at Hindman Settlement School in 1932. There he stayed for six years, and in his zeal to get books to people in the surrounding countryside he operated a library-on-foot service, carrying books across his shoulders or on a packhorse to one-room schools without libraries.

During this period, Still became well acquainted with mountain people. He carefully observed their ways, their customs, their stories, and their manner of speaking, and he stored them away in notebooks and in memory for later use in the poetry and fiction he began writing in 1935.

He soon became a nationally published author. Writing in 1980 about his earlier years as an author, he said, “Although my stories and poems were appearing in The Atlantic Monthly, The Yale Review, The Virginia Quarterly, and a variety of other publications and I had three published books, I do not recall encountering anybody during these years who had read them. I wrote in an isolation which was virtually total.”

Nevertheless, in 1941 he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and another in 1946 after he got out of the army. Other recognitions that came through the years include awards from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, inclusion of three stories in “Best American Short Stories” and four in the O. Henry Memorial Award Prize Stories (1937, 1938, 1939, 1941).

In 1940, his “River of Earth” enabled him to share the Southern Author’s Award with Thomas Wolfe (for “You Can’t Go Home Again”). He continued to receive awards from Kentucky organizations and honorary degrees from Kentucky universities until his death.

Still’s “Sporty Creek” (1977), subtitled “A novel about an Appalachian boyhood,” comprises ten chapters – or separate stories – which tell of life in the Kentucky hills during the Great Depression. The narrator is a nine-year-old boy whose family, with work almost nonexistent in the mines, moves from place to place, eking out a living as best they can. he novel is not, however, a saga of downtrodden vagrants but of a robust people with courage, a sense of humor, and a zest for life. Like Still’s more famous novel, “River of Earth,” this one tells a compelling story about people who, as they struggle to survive, are acutely aware of themselves and of the world around them.

On Still’s ninetieth birthday, my friend Jim Wayne Miller delivered remarks which were “profoundly moving,” including

“[James Still] is compassionate – to man and beast. Once when he was airing a suit jacket above his quarters, he forgot the jacket and by the time he returned for it, a bird had begun building her nest in one of the pockets. He would not move the jacket, but instead left it hanging there for the bird to lay her eggs and raise her babies. . . .

James Still is not a scholar or an academic – he was destined to be something more – an original source that scholars and academics go to when they want to understand the politics, the economics, the speech, the social arrangements – in short the culture of the place, Southern Appalachia, that he has written about almost exclusively – and beyond that he is the source for a vision of the human experience, most notably found in “River of Earth,” a vision both particular and concrete and at the same time overarchingly universal. James Still’s life and his work blend to make the pattern of the man he is, a pattern no one of us could do wrong emulating.”

If you wish to learn more about James Still’s life, I enthusiastically recommend “James Still: A Life” by Carol Boggess. In this definitive biography of a man who came to be known as the “Dean of Appalachian Literature,” Boggess offers a detailed examination of the life of an Appalachian writer who became a legend in his own lifetime.

James Still’s “Sporty Creek” is the September selection of the Jesse Stuart Foundation’s Regional Readers book discussion group, which will meet on Tuesday, September 30 in the former JSF Conference Room (now Right Eye Graphics); coffee and conversation at 2 p.m. with the book discussion at 2:30 p.m. For more information or to purchase a copy of “Sporty Creek” by phone contact the JSF at 606.326.1667 or e-mail jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor