The James Still Room at Morehead State University houses many of the late author’s manuscripts, photographs, documents, books, poems, and personal memorabilia. At one time, this collection also included approximately one dozen high-grade gold figurines, standing no more than four inches tall. Still had brought them to Kentucky from an Ashanti village in Africa (now central Ghana).

Each figurine represented one aspect of daily life in a small African village: women in colorful head gear cooking over an open fire; children playing in the dirt; and men sharpening their weapons, hunting, and carrying their freshly killed game. Because of their cultural and monetary value, these African artifacts were securely locked in a glass display case, and very few people knew their value.

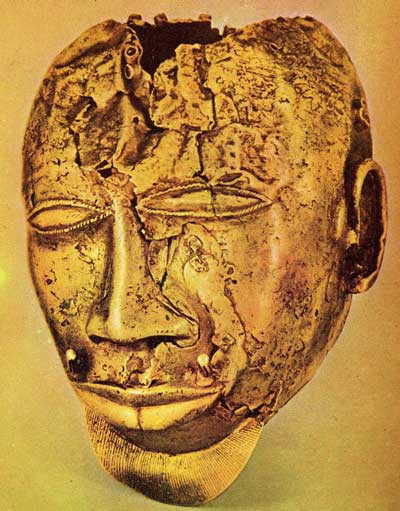

A golden mask of the Ashanti.

How James Still — a librarian, writer, and teacher from eastern Kentucky — came into possession of those rare figurines is an interesting story.

In the 1970s, the university built a new library tower. During the construction, it became necessary to move the James Still Room from the first floor to the second floor. (Later it was moved to the fifth floor of the tower, where it is now located.) Library Director Jack Ellis supervised the move. He and Professor Still personally unlocked the case containing the Ashanti figurines and transported them to their new home on the second floor, where they were secured in another case. Then Still told Ellis the following story about how he happened to become the owner of the tiny African statues.

Many people are not aware that this mild-mannered scholar served in North Africa during World War II, but he spent two-and-a-half years overseas. On one occasion, his B-17 crew flew a trial survival mission into the heart of Africa. When they spotted a large clearing in the jungle, they simulated a crash landing. On the ground and fully armed, the soldiers began scouting out the terrain, planning how best “to survive.” In the course of their exploration, they discovered a small, peaceful Ashanti village.

As GIs often did during World War II, they bartered with the natives for souvenirs; it was called “scrounging.” That is how James Still acquired the valuable figurines from the Ashanti Kingdom. But it is certainly not the end of this story.

Young Sergeant Still shipped his souvenirs home safely. When the war ended in 1945, he headed for home. Like many soldiers, he returned by crossing the Pacific – so that he could say he had been around the world. As a former librarian, the first thing Still did when he landed in San Francisco was visit the public library. Entering the lobby, he saw a locked, well-lit display case attended by a guard. Upon further examination, he was shocked to see that it contained a single object: a small gold figurine, like the ones he had bartered for in the jungle.

Sergeant Still asked the guard if he could speak with the library director. “I have more than a dozen of these things at home in eastern Kentucky,” he told the astounded and skeptical director. After they had spoken at some length about the figurines and the Ashanti, the director decided that the young soldier was telling the truth. In fact, he wanted to visit Hindman, Kentucky, and see the collection for himself. “Of course,” the young sergeant graciously responded. “Come any time.”

A few weeks later, the San Francisco Public Library Director visited the remote Hindman Settlement School to examine the figurines. To protect the collection, should it ever be stolen, he authenticated each piece, catalogued it, photographed it, and registered it at the National Museum of Art.

James Still — the humble librarian, teacher, author, and now African art collector — would later become a giant in the literary world, hence his later appointment as a professor and writer-in-residence at Morehead State University. The figurines remained in the James Still Room of the Camden-Carroll Library until his retirement, when Still donated them to Tuskegee Institute in his native Alabama in honor of the now-famous Tuskegee Airmen of World War II.

The Jesse Stuart Foundation contains a number of books by and about James Still. For more information, contact the JSF at 606-326-1667 or e-mail jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor