Jesse Stuart’s mother, Martha Hilton Stuart, died May 11, 1951. Three years later, on December 23, 1954, Jesse’s father Mitchell (Mick) died. As Mick lay on his death bed, he reflected:

“I’ve been lonesome without Sal for nearly three years and I’d like to see her again. I don’t mind sleeping in Plum Grove clay beside the only woman I ever loved. We had our ups and downs. She was a Baptist and a Democrat and I was a Republican and a Methodist. Her Pap fit for the Gray and my Pap fit for the Blue and our house was divided but I loved her. All I have to do to see her again is just give up.”

Mick’s life was hard. He left the Big Sandy country because of a feud and came to Greenup County where he started his married life in a one-room shack. He mined a coal bank, crawling back in it and working the coal on his back or belly. Mick moved into W-Hollow, cleaning up the land and putting in crops. When his little boy, Herbert, died of pneumonia, Mick sat under a leafless apple tree in January, wrung his hands, and said: “It is too unbearable to stand. If we could have only had a doctor here in time to have saved him.” A few years later, Pa rejoiced with a little baby boy, Lee; but the cold weather, primitive life, and pneumonia killed Lee in April, 1918. Only the very vigorous could survive.

Mick’s life was hard. He left the Big Sandy country because of a feud and came to Greenup County where he started his married life in a one-room shack. He mined a coal bank, crawling back in it and working the coal on his back or belly. Mick moved into W-Hollow, cleaning up the land and putting in crops. When his little boy, Herbert, died of pneumonia, Mick sat under a leafless apple tree in January, wrung his hands, and said: “It is too unbearable to stand. If we could have only had a doctor here in time to have saved him.” A few years later, Pa rejoiced with a little baby boy, Lee; but the cold weather, primitive life, and pneumonia killed Lee in April, 1918. Only the very vigorous could survive.

Some prosperity came when Mitchell got work on the railroad as a section hand. There was plenty of food, and the children were being sent to school; but there were still reminders of the grim life in the hills. Mitchell was summoned to Johnson County to the funeral of his eighty-seven-year-old father who had been bludgeoned to death by feudists. The old man was buried at midnight on a hilltop in order to protect the mourners from attack. An aged soldier spoke a two-sentence eulogy, and Mick and his relatives walked quietly away in the night.

Time and hard work eventually broke Mitchell Stuart’s body. In his last years, he suffered from a bad heart, rupture, high blood pressure, tumor, chronic indigestion, and underweight. For twenty-three years he had walked five miles to work on a railroad section and five miles back. In the winter he left by starlight and returned by it. Life was hard, but he didn’t complain.

In spite of the harshness of his environment, Jesse’s father lived a happy life. One of the greatest sources of pleasure for him was his land. He loved to pick up a handful of freshly plowed earth and fondle and sniff it. He hated to be rootless. He wanted to be firmly attached to his own spot of earth. The day finally came when he bought fifty acres of isolated wooded land. Mick came home that afternoon walking proudly. He was smoking a cigar instead of chewing home-grown Burley tobacco. He was a land owner. He cleared the land and preserved the soil. He sowed the first lespedeza seed seen in his section of the country. He cared for the soil with a passion. He was an earth poet who loved the land and everything on it.

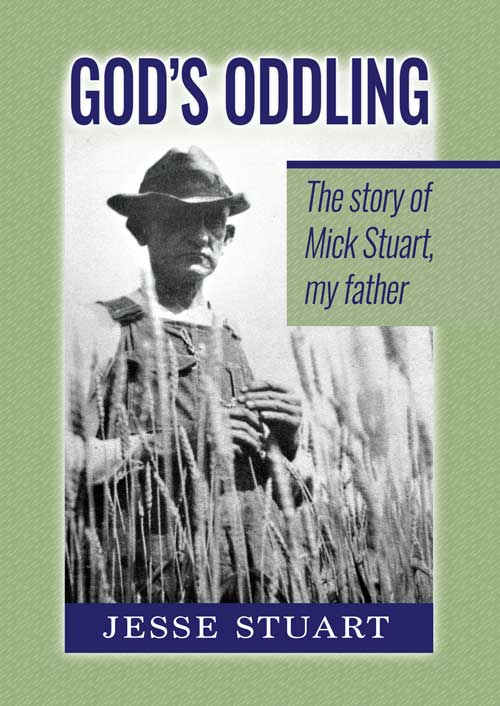

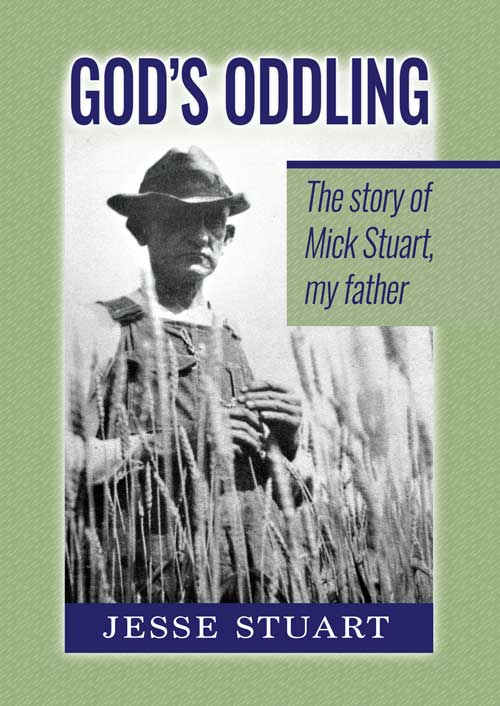

“God’s Oddling, the Story of Mick Stuart, My Father” a 266-page hardback book written by Jesse Stuart has recently been re-published by the Jesse Stuart Foundation. For more information, or to purchase this book, contact the JSF Bookstore at 4440 13th Street in Ashland, call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Jesse Stuart’s mother, Martha Hilton Stuart, died May 11, 1951. Three years later, on December 23, 1954, Jesse’s father Mitchell (Mick) died. As Mick lay on his death bed, he reflected:

“I’ve been lonesome without Sal for nearly three years and I’d like to see her again. I don’t mind sleeping in Plum Grove clay beside the only woman I ever loved. We had our ups and downs. She was a Baptist and a Democrat and I was a Republican and a Methodist. Her Pap fit for the Gray and my Pap fit for the Blue and our house was divided but I loved her. All I have to do to see her again is just give up.”

Mick’s life was hard. He left the Big Sandy country because of a feud and came to Greenup County where he started his married life in a one-room shack. He mined a coal bank, crawling back in it and working the coal on his back or belly. Mick moved into W-Hollow, cleaning up the land and putting in crops. When his little boy, Herbert, died of pneumonia, Mick sat under a leafless apple tree in January, wrung his hands, and said: “It is too unbearable to stand. If we could have only had a doctor here in time to have saved him.” A few years later, Pa rejoiced with a little baby boy, Lee; but the cold weather, primitive life, and pneumonia killed Lee in April, 1918. Only the very vigorous could survive.

Some prosperity came when Mitchell got work on the railroad as a section hand. There was plenty of food, and the children were being sent to school; but there were still reminders of the grim life in the hills. Mitchell was summoned to Johnson County to the funeral of his eighty-seven-year-old father who had been bludgeoned to death by feudists. The old man was buried at midnight on a hilltop in order to protect the mourners from attack. An aged soldier spoke a two-sentence eulogy, and Mick and his relatives walked quietly away in the night.

Time and hard work eventually broke Mitchell Stuart’s body. In his last years, he suffered from a bad heart, rupture, high blood pressure, tumor, chronic indigestion, and underweight. For twenty-three years he had walked five miles to work on a railroad section and five miles back. In the winter he left by starlight and returned by it. Life was hard, but he didn’t complain.

In spite of the harshness of his environment, Jesse’s father lived a happy life. One of the greatest sources of pleasure for him was his land. He loved to pick up a handful of freshly plowed earth and fondle and sniff it. He hated to be rootless. He wanted to be firmly attached to his own spot of earth. The day finally came when he bought fifty acres of isolated wooded land. Mick came home that afternoon walking proudly. He was smoking a cigar instead of chewing home-grown Burley tobacco. He was a land owner. He cleared the land and preserved the soil. He sowed the first lespedeza seed seen in his section of the country. He cared for the soil with a passion. He was an earth poet who loved the land and everything on it.

“God’s Oddling, the Story of Mick Stuart, My Father” a 266-page hardback book written by Jesse Stuart has recently been re-published by the Jesse Stuart Foundation. For more information, or to purchase this book, contact the JSF Bookstore at 4440 13th Street in Ashland, call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor