Throughout the 1700s and 1800s, Americans were afflicted with a case of what John Steinbeck called “westering and westering.”

During the early 1840s, two specific accounts focused the attention of restless Americans on the far West. John C. Fremont led a U.S. Army Survey Expedition, exploring first the Oregon Trail area and then the Pacific Coast region. The published account of Fremont’s expedition was widely read and served to enhance the beauty and potential of California in the national imagination.

A still more widely read account, authored by Lansford Hastings in 1845, advocated a short-cut to California. Rather than following the Oregon Trail past Fort Bridger (in present-day western Wyoming) to Fort Hall (in present-day southern Idaho) and then veering southwest to the headwaters of the Humboldt River and crossing the Sierras, Hastings strongly advocated departing from the Oregon trail at Fort Bridger and then pushing west over the Wasatch Mountains and across the Great Salt Desert to the Humboldt River origins and the Sierras.

A still more widely read account, authored by Lansford Hastings in 1845, advocated a short-cut to California. Rather than following the Oregon Trail past Fort Bridger (in present-day western Wyoming) to Fort Hall (in present-day southern Idaho) and then veering southwest to the headwaters of the Humboldt River and crossing the Sierras, Hastings strongly advocated departing from the Oregon trail at Fort Bridger and then pushing west over the Wasatch Mountains and across the Great Salt Desert to the Humboldt River origins and the Sierras.

This route was, indeed, shorter than the conventional California route, but Hastings, who named the route after himself, had never traveled it, nor had any wagon party. Those few who had crossed this way on horseback swore they would never repeat their near fatal error. Hastings’ travel guide, however, became a national best-seller and became a well-thumbed Bible for tens of thousands of “westering” Americans.

Of the hundreds of wagon trains which headed west during this period, only one—the Donner-Reed party—left an indelible imprint on our national imagination. This train’s fame was sealed by its terrible fate. Influenced by Hastings’ fraudulent claims of a 300-mile shortcut and already significantly behind the standard, accepted summer schedule for making the long trip, the Donner-Reed party made a tragic error: they took the virtually untried “Hastings Cutoff” and consequently lost weeks and weeks of time in their arduous struggle to drive their wagons first over the nearly impassable Wasatch Mountains and then across the even more formidable vast salt desert west of the Great Salt Lake

Exhausted and demoralized, they finally ascended the Sierra Nevadas, only to be overwhelmed near the summit by the icy grip of an early winter. Trapped, the Donner-Reed party built crude shelters and struggled to survive through the winter in extremely deep snow and sub-zero temperatures.

Soup made of boiled leather and powdered bones became a luxury. In the late stages of their unspeakably harrowing ordeal, some party members resorted to cannibalism. Of the 79 persons who started, 34 died before several rescue expeditions out of California finally reached the survivors.

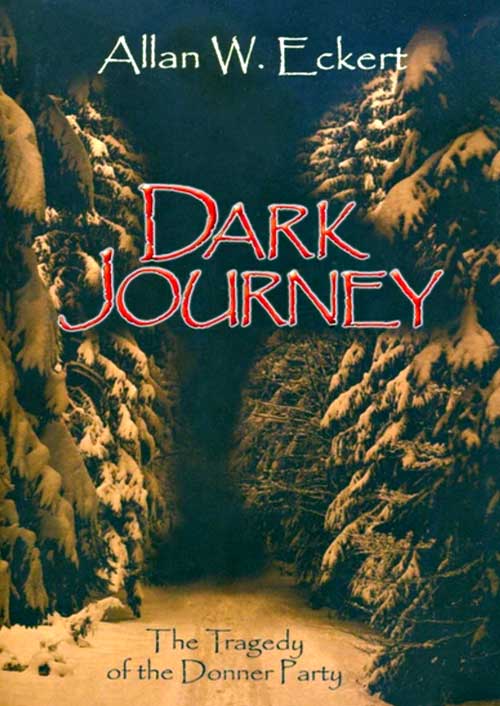

Allan Eckert’s compelling book, “Dark Journey: The Tragedy of the Donner Party,” published by the JSF in 2009, provides a rigorously accurate and comprehensive, yet poignant and dramatic presentation of the Donner-Reed Wagon Train’s grim odyssey from Illinois westward to California, beginning in the spring of 1846 and finally—mercifully—ending in the spring of the following year. It is the result of Eckert’s extended and intensive research through a multitude of original documents and contemporary accounts of this haunting chapter in American history.

This book—written near the end of Eckert’s life—will be an important addition to any home, school, or public library. The Jesse Stuart Foundation contains 189 copies of this 334-page hardcover First Edition book. Each book is signed and inscribed by the author; the price is $35.00. For more information, call the Jesse Stuart Foundation at 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Throughout the 1700s and 1800s, Americans were afflicted with a case of what John Steinbeck called “westering and westering.”

During the early 1840s, two specific accounts focused the attention of restless Americans on the far West. John C. Fremont led a U.S. Army Survey Expedition, exploring first the Oregon Trail area and then the Pacific Coast region. The published account of Fremont’s expedition was widely read and served to enhance the beauty and potential of California in the national imagination.

A still more widely read account, authored by Lansford Hastings in 1845, advocated a short-cut to California. Rather than following the Oregon Trail past Fort Bridger (in present-day western Wyoming) to Fort Hall (in present-day southern Idaho) and then veering southwest to the headwaters of the Humboldt River and crossing the Sierras, Hastings strongly advocated departing from the Oregon trail at Fort Bridger and then pushing west over the Wasatch Mountains and across the Great Salt Desert to the Humboldt River origins and the Sierras.

This route was, indeed, shorter than the conventional California route, but Hastings, who named the route after himself, had never traveled it, nor had any wagon party. Those few who had crossed this way on horseback swore they would never repeat their near fatal error. Hastings’ travel guide, however, became a national best-seller and became a well-thumbed Bible for tens of thousands of “westering” Americans.

Of the hundreds of wagon trains which headed west during this period, only one—the Donner-Reed party—left an indelible imprint on our national imagination. This train’s fame was sealed by its terrible fate. Influenced by Hastings’ fraudulent claims of a 300-mile shortcut and already significantly behind the standard, accepted summer schedule for making the long trip, the Donner-Reed party made a tragic error: they took the virtually untried “Hastings Cutoff” and consequently lost weeks and weeks of time in their arduous struggle to drive their wagons first over the nearly impassable Wasatch Mountains and then across the even more formidable vast salt desert west of the Great Salt Lake

Exhausted and demoralized, they finally ascended the Sierra Nevadas, only to be overwhelmed near the summit by the icy grip of an early winter. Trapped, the Donner-Reed party built crude shelters and struggled to survive through the winter in extremely deep snow and sub-zero temperatures.

Soup made of boiled leather and powdered bones became a luxury. In the late stages of their unspeakably harrowing ordeal, some party members resorted to cannibalism. Of the 79 persons who started, 34 died before several rescue expeditions out of California finally reached the survivors.

Allan Eckert’s compelling book, “Dark Journey: The Tragedy of the Donner Party,” published by the JSF in 2009, provides a rigorously accurate and comprehensive, yet poignant and dramatic presentation of the Donner-Reed Wagon Train’s grim odyssey from Illinois westward to California, beginning in the spring of 1846 and finally—mercifully—ending in the spring of the following year. It is the result of Eckert’s extended and intensive research through a multitude of original documents and contemporary accounts of this haunting chapter in American history.

This book—written near the end of Eckert’s life—will be an important addition to any home, school, or public library. The Jesse Stuart Foundation contains 189 copies of this 334-page hardcover First Edition book. Each book is signed and inscribed by the author; the price is $35.00. For more information, call the Jesse Stuart Foundation at 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor