In some parts of America, the “intellectual leaders” fancy themselves much too deep to be understood by everyday folks like you and me. Not so in Appalachia!

Our intellectual leaders have been kind, loving, accessible men and women who represent, with their own lives, what Appalachia is really all about.

During my 37 years at the JSF, we have lost some of our best and brightest leaders, giants of literacy and learning: Jesse Stuart, James Still, Cratis Williams, Jim Wayne Miller, Harry M. Caudill, John Stephenson, Wilma Dykeman, Allan Eckert, Billy C. Clark, Thomas D. Clark, and many others.

Fortunately, many remain. Loyal Jones, Edwina Pendarvis, Carol Boggess, Stan Bumgardner, Hal Blythe, Charlie Sweet, Gurney Norman, Silas House and hundreds of others “soldier on,” as the late James Still often said of his own ongoing writing efforts.

Fortunately, many remain. Loyal Jones, Edwina Pendarvis, Carol Boggess, Stan Bumgardner, Hal Blythe, Charlie Sweet, Gurney Norman, Silas House and hundreds of others “soldier on,” as the late James Still often said of his own ongoing writing efforts.

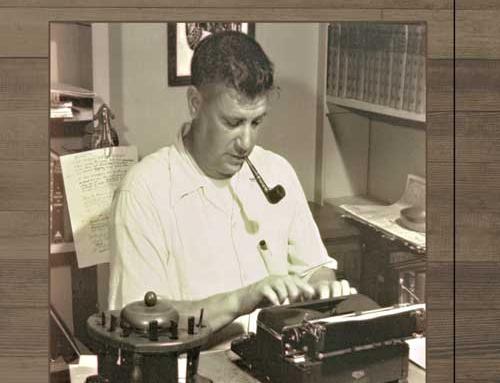

Among our deceased intellectual leaders, one of my favorites is native son Billy C. Clark. The JSF manages his literary properties and has reprinted Clark’s autobiographical classic, “A Long Row To Hoe,” in a soft-back edition.

In this fascinating and highly readable book, Clark writes of his own astonishingly primitive childhood in an Appalachian river town, Catlettsburg, Kentucky, at the junction of the Big Sandy and Ohio Rivers.

Clark was a member of a sprawling, ragged family. His father was an intelligent, fiddle-playing shoemaker with little formal education. His mother often took in washings to help provide food for the family.

Billy grew up in a derelict house, “The Leaning Tower” on the banks of the Ohio. Always hungry, often dirty, and without adequate clothing, he led an adventurous life on the two rivers, swimming, fishing, and salvaging flotsam from the frequent floods.

He set trotlines for fish and trap lines for mink and muskrats, and he walked 14 miles before school to clear his traps.

He learned laughter from his magnificent mother and wisdom from his father, who taught him that “poor folks have a long row to hoe. …”

Billy was the only one of his family to seek an education, and through his traps, his river salvage, and odd jobs, he earned money to put himself through school.

The book ends with a powerful account of his parents’ pride at his high school graduation.

“A Long Row To Hoe” is as American as “Huckleberry Finn.” It is a touching account of a boy and two rivers. It is a must for public and school libraries, or anyone interested in Appalachian history or literature.

Billy C. Clark’s books are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation, 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

In some parts of America, the “intellectual leaders” fancy themselves much too deep to be understood by everyday folks like you and me. Not so in Appalachia!

Our intellectual leaders have been kind, loving, accessible men and women who represent, with their own lives, what Appalachia is really all about.

During my 37 years at the JSF, we have lost some of our best and brightest leaders, giants of literacy and learning: Jesse Stuart, James Still, Cratis Williams, Jim Wayne Miller, Harry M. Caudill, John Stephenson, Wilma Dykeman, Allan Eckert, Billy C. Clark, Thomas D. Clark, and many others.

Fortunately, many remain. Loyal Jones, Edwina Pendarvis, Carol Boggess, Stan Bumgardner, Hal Blythe, Charlie Sweet, Gurney Norman, Silas House and hundreds of others “soldier on,” as the late James Still often said of his own ongoing writing efforts.

Among our deceased intellectual leaders, one of my favorites is native son Billy C. Clark. The JSF manages his literary properties and has reprinted Clark’s autobiographical classic, “A Long Row To Hoe,” in a soft-back edition.

In this fascinating and highly readable book, Clark writes of his own astonishingly primitive childhood in an Appalachian river town, Catlettsburg, Kentucky, at the junction of the Big Sandy and Ohio Rivers.

Clark was a member of a sprawling, ragged family. His father was an intelligent, fiddle-playing shoemaker with little formal education. His mother often took in washings to help provide food for the family.

Billy grew up in a derelict house, “The Leaning Tower” on the banks of the Ohio. Always hungry, often dirty, and without adequate clothing, he led an adventurous life on the two rivers, swimming, fishing, and salvaging flotsam from the frequent floods.

He set trotlines for fish and trap lines for mink and muskrats, and he walked 14 miles before school to clear his traps.

He learned laughter from his magnificent mother and wisdom from his father, who taught him that “poor folks have a long row to hoe. …”

Billy was the only one of his family to seek an education, and through his traps, his river salvage, and odd jobs, he earned money to put himself through school.

The book ends with a powerful account of his parents’ pride at his high school graduation.

“A Long Row To Hoe” is as American as “Huckleberry Finn.” It is a touching account of a boy and two rivers. It is a must for public and school libraries, or anyone interested in Appalachian history or literature.

Billy C. Clark’s books are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation, 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor