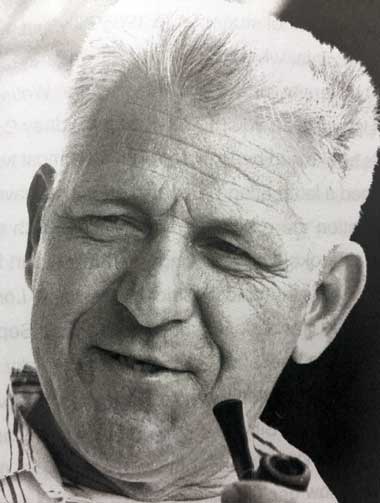

Billy C. Clark began life in storybook fashion.

On December 29, 1928, Bertha Clark, who was pregnant with her seventh child, went to Huntington, West Virginia, to shop for second-hand clothes for her six children. While shopping, she experienced labor pains. Quickly gathering her purchases, she boarded a streetcar and headed home. One thought occupied her mind: she was determined that her child would not be born a “foreigner.”

The streetcar ride brought more pains. As Mrs. Clark gritted her teeth and searched for the Big Sandy, the driver noticed her.

The streetcar ride brought more pains. As Mrs. Clark gritted her teeth and searched for the Big Sandy, the driver noticed her.

“Something wrong, lady?” he asked as he stopped the streetcar to let a passenger off.

“I’m going to have a baby,” she said.

“Not here in the streetcar!” the driver yelled. “Hold it! Hold it!”

“How far till we cross the Big Sandy?” she asked in desperation.

“Not far,” the driver answered. “How far do you live from the end of the bridge?”

Below the mouth of Catlettscreek,” she said.

He pushed the streetcar as fast as it would go. The rest of the passengers shouted and quarreled as the driver passed their stops, refusing to let them off. Now and then he looked over at Mrs. Clark, “Hold it, lady! Hold it just a little longer!”

When Billy Curtis Clark was born on Kentucky soil that day, he seemed to be just another child born into Appalachian poverty. Billy’s father, Mason, was a cobbler and mountain fiddler. His mother Bertha took in washing and “scrubbed until her hands bled,” but she often gave to needier families.

Billy left home when he was eleven years old, and for the next five years he lived on the third floor of the City Building in Catlettsburg while he worked his way through high school. “I cleaned the men’s and women’s jails,” he remembered, “wound the town clock, and served as a volunteer fireman.” He also fished, trapped, picked berries to sell, and worked at odd jobs.

After high school, an almost three-year stint in the Army made Billy eligible for educational benefits under the G.I. Bill, and he enrolled at the University of Kentucky in the fall of 1952. For financial reasons, he left college without a degree in 1955 and proceeded to publish five books with New York publishers including his classic coming of age memoir, A Long Row to Hoe (1960).

In 1956, Billy had returned home and was working for Ashland Oil when he met and married Ruth Bocook, also a native of Catlettsburg. Billy’s second cousin Jesse Stuart and his wife Deane “stood up with them” when they married in July. In 1963, he returned to finish his coursework at UK, and graduated in 1967. In 1985 Billy and Ruth moved to Farmville, Virginia, where he served as writer-in-residence at Longwood University and founded Virginia Writing. He left Longwood University in 2003 for Hampton-Sydney College.

Clark’s books had been out of print for almost two decades when he signed a letter of agreement in 1991 that gave the Jesse Stuart Foundation the exclusive rights to republish and market his out-of-print books. The following year, the Stuart Foundation republished Clark’s autobiographical classic, A Long Row To Hoe. That fall, the city of Catlettsburg proclaimed September 5th “Billy C. Clark Day,” because the state of Kentucky had named the bridge leading from Catlettsburg to Kenova, West Virginia, the “Billy C. Clark Bridge.” Billy also served as Grand Marshall of the Catlettsburg Labor Day Parade that year. A mural on the floodwall in Catlettsburg now depicts Billy C. Clark and his books.

The gradual reissue of Clark’s books created a renaissance of interest in his life and works that resulted in a flood of new publications. Like most successful writers, Billy Clark published extensively in periodicals and participated in numerous writing workshops, literary festivals, and book fairs.

Billy Clark loved conversations, and all who knew him remember him as an enthusiastic storyteller. Once, when Billy and I were driving from Ashland to Oil Springs Elementary School in Johnson County, I remember lowering my window a couple of inches. I suspect that I felt so overwhelmed by Billy’s avalanche of words that I was giving some of them a chance to escape into the Big Sandy Valley, a region that Billy Clark truly knew and loved.

Billy’s “brother by mutual adoption,” Frosty Lockwood once observed that being in a car with Billy for eight hours “was like being locked in a moving boxcar with a wild horse. It’s dark. You’re off balance you don’t know which direction you’re going to get kicked from.” Since Billy’s death March 15, 2009, my memories of our long trips together and his stories, supercharged with hyperbole, always make me smile.

Now he belongs to the ages. It is easy to imagine him in well-worn fishing garb talking with his heavenly Father: “Lord, I know you’ve been listening in on some of those stories that my Catlettsburg friends have been telling on me. Now here’s what really happened . . .” And the Lord smiles, wondering if eternity will be quite long enough for the old muskrat hunter to complete his report.

Billy C. Clark rose from poverty to become a nationally famous educator and author. Thanks to his mother’s courageous journey in 1928, the Commonwealth of Kentucky lists him as one of its finest writers.

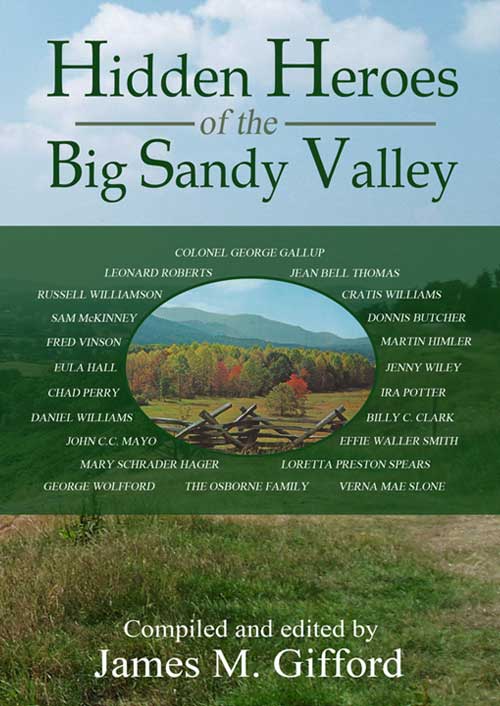

The works of Billy C. Clark are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Appalachian Gift Shop at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, call 606.326.1667 or e-mail jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Billy C. Clark began life in storybook fashion.

On December 29, 1928, Bertha Clark, who was pregnant with her seventh child, went to Huntington, West Virginia, to shop for second-hand clothes for her six children. While shopping, she experienced labor pains. Quickly gathering her purchases, she boarded a streetcar and headed home. One thought occupied her mind: she was determined that her child would not be born a “foreigner.”

The streetcar ride brought more pains. As Mrs. Clark gritted her teeth and searched for the Big Sandy, the driver noticed her.

“Something wrong, lady?” he asked as he stopped the streetcar to let a passenger off.

“I’m going to have a baby,” she said.

“Not here in the streetcar!” the driver yelled. “Hold it! Hold it!”

“How far till we cross the Big Sandy?” she asked in desperation.

“Not far,” the driver answered. “How far do you live from the end of the bridge?”

Below the mouth of Catlettscreek,” she said.

He pushed the streetcar as fast as it would go. The rest of the passengers shouted and quarreled as the driver passed their stops, refusing to let them off. Now and then he looked over at Mrs. Clark, “Hold it, lady! Hold it just a little longer!”

When Billy Curtis Clark was born on Kentucky soil that day, he seemed to be just another child born into Appalachian poverty. Billy’s father, Mason, was a cobbler and mountain fiddler. His mother Bertha took in washing and “scrubbed until her hands bled,” but she often gave to needier families.

Billy left home when he was eleven years old, and for the next five years he lived on the third floor of the City Building in Catlettsburg while he worked his way through high school. “I cleaned the men’s and women’s jails,” he remembered, “wound the town clock, and served as a volunteer fireman.” He also fished, trapped, picked berries to sell, and worked at odd jobs.

After high school, an almost three-year stint in the Army made Billy eligible for educational benefits under the G.I. Bill, and he enrolled at the University of Kentucky in the fall of 1952. For financial reasons, he left college without a degree in 1955 and proceeded to publish five books with New York publishers including his classic coming of age memoir, A Long Row to Hoe (1960).

In 1956, Billy had returned home and was working for Ashland Oil when he met and married Ruth Bocook, also a native of Catlettsburg. Billy’s second cousin Jesse Stuart and his wife Deane “stood up with them” when they married in July. In 1963, he returned to finish his coursework at UK, and graduated in 1967. In 1985 Billy and Ruth moved to Farmville, Virginia, where he served as writer-in-residence at Longwood University and founded Virginia Writing. He left Longwood University in 2003 for Hampton-Sydney College.

Clark’s books had been out of print for almost two decades when he signed a letter of agreement in 1991 that gave the Jesse Stuart Foundation the exclusive rights to republish and market his out-of-print books. The following year, the Stuart Foundation republished Clark’s autobiographical classic, A Long Row To Hoe. That fall, the city of Catlettsburg proclaimed September 5th “Billy C. Clark Day,” because the state of Kentucky had named the bridge leading from Catlettsburg to Kenova, West Virginia, the “Billy C. Clark Bridge.” Billy also served as Grand Marshall of the Catlettsburg Labor Day Parade that year. A mural on the floodwall in Catlettsburg now depicts Billy C. Clark and his books.

The gradual reissue of Clark’s books created a renaissance of interest in his life and works that resulted in a flood of new publications. Like most successful writers, Billy Clark published extensively in periodicals and participated in numerous writing workshops, literary festivals, and book fairs.

Billy Clark loved conversations, and all who knew him remember him as an enthusiastic storyteller. Once, when Billy and I were driving from Ashland to Oil Springs Elementary School in Johnson County, I remember lowering my window a couple of inches. I suspect that I felt so overwhelmed by Billy’s avalanche of words that I was giving some of them a chance to escape into the Big Sandy Valley, a region that Billy Clark truly knew and loved.

Billy’s “brother by mutual adoption,” Frosty Lockwood once observed that being in a car with Billy for eight hours “was like being locked in a moving boxcar with a wild horse. It’s dark. You’re off balance you don’t know which direction you’re going to get kicked from.” Since Billy’s death March 15, 2009, my memories of our long trips together and his stories, supercharged with hyperbole, always make me smile.

Now he belongs to the ages. It is easy to imagine him in well-worn fishing garb talking with his heavenly Father: “Lord, I know you’ve been listening in on some of those stories that my Catlettsburg friends have been telling on me. Now here’s what really happened . . .” And the Lord smiles, wondering if eternity will be quite long enough for the old muskrat hunter to complete his report.

Billy C. Clark rose from poverty to become a nationally famous educator and author. Thanks to his mother’s courageous journey in 1928, the Commonwealth of Kentucky lists him as one of its finest writers.

The works of Billy C. Clark are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Appalachian Gift Shop at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, call 606.326.1667 or e-mail jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor