In 1957, Marty Robbins wrote and sang a song filled with teen angst that became number one on the country chart. “A White Sports Coat and a Pink Carnation” told the story of a young man who was “all dressed up for the dance,” but his date changed her mind and he was “all alone in romance.”

In the spring of 1962, when I was a senior in high school, I went to a department store in my hometown to purchase a white sports coat. I could not dance, and my family had no car, so I had no prospects for romance, but I did hope to attend some church and school activities in fashionable attire.

The coat cost $20. From my after school job, I had $10 to “put down” on the coat and promised to pay the remaining $10 the following week. The department store owner refused to let me take the coat, unless I could pay the full amount. “You know me,” I protested as strongly as truly poor people were allowed to protest. “You know my Grandmother and my Uncles. You know I’ll pay you!”

“Borrow the money from one of your Uncles,” he said, and turned to attend to other matters. As I trudged home in the ill-fitting shoes that permanently damaged my feet, I wrestled with my disappointment: “Why, any other boy on the basketball team could have walked in there and walked out with that coat,” I thought. I was the student body president, an Eagle Scout, an honor roll student, and a varsity athlete, but my family was very poor and sadly that made me a bad $10 credit risk to a local merchant.

This was not some traumatizing watershed event in my life. It was just one of a thousand pieces of the quilt of poverty that covered me and hundreds of thousands of Appalachian people like me in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s.

Long before the Federal government created a welfare system that is one of the most horrible open wounds on our society, the Appalachian poor had two choices: pay cash or do without.

So we learned to do without and became a culture whose financial values paralleled the values of the Great Depression generation. We chose to save rather than spend. We gave money generously to family and friends, but refused to spend it on ourselves. We feared banks, cashed our checks, and paid our bills with “cash money.”

We began working as children and worked hard almost every day of our lives. Every day of work and every dollar earned separated us from our poverty, so we worked with a fierce determination, always looking over our shoulder to see if the grim spectre of poverty was still behind us, wondering if it was possible to distance ourselves forever from its clutches.

Gradually, we came to love work, because work saved us, and we saw in work a nobility and honor that others did not see. We loved work more than love, for work rarely disappointed us. Even when we became “too old to work,” we still worked, because work defined us.

Eventually, we saved enough money to stay our fears, buy a home, and build more confident lives. Yet we still felt guilty when we bought something that cost more than $50, because it made us think of all the sacrifices that our parents and grandparents had made and all the things they had done without. We felt unworthy.

Of course, these general themes do not hold true for all Appalachian people. Many, for example, received credit and “owed their souls to the company store” or to local merchants. And yet these reflections are painfully accurate for millions of Appalachian people born between 1900 and 1950.

The culture of poverty has marked millions of us in ways that the mall generation will never understand. They are amazed that their grandparents saved so much money, but they’re glad we did. One day when we’re gone and they inherit our hard-earned savings, I hope they inherit some of our financial values, too.

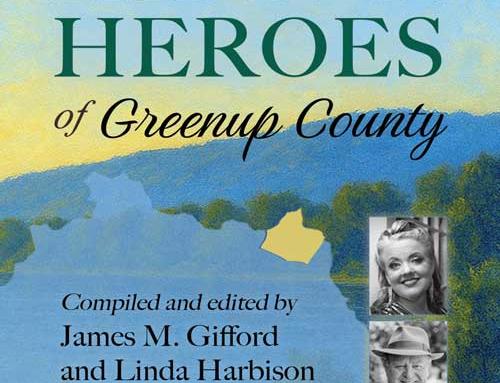

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor