The wisest man I ever knew—we called him Zayde, born 1903, Minsk, Belarus—once told me a story of a man on a train going from coast to coast. The train had no dining car. One stop was planned at a half-way point. There at trackside, a banquet would await the travelers. Caviar, goat’s cheese, olives, fresh melons, figs and dates, soups hot and cold, rolls baked in a hickory wood stove, roast duck, sugar cured ham, turkey with three kinds of stuffing, sweet potatoes, snap peas, baby carrots, and on and on through a table laden with hand-cranked ice cream and prizewinning pumpkin and mince pies. But, there were rules. The train would stop for only half an hour, and no food could be brought on board. This, Zayde explained, is an allegory of our lives here on earth—for those of inquisitive mind.

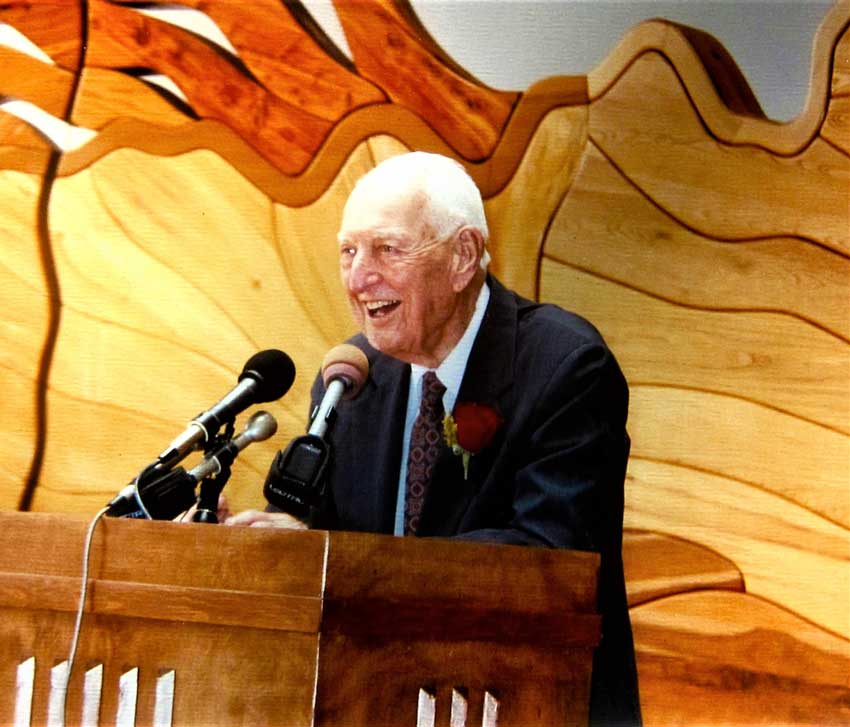

So…now you know how I felt on the eighteenth of July, 1998. No, I don’t file such data in my mind, but I do have a copy of The Wolfpen Notebooks signed by James Still at the celebration of his 92d birthday. All was well with the world that day at Little Carr Creek: Mr. Still in straw hat surrounded by children; Helen Earp in peach colored blouse smiling over a table of books—River of Earth, Jack Tales, The Notebooks; Kentucky historian, “Timeless Thomas” Clark—wife at his side—beaming with a smile to rival that of former Governor Happy Chandler’s. Music filled the air—Lee Sexton on banjo, Ray Sloane on fiddle, Jennifer Krieger humming along; and under a walnut tree a fellow pinged out notes on a hammer dulcimer as a little boy, walnut in each hand, watched. I drifted toward the cabin. The big metal wash tub hanging by the kitchen door was garlanded to the rooftop by Virginia creeper, five leaflet fingers waving on each stem, sparkling in sunlight. A rough-hewn table, an appendage of that old log cabin , was decked with pottery, and held out a clear glass jar of Queen Anne’s lace and black-eyed Susans one of which, if I’d been a child, I’d have taken.

Inside were Mason jars of home-canned food, pegs for shirts and coats, a wooden hand-crank telephone, and the simplest necessities for cooking, washing, and shaving, a water pail and dipper, and a flyswatter, bright red with white handle. The bed was spread with a hand-made quilt which I’d have bet money was very likely one of Verna Mae Slone’s. At the head of the bed was a large portrait of Mr. Still at ease in his wicker rocking chair, book in hand, staring curiously at his visitor.

This chair was the spot I was drawn to. I turned around, and there it stood—empty. There I stole a few moments to sit, pretending—wishing—that I could sit there all day, and another day, or maybe a week—maybe all summer. Around me were shelves of books from floor to ceiling. Books Mr. Still had collected, read, shared. Books on topics as diverse as trees, trails, travels, travails, great thoughts, simple thoughts, struggles, and sayings like those my old Aunt Nell loved and treasured—sayings by people she loved so dearly…”he’s so slow he could fall out of a tree and never get hurt.”

I was sitting at a banquet of the mind. Yet, I had but half an hour.

By Robert French

Thomas Clark, 100th birthday celebration; wood from Clark’s woodland property (Center for Kentucky Archives, Frankfort KY).