For more than four years, I have been working on a collection of essays about the depression decade in eastern Kentucky. That work has intensified my interest in Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor. With a presidential election imminent, I thought my readers would enjoy reading more about the Roosevelts.

The president is the central person in the American political system. That would seem to contradict the intentions of the Founding Fathers. Remembering the horrid example of the British monarchy, they invented a separation of powers in order, as Justice Brandeis later put it, “to preclude the exercise of arbitrary power.” Accordingly, they divided the government into three equal and coordinate branches—the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary.

But a system based on the tripartite separation of powers has an inherent tendency toward inertia and stalemate. One of the three branches must take the initiative if the system is to move. The executive branch alone is structurally capable of taking that initiative. The Founders must have sensed this when they accepted Alexander Hamilton’s proposition in the Seventieth Federalist paper that “energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of good government.” They thus envisaged a strong president—but within an equally strong system of constitutional accountability. (The term “imperial presidency” arose in the 1970s to describe a situation when the balance of power and accountability is upset in favor of the executive.)

But a system based on the tripartite separation of powers has an inherent tendency toward inertia and stalemate. One of the three branches must take the initiative if the system is to move. The executive branch alone is structurally capable of taking that initiative. The Founders must have sensed this when they accepted Alexander Hamilton’s proposition in the Seventieth Federalist paper that “energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of good government.” They thus envisaged a strong president—but within an equally strong system of constitutional accountability. (The term “imperial presidency” arose in the 1970s to describe a situation when the balance of power and accountability is upset in favor of the executive.)

The American system of self-government thus comes to focus in the presidency— “the vital place of action in the system,” as Woodrow Wilson put it. Henry Adams, himself the great-grandson and grandson of presidents as well as a truly brilliant American historian, said that the American president “resembles the commander of a ship at sea. He must have a helm to grasp, a course to steer, a port to seek.”

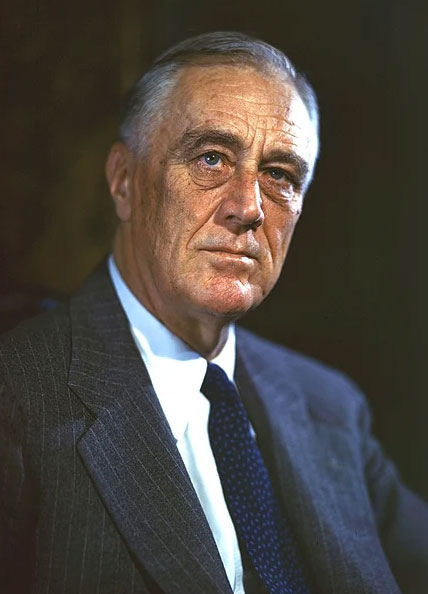

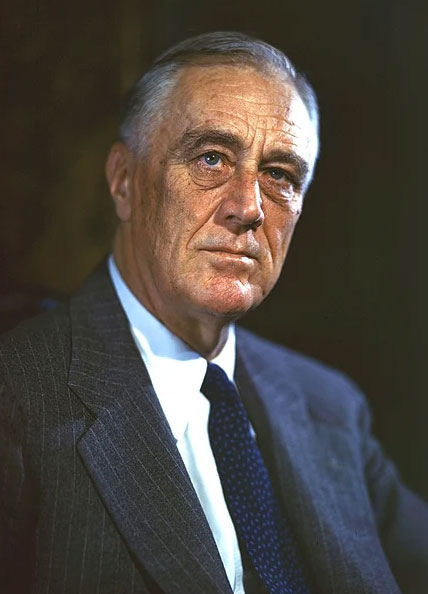

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a statesman whose massive achievements tower over the twentieth century. In a ranking of American presidents, he is rivaled only by George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. He was elected to an unprecedented four terms in office, and his accomplishments in leading the nation through the depression and a world war resonate to this day.

Roosevelt’s presidency was one of the most eventful in U.S. history. He took office in the midst of economic crisis: the stock market had crashed, the banking system had collapsed, and millions of Americans were unemployed. Galvanizing the nation with his 1933 inaugural address and with a flurry of legislation in the First Hundred Days, Roosevelt demonstrated an optimism and resolve that garnered quick support for his administration and for the programs that he called the New Deal. And he was the first president truly to understand the power of the new mass media, rallying the nation through “fireside chats” on the radio and speeches that were the mainstay of movie house newsreels.

In acute, stylish prose, Roy Jenkins—who was a prominent British politician as well as a bestselling historian—tackles all of the complexities and intricacies of Roosevelt’s character in his short biography, “Franklin Delano Roosevelt,” a 2003 entry in the American Presidents series published by Times Books and Henry Holt and Company. Though not an intellectual himself, Roosevelt was nonetheless able to inspire the intellectual classes. He was from the American upper class, and yet his greatest talent was his ability to inspire confidence among working people during a time of economic and international turmoil. He did that by being honest and trustworthy. And when he had to shift his priorities after Pearl Harbor from (in his words) “Dr. New Deal” to “Dr. Win-the War,” he did so without any loss in the people’s confidence.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the dominant president of the twentieth century, helped the United States become the most influential world power. Roy Jenkins’s keen assessment enables us to understand how he accomplished this and why he still stands tall in our estimation today.

For more information about the Roosevelts, the JSF has six excellent books in stock. Contact the Jesse Stuart Foundation at 4440 13th Street in Ashland by phone at 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

James M. Gifford, Ph.D.

CEO & Senior Editor

Jesse Stuart Foundation

For more than four years, I have been working on a collection of essays about the depression decade in eastern Kentucky. That work has intensified my interest in Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor. With a presidential election imminent, I thought my readers would enjoy reading more about the Roosevelts.

The president is the central person in the American political system. That would seem to contradict the intentions of the Founding Fathers. Remembering the horrid example of the British monarchy, they invented a separation of powers in order, as Justice Brandeis later put it, “to preclude the exercise of arbitrary power.” Accordingly, they divided the government into three equal and coordinate branches—the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary.

But a system based on the tripartite separation of powers has an inherent tendency toward inertia and stalemate. One of the three branches must take the initiative if the system is to move. The executive branch alone is structurally capable of taking that initiative. The Founders must have sensed this when they accepted Alexander Hamilton’s proposition in the Seventieth Federalist paper that “energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of good government.” They thus envisaged a strong president—but within an equally strong system of constitutional accountability. (The term “imperial presidency” arose in the 1970s to describe a situation when the balance of power and accountability is upset in favor of the executive.)

The American system of self-government thus comes to focus in the presidency— “the vital place of action in the system,” as Woodrow Wilson put it. Henry Adams, himself the great-grandson and grandson of presidents as well as a truly brilliant American historian, said that the American president “resembles the commander of a ship at sea. He must have a helm to grasp, a course to steer, a port to seek.”

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a statesman whose massive achievements tower over the twentieth century. In a ranking of American presidents, he is rivaled only by George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. He was elected to an unprecedented four terms in office, and his accomplishments in leading the nation through the depression and a world war resonate to this day.

Roosevelt’s presidency was one of the most eventful in U.S. history. He took office in the midst of economic crisis: the stock market had crashed, the banking system had collapsed, and millions of Americans were unemployed. Galvanizing the nation with his 1933 inaugural address and with a flurry of legislation in the First Hundred Days, Roosevelt demonstrated an optimism and resolve that garnered quick support for his administration and for the programs that he called the New Deal. And he was the first president truly to understand the power of the new mass media, rallying the nation through “fireside chats” on the radio and speeches that were the mainstay of movie house newsreels.

In acute, stylish prose, Roy Jenkins—who was a prominent British politician as well as a bestselling historian—tackles all of the complexities and intricacies of Roosevelt’s character in his short biography, “Franklin Delano Roosevelt,” a 2003 entry in the American Presidents series published by Times Books and Henry Holt and Company. Though not an intellectual himself, Roosevelt was nonetheless able to inspire the intellectual classes. He was from the American upper class, and yet his greatest talent was his ability to inspire confidence among working people during a time of economic and international turmoil. He did that by being honest and trustworthy. And when he had to shift his priorities after Pearl Harbor from (in his words) “Dr. New Deal” to “Dr. Win-the War,” he did so without any loss in the people’s confidence.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the dominant president of the twentieth century, helped the United States become the most influential world power. Roy Jenkins’s keen assessment enables us to understand how he accomplished this and why he still stands tall in our estimation today.

For more information about the Roosevelts, the JSF has six excellent books in stock. Contact the Jesse Stuart Foundation at 4440 13th Street in Ashland by phone at 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

James M. Gifford, Ph.D.

CEO & Senior Editor

Jesse Stuart Foundation