Following World War I, our nation entered a decade of national prosperity. Businesses flourished, and the standard of living rose. Jobs were plentiful and Americans were better fed, clothed, and housed than they had ever been before. During the “Golden Twenties,” Americans also experienced profound changes in societal and moral values. Our nation became more urban and industrial, and the protestant ethic was replaced, in many places, by a more permissive society.

However, the prosperity of the “roaring twenties” did not filter down to the rural poor of Appalachia. When Jack Ellis was born to Lon and Dot Ellis in 1927, the family lived near Morehead, Kentucky, in a “dilapidated, leaky, rat-infested house with no screens on the windows and one room that had a dirt floor.” By the time Jack entered grade school, America was mired in the Great Depression. During the 30s, his father was employed by the Civilian Conservation Corps for several years, but his mother became discouraged and depressed after losing her teaching position in the Rowan County schools.

However, the prosperity of the “roaring twenties” did not filter down to the rural poor of Appalachia. When Jack Ellis was born to Lon and Dot Ellis in 1927, the family lived near Morehead, Kentucky, in a “dilapidated, leaky, rat-infested house with no screens on the windows and one room that had a dirt floor.” By the time Jack entered grade school, America was mired in the Great Depression. During the 30s, his father was employed by the Civilian Conservation Corps for several years, but his mother became discouraged and depressed after losing her teaching position in the Rowan County schools.

In 1940, Jack began his freshman year in high school. The following year, when he was within one month of his fifteenth birthday, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and American life changed dramatically for Jack and the young men and women of his generation, many of whom served for the duration of the war. It was one of the darkest and most painful periods of American history. On battlefields across the world – at Corregidor, Bastogne, Bataan, and thousands of other death sites – young Americans felt especially alone at Christmas. It was a desperate time for our nation, for our soldiers, and for millions of families who were separated from their sons and daughters during five Christmas seasons.

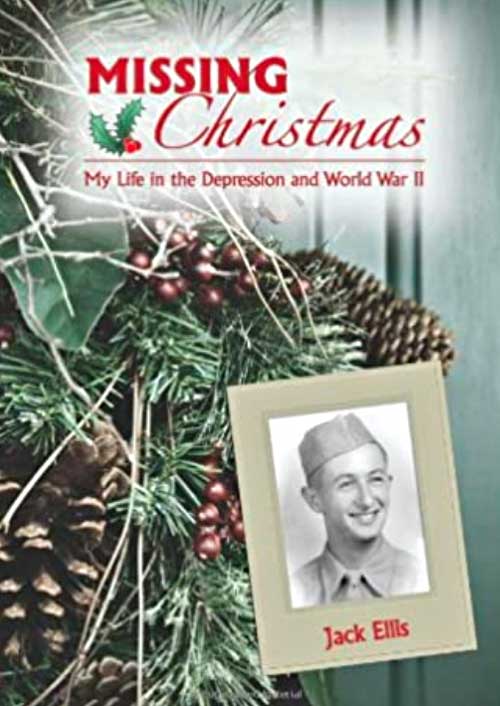

Jack Ellis did not see himself as a hero, but just another GI doing his best to serve and survive. He missed three Christmases at home during World War II. Like millions of fellow GIs, the song “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” had special meaning; the last two lines were

I’ll be home for Christmas,

If only in my dreams.

For three consecutive years Jack missed Christmas at home with his family. But he did arrive in Morehead on New Year’s Eve, 1946. That meant he would not be home for Christmas until 1947. That was the song he sang before entering active duty in the ASTP in 1944. As he stepped off the train and was finally home, he breathed a prayer of thanksgiving. When he walked into his home, his parents were shocked and happy to see him. They did not even know he was in the States. After two-and-on-half years in WWII, and the Army of occupation in Germany, he was still a teenager and would not turn 20 for another 10 days. His military service was over and he was a civilian again. Jack had been the youngest man in the 32nd Troop Carrier Squadron. Fifty years later he attended a squadron reunion in New York.

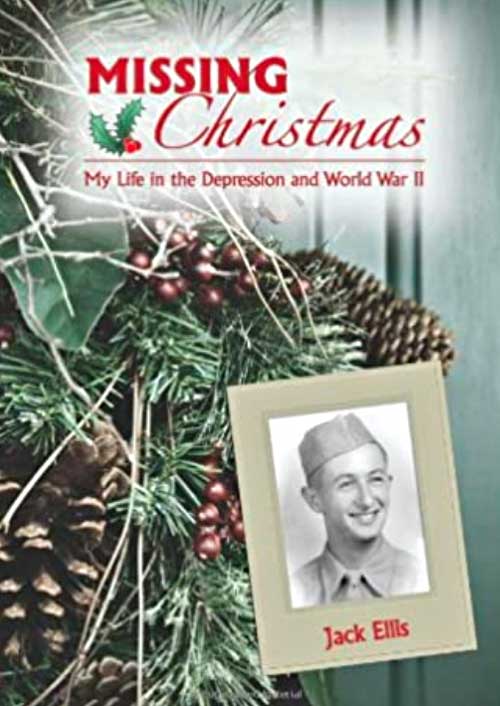

“Missing Christmas: My Life in the Depression and World War II” details Ellis’ experiences during the depression and World War II. This book is more than just a testimony to one man’s service. It honors every man and woman who served our country during World War II. They were an extraordinary generation. They won the war, enforced the peace, and proudly led our country through the second half of the twentieth century. Sixteen million served in the armed forces, and countless millions more supported them at home. Through military service, the “greatest generation” learned lessons of teamwork, initiative, sacrifice, and self-discipline. They came home trained and experienced, put the horrors of war behind them, and built an even greater nation.

Today, most of the World War II generation has marched into the pages of history. As a token of our gratitude and respect for the late Jack Ellis and every member of America’s greatest generation, the Jesse Stuart Foundation was proud to publish this book in 2010.

Members of the Greatest Generation, we salute you!

First edition copies of “Missing Christmas” are available for $20 per copy at the JSF at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, contact the JSF at 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Following World War I, our nation entered a decade of national prosperity. Businesses flourished, and the standard of living rose. Jobs were plentiful and Americans were better fed, clothed, and housed than they had ever been before. During the “Golden Twenties,” Americans also experienced profound changes in societal and moral values. Our nation became more urban and industrial, and the protestant ethic was replaced, in many places, by a more permissive society.

However, the prosperity of the “roaring twenties” did not filter down to the rural poor of Appalachia. When Jack Ellis was born to Lon and Dot Ellis in 1927, the family lived near Morehead, Kentucky, in a “dilapidated, leaky, rat-infested house with no screens on the windows and one room that had a dirt floor.” By the time Jack entered grade school, America was mired in the Great Depression. During the 30s, his father was employed by the Civilian Conservation Corps for several years, but his mother became discouraged and depressed after losing her teaching position in the Rowan County schools.

In 1940, Jack began his freshman year in high school. The following year, when he was within one month of his fifteenth birthday, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and American life changed dramatically for Jack and the young men and women of his generation, many of whom served for the duration of the war. It was one of the darkest and most painful periods of American history. On battlefields across the world – at Corregidor, Bastogne, Bataan, and thousands of other death sites – young Americans felt especially alone at Christmas. It was a desperate time for our nation, for our soldiers, and for millions of families who were separated from their sons and daughters during five Christmas seasons.

Jack Ellis did not see himself as a hero, but just another GI doing his best to serve and survive. He missed three Christmases at home during World War II. Like millions of fellow GIs, the song “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” had special meaning; the last two lines were

I’ll be home for Christmas,

If only in my dreams.

For three consecutive years Jack missed Christmas at home with his family. But he did arrive in Morehead on New Year’s Eve, 1946. That meant he would not be home for Christmas until 1947. That was the song he sang before entering active duty in the ASTP in 1944. As he stepped off the train and was finally home, he breathed a prayer of thanksgiving. When he walked into his home, his parents were shocked and happy to see him. They did not even know he was in the States. After two-and-on-half years in WWII, and the Army of occupation in Germany, he was still a teenager and would not turn 20 for another 10 days. His military service was over and he was a civilian again. Jack had been the youngest man in the 32nd Troop Carrier Squadron. Fifty years later he attended a squadron reunion in New York.

“Missing Christmas: My Life in the Depression and World War II” details Ellis’ experiences during the depression and World War II. This book is more than just a testimony to one man’s service. It honors every man and woman who served our country during World War II. They were an extraordinary generation. They won the war, enforced the peace, and proudly led our country through the second half of the twentieth century. Sixteen million served in the armed forces, and countless millions more supported them at home. Through military service, the “greatest generation” learned lessons of teamwork, initiative, sacrifice, and self-discipline. They came home trained and experienced, put the horrors of war behind them, and built an even greater nation.

Today, most of the World War II generation has marched into the pages of history. As a token of our gratitude and respect for the late Jack Ellis and every member of America’s greatest generation, the Jesse Stuart Foundation was proud to publish this book in 2010.

Members of the Greatest Generation, we salute you!

First edition copies of “Missing Christmas” are available for $20 per copy at the JSF at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, contact the JSF at 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor