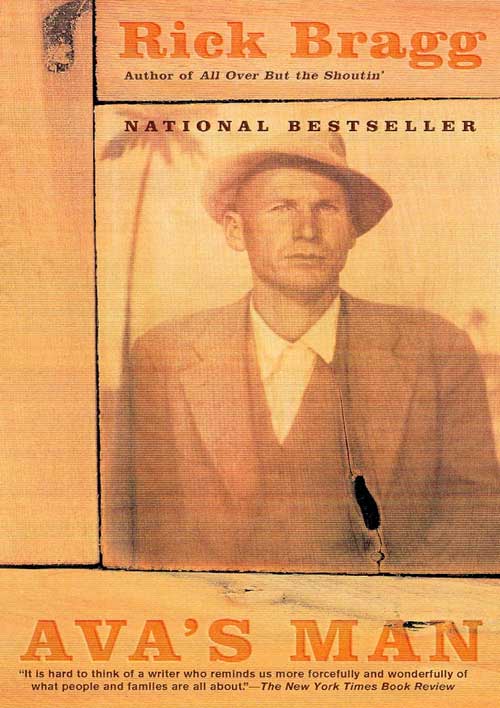

Rick Bragg, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “All Over but the Shoutin’,” continues his personal history of the South with an evocation of his mother’s childhood in the Appalachian foothills during the Great Depression.

The book is “Ava’s Man,” the powerful story of Charlie Bundrum, the author’s grandfather. Charlie was a tall, bone-thin man who worked with nails in his mouth and a roofing hatchet in a fist as hard as Augusta brick, who ran a trot-line across the Coosa River baited with chicken guts and caught washtubs full of catfish. He cooked good white whiskey in the pines, drank his own product and sang, laughed, and buck-danced under the stars. He was a man whose tender heart was stitched together with steel wire, who stood beaten and numb over a baby’s grave in Georgia, then took a simple-minded man into his home to protect him from scoundrels who liked to beat him for fun. He was a country man who inspired legends and the kind of loyalty that still makes old men dip their heads respectfully when they say his name, but he was “bad to drink” and miss his turn into the driveway and run over his own mailbox.

The book is “Ava’s Man,” the powerful story of Charlie Bundrum, the author’s grandfather. Charlie was a tall, bone-thin man who worked with nails in his mouth and a roofing hatchet in a fist as hard as Augusta brick, who ran a trot-line across the Coosa River baited with chicken guts and caught washtubs full of catfish. He cooked good white whiskey in the pines, drank his own product and sang, laughed, and buck-danced under the stars. He was a man whose tender heart was stitched together with steel wire, who stood beaten and numb over a baby’s grave in Georgia, then took a simple-minded man into his home to protect him from scoundrels who liked to beat him for fun. He was a country man who inspired legends and the kind of loyalty that still makes old men dip their heads respectfully when they say his name, but he was “bad to drink” and miss his turn into the driveway and run over his own mailbox.

He was a twentieth century frontiersman. He beat a fellow half to death for throwing a live snake at his son, and he shot a large woman with a .410 shotgun when she tried to cut him with a butcher knife. He whipped two Georgia highway patrolmen and threw them headfirst out the front door of a beer joint called the Maple on the Hill. He was a man who led deputies on long, hapless chases across high, lonesome ridges and through brier-choked bogs, whose hands were so quick he snatched squirrels from trees, who hunted without regard to seasons or quotas, because how could a game warden in Montgomery or Atlanta know if his babies were hungry?

He was a man who could not read but always asked his wife Ava to read the newspaper to him so he would not be ignorant. He died in the spring of 1958, one year before his brilliant grandson and biographer, Rick Bragg, was born.

In the decade of the Great Depression, Charlie Bundrum moved his family twenty-one times, keeping seven children one step ahead of the poverty and starvation that threatened them from every side. He worked at the steel mill when the steel was rolling, or for a side of bacon or a bushel of peaches when it wasn’t. He paid the doctor who delivered his fourth daughter with a jar of whiskey. He understood the finer points of the law as it applied to poor people and drinking men.

Charlie Bundrum had a talent for living. His children revered him. At his funeral, cars lined the blacktop for more than a mile.

“Ava’s Man” is a powerfully intimate piece of American history as it was experienced by working people of the Appalachian foothills early in the twentieth century. It is a stunning book, perhaps the best book I have ever read. I would swap every book I have ever written to be the author of one book as good as “Ava’s Man.” It will help you appreciate your own life, and it will make you cry.

“Ava’s Man” is available in the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore at 4440 13th Street in Ashland or you can purchase it on this website. For more information email sales@jsfbooks.com, or call 606-326-1667.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

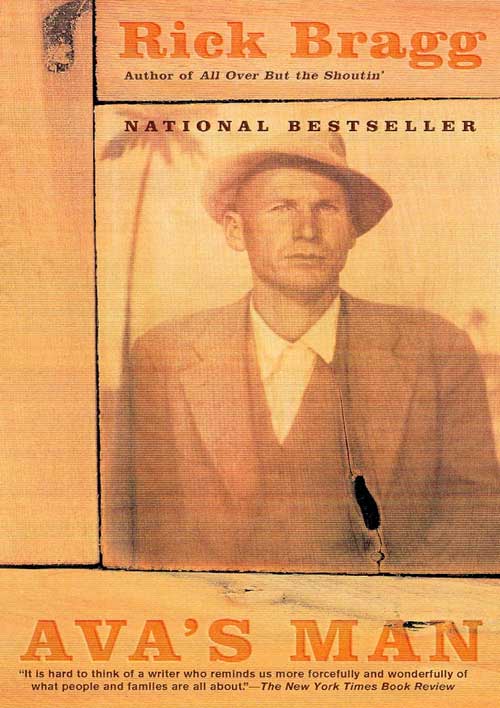

Rick Bragg, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “All Over but the Shoutin’,” continues his personal history of the South with an evocation of his mother’s childhood in the Appalachian foothills during the Great Depression.

The book is “Ava’s Man,” the powerful story of Charlie Bundrum, the author’s grandfather. Charlie was a tall, bone-thin man who worked with nails in his mouth and a roofing hatchet in a fist as hard as Augusta brick, who ran a trot-line across the Coosa River baited with chicken guts and caught washtubs full of catfish. He cooked good white whiskey in the pines, drank his own product and sang, laughed, and buck-danced under the stars. He was a man whose tender heart was stitched together with steel wire, who stood beaten and numb over a baby’s grave in Georgia, then took a simple-minded man into his home to protect him from scoundrels who liked to beat him for fun. He was a country man who inspired legends and the kind of loyalty that still makes old men dip their heads respectfully when they say his name, but he was “bad to drink” and miss his turn into the driveway and run over his own mailbox.

He was a twentieth century frontiersman. He beat a fellow half to death for throwing a live snake at his son, and he shot a large woman with a .410 shotgun when she tried to cut him with a butcher knife. He whipped two Georgia highway patrolmen and threw them headfirst out the front door of a beer joint called the Maple on the Hill. He was a man who led deputies on long, hapless chases across high, lonesome ridges and through brier-choked bogs, whose hands were so quick he snatched squirrels from trees, who hunted without regard to seasons or quotas, because how could a game warden in Montgomery or Atlanta know if his babies were hungry?

He was a man who could not read but always asked his wife Ava to read the newspaper to him so he would not be ignorant. He died in the spring of 1958, one year before his brilliant grandson and biographer, Rick Bragg, was born.

In the decade of the Great Depression, Charlie Bundrum moved his family twenty-one times, keeping seven children one step ahead of the poverty and starvation that threatened them from every side. He worked at the steel mill when the steel was rolling, or for a side of bacon or a bushel of peaches when it wasn’t. He paid the doctor who delivered his fourth daughter with a jar of whiskey. He understood the finer points of the law as it applied to poor people and drinking men.

Charlie Bundrum had a talent for living. His children revered him. At his funeral, cars lined the blacktop for more than a mile.

“Ava’s Man” is a powerfully intimate piece of American history as it was experienced by working people of the Appalachian foothills early in the twentieth century. It is a stunning book, perhaps the best book I have ever read. I would swap every book I have ever written to be the author of one book as good as “Ava’s Man.” It will help you appreciate your own life, and it will make you cry.

“Ava’s Man” is available in the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore at 4440 13th Street in Ashland or you can purchase it on this website. For more information email sales@jsfbooks.com, or call 606-326-1667.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor