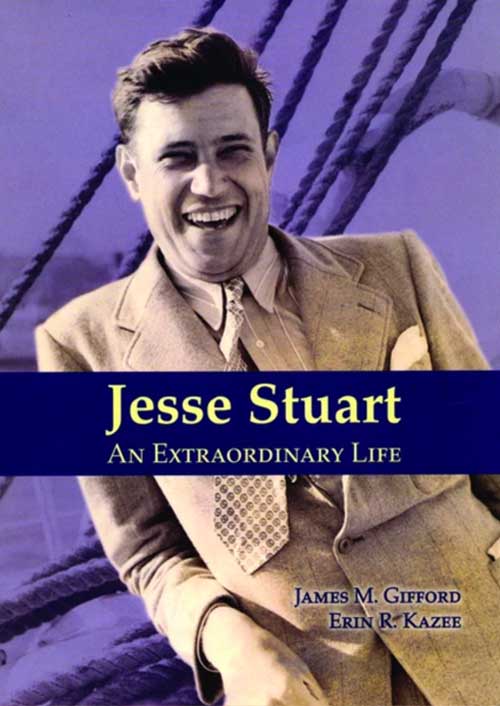

Jesse Stuart was an Appalachian original—a marvelously prolific writing man. Our fretful and fearful twenty-first century is not sure how to classify him or how to value him. So he is often ignored. But America cannot continue to ignore Stuart, for he is a great natural force, like Niagara Falls or old Faithful. Today, long after his death in 1984, Stuart’s words offer hope and direction to thousands and thousands of Americans who take time from their entertainment-addicted lives to read his books, articles, essays, and poems.

Stuart’s father once told him, “There’s no surer way on earth to make a living than between the handles of a plow. But I want you to learn to read, write and cipher.” Though his father could neither read nor write, Stuart said, “my father was really my first teacher” and he often wrote of that marvelous relationship with his father-mentor and other subsequent teachers in his book “To Teach, To Love,” an autobiographical book

Stuart’s father once told him, “There’s no surer way on earth to make a living than between the handles of a plow. But I want you to learn to read, write and cipher.” Though his father could neither read nor write, Stuart said, “my father was really my first teacher” and he often wrote of that marvelous relationship with his father-mentor and other subsequent teachers in his book “To Teach, To Love,” an autobiographical book

In the preface, he said to parents and teachers: “This much I know: Love, a spirit of adventure and excitement, a sense of mission has to get back into the classroom. Without it our schools—and our country—will die.” As a teacher in the hills of Greenup County, he learned that loving students required a firm, even tough, approach at times. With appropriate mixtures of firmness and gentleness, he discovered that both love of learning and respect for the teacher could be achieved. He wrote about his early experiences in the classroom in his world-famous autobiography, “The Thread That Runs So True,” which he dedicated to the teachers of America.

“No one,” he wrote in that book, “can ever tell me that education, rightly directed without propaganda, cannot change the individual, community, county, state, and the world for the better.” Stuart found he could not make a sufficient living as a teacher—a persistent malady of his time—and he went on to other pursuits. He farmed, lectured, and wrote more than 60 books, “but my heart was always in the schoolroom,” he said.

A scholar once observed about Stuart and his life: “The world doesn’t quite know what to do with Jesse Stuart, but he stands among us like a great Niagara of abundance, variety, and scope.” That is an apt description of a writer who fits no single category, but whose genius was reflected in so many genres. In 1971 Stuart told an interviewer, “My idea was to write of my country, my area, which is Appalachia, so my readers over America will know my region and her people.” He knew that his culture and beliefs were important to the strength of the nation.

He concluded that interview by saying, “I would like to see us come back to something good and valuable on this earth. If and when we do that as a nation, it will happen in great measure through our teachers.” Jesse Stuart’s legacy provides a guiding light for America’s future. He presented a universal truth when he wrote, “Good teaching is forever, and the teacher is immortal.” He was a living example.

Jesse Stuart’s books are available in the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

James M. Gifford, Ph.D.

CEO & Senior Editor

Jesse Stuart Foundation

I have served this community faithfully and professionally for forty years. Among my many donations to literacy and learning are more than 500 articles I have written for the Daily Independent. In 2025, I intend to include material from several of my writerly friends among my every-other-week essays.

Nearly twenty years ago, my late friend, Billy C. Clark, noted Appalachian author and educator and a native of Catlettsburg, wrote this article about his second cousin, Jesse Stuart.

I had gone to W-Hollow to visit my cousins, Jesse and Jim Stuart. Jesse’s brother Jim always made it a point to be there whenever I was coming. Jim was special to me, a great educator and man of the soil. He was the gardener of the Stuarts and we talked of the weather, the soil, greasy beans, and the sort. My visits always started the same way, a stop at Jesse’s where he and Jim matched me up against a picture of Uncle Mitch that hung on the wall. “I tell you, Jesse,” Jim would say, “He’s a spittin image of Dad, more Stuart looking than any of us.”

“I told you that first time I laid eye on him,” Jesse said. “And his mother, blood cousin Bertha, looks the same. She’s the last on that side of the family, you know.”

They were both right. I did favor Uncle Mitch. I had fond memories of him, for I had known him longer than any of his family. Come hell or high water, Uncle Mitch made a yearly “up river” visit to see Mom until he could no longer make the trip—a journey of about 20 miles but a world away in those early days of difficult transportation. A young boy back then Uncle Mitch had long singled me out. “This’n be something one day,” he would tell Mom, coaxing to take me home to Greenup County with him. But he knew Mom would not let me go. Stuarts held to their children like bark to a tree. “I couldn’t do without him,” Mom would say. “He’s a help to me, soon as have him in the garden with me as anyone I know. He’s done took to the river and hills. He’s Stuart enough here with me.”

Through Uncle Mitch, I came to know Jesse—20 years my elder—and Jim and all the other Stuarts, and we all became closer.

On this particular summer day of my visit, Jesse suggested we take a walk over the ridge from his house to check on a spring that furnished water for his cattle. That’s what he told Deane [his wife, Naomi Deane Norris Stuart]. But once over the rise he squinted back to make sure his house was out of sight. Satisfied, he reached in his pocket and pulled out a sack of hard-rock candy.

“You’re not supposed to eat sweets, Jesse, you know that,” Jim said. “Doctor has warned against it. But being you’ve brought it into the open, what flavor you got?”

“Whatever flavor you want,” Jesse said, grinning.

“I’ll have to lie about your eating it later on,” Jim said. “Might as well make a lie worthwhile. I’ll take peppermint.”

“And you, Billy,” Jesse said.

“I guess I’ll be lying over horehound if you’ve got a piece,” I answered.

Candy eaten, we sat on the ground and talked weather, the song of birds, the wind and earth and chance of rain. Jesse lit up a cigar—which he loved—drawing the smoke in with great pleasure, giving it to the wind, knowing the wind carried the smoke out of the hollow away from the house erasing the need to lie. I joined him with my pipe, adding a little Kentucky burley to hold a fire in the bowl.

Our talk worked its way around to education. Our talks always did. Both Jim and Jesse were great educators and I was working my way up. Our talks also dealt with writing, but never our own. We never discussed our personal writings with one another.

At this point in his life, Jesse was one of the giants of American literature: a writer in the company of Hemingway, Steinbeck, and other contemporaries. But with a cleanness far beyond most of them. Jesse’s words were filtered as clean as the spring where we chose to sit and talk. He had the gift of storytelling, his setting and characters close to his heart. His works captured his land and his people with universality of theme in the nature of Burns, Frost, Kipling, and Twain, especially Twain.

One of Jesse’s most famous quotes was that a teacher becomes “immortal” through his students. I agree with Jesse. But I would be quick to add that his immortality as an educator is intensified by his brilliant poems and stories that defined a land and a people.

My thoughts of Jesse remind me that Ruth and I were married at Jesse’s home forty-nine years ago. Jesse was my best man, and Deane was the matron of honor. During the reception, Jim sneaked off and tied cans to our car rattling us out of W-Hollow. The Stuarts are still rattling around in my memory today. [November 2005]

Books by and about both Jesse Stuart and Billy C. Clark are included among thousands in the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor