I am proud to present this article as the Jesse Stuart Foundation’s tribute to Black History Month. February was chosen as Black History Month because Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, two men who played important roles in abolishing slavery in the United States, were born in February.

Before the Civil War, the Underground Railroad was a network of hundreds of safe houses throughout the North and South that served as hiding places on the road to freedom for tens of thousands of runaway slaves who risked their lives in a long, hazardous journey, often on foot, that frequently stretched more than one thousand miles. It is also the story of perseverance, bravery, and humanity in which thousands of whites risked social scorn, business setbacks, arrests, fines, prison, and even death to assist runaway slaves.

Before the Civil War, the Underground Railroad was a network of hundreds of safe houses throughout the North and South that served as hiding places on the road to freedom for tens of thousands of runaway slaves who risked their lives in a long, hazardous journey, often on foot, that frequently stretched more than one thousand miles. It is also the story of perseverance, bravery, and humanity in which thousands of whites risked social scorn, business setbacks, arrests, fines, prison, and even death to assist runaway slaves.

Because of its dangerous and highly secretive nature, there were no records of the “conductors” on the Underground Railroad nor was there a list of the “depots.” No one really knew (or knows) how extensive it was. The Underground Railroad became legendary when the war ended and newspapers and magazines reported its success in glowing detail. Some claimed that over one million slaves escaped to freedom on the Underground Railroad, but today’s scholars think the actual numbers range between 40,000 and 100,000.

Runaways risked everything. Mothers urged their sons to flee, never to see them again. Parents sent their children off with friends, knowing it was the last time they would embrace. Sometimes entire families traveled North together.

Runaways lived in fear. They traveled mainly at night, stumbling through rock-filled creeks, trying to navigate their way through meadows, thickets, and forests, hiding every time they heard the sound of horses’ hooves or carriage wheels on darkened roads. They slept little as they moved from home to home, barn to barn, church to church.

The northerners who assisted them devised inventive hideaways for the fugitives. One abolitionist, whose home was built near the Ohio River, dug an underground tunnel from the basement of his house to the riverbank so that slaves could flee unobserved if slavecatchers arrived. Many homes in Kentucky and Ohio contained secret rooms to hide escaped slaves.

The Underground Railroad eventually had over five hundred safe houses. For many years, the story of the Underground Railroad gradually faded from public memory, but during the last few decades, historical and civic organizations have given it new life.

Today, many of the original sites have been restored and are open to individuals and tour groups, as a new generation of people are heartened by the triumphant story of blacks and whites who worked together for freedom so long ago.

Some of the Underground Railroad sites are within easy driving distance of the Ashland area, including the National Underground Railroad Museum in Maysville, several homes in Southern Ohio, and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio.

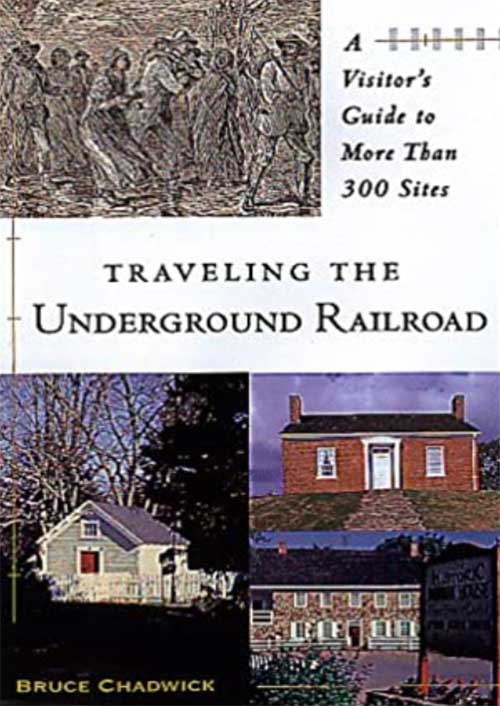

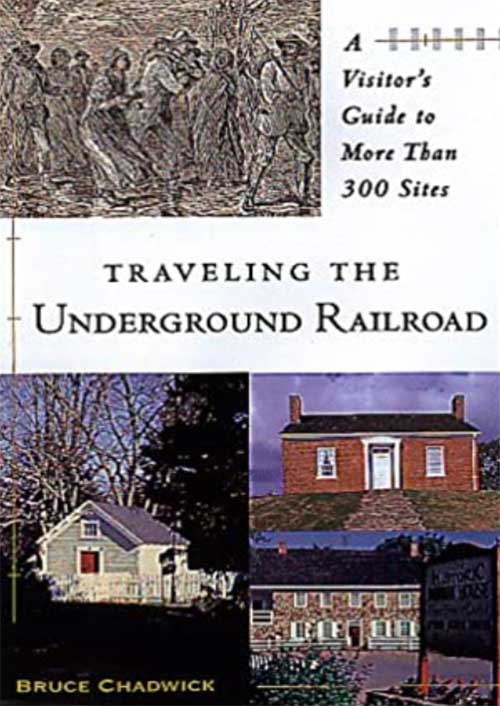

If you are interested in reading more about this fascinating part of our national and regional experience, the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Appalachian Gift Shop, located at 4440 13th Street in Ashland, has in stock “Traveling the Underground Railroad” by Bruce Chadwick, a visitors’ guide to more than 300 sites. It contains an excellent historical Introduction. This book is available on this website and at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Gift Shop at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, contact the JSF at 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

I am proud to present this article as the Jesse Stuart Foundation’s tribute to Black History Month. February was chosen as Black History Month because Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, two men who played important roles in abolishing slavery in the United States, were born in February.

Before the Civil War, the Underground Railroad was a network of hundreds of safe houses throughout the North and South that served as hiding places on the road to freedom for tens of thousands of runaway slaves who risked their lives in a long, hazardous journey, often on foot, that frequently stretched more than one thousand miles. It is also the story of perseverance, bravery, and humanity in which thousands of whites risked social scorn, business setbacks, arrests, fines, prison, and even death to assist runaway slaves.

Because of its dangerous and highly secretive nature, there were no records of the “conductors” on the Underground Railroad nor was there a list of the “depots.” No one really knew (or knows) how extensive it was. The Underground Railroad became legendary when the war ended and newspapers and magazines reported its success in glowing detail. Some claimed that over one million slaves escaped to freedom on the Underground Railroad, but today’s scholars think the actual numbers range between 40,000 and 100,000.

Runaways risked everything. Mothers urged their sons to flee, never to see them again. Parents sent their children off with friends, knowing it was the last time they would embrace. Sometimes entire families traveled North together.

Runaways lived in fear. They traveled mainly at night, stumbling through rock-filled creeks, trying to navigate their way through meadows, thickets, and forests, hiding every time they heard the sound of horses’ hooves or carriage wheels on darkened roads. They slept little as they moved from home to home, barn to barn, church to church.

The northerners who assisted them devised inventive hideaways for the fugitives. One abolitionist, whose home was built near the Ohio River, dug an underground tunnel from the basement of his house to the riverbank so that slaves could flee unobserved if slavecatchers arrived. Many homes in Kentucky and Ohio contained secret rooms to hide escaped slaves.

The Underground Railroad eventually had over five hundred safe houses. For many years, the story of the Underground Railroad gradually faded from public memory, but during the last few decades, historical and civic organizations have given it new life.

Today, many of the original sites have been restored and are open to individuals and tour groups, as a new generation of people are heartened by the triumphant story of blacks and whites who worked together for freedom so long ago.

Some of the Underground Railroad sites are within easy driving distance of the Ashland area, including the National Underground Railroad Museum in Maysville, several homes in Southern Ohio, and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio.

If you are interested in reading more about this fascinating part of our national and regional experience, the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Appalachian Gift Shop, located at 4440 13th Street in Ashland, has in stock “Traveling the Underground Railroad” by Bruce Chadwick, a visitors’ guide to more than 300 sites. It contains an excellent historical Introduction. This book is available on this website and at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Gift Shop at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, contact the JSF at 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor