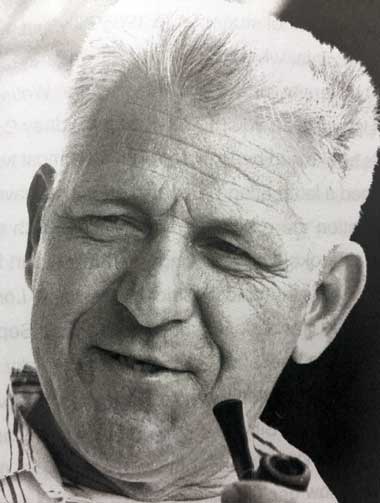

My friend Billy C. Clark died on March 15, 2009. Since then, I have thought of him often. Memories of long trips together or his fanciful stories supercharged with hyperbole always make me smile. The great eastern Kentucky writer and storyteller began his life in storybook fashion.

On December 2, 1928, Bertha Clark traveled by streetcar across a bridge that stood near the present-day Billy C. Clark Bridge in Catlettsburg. Mrs. Clark, who was pregnant with her seventh child, had gone to Huntington, West Virginia, to shop for second-hand clothes for her six children.

On December 2, 1928, Bertha Clark traveled by streetcar across a bridge that stood near the present-day Billy C. Clark Bridge in Catlettsburg. Mrs. Clark, who was pregnant with her seventh child, had gone to Huntington, West Virginia, to shop for second-hand clothes for her six children.

While she was shopping, she experienced labor pains. Quickly gathering up the clothes she had bought, she turned her eyes toward the Big Sandy River. Fearful that her seventh child would be born outside of Kentucky, she boarded the streetcar and headed for home. One thought occupied her mind: she must make it to Kentucky soil. Bertha Clark was determined that her child would not be a “foreigner.”

The streetcar ride was rough, and the bumps in the road brought more pains. As Mrs. Clark gritted her teeth and searched for the Big Sandy, the driver noticed her. “Something wrong, lady?” he asked as he stopped the streetcar to let a passenger off.

“I’m going to have a baby,” she said.

“Hell’s afire, lady!” the driver yelled. “Not here in the streetcar! Hold it! Hold it!”

“How far till we cross the Big Sandy?” she asked in desperation.

“Not far,” the driver answered. “How far do you live from the end of the bridge?”

“Below the mouth of Catlettscreek,” she said.

He slammed the door and pushed the streetcar as fast as it would go. The rest of the passengers shouted and quarreled as the driver passed their stops, refusing to let them off. Now and then he looked over at Mrs. Clark, “Hold it, lady! Hold it just a little longer!”

When Billy Curtis Clark was born on Kentucky soil that day, no one could have foreseen his destiny. He seemed to be just another child born into Appalachian poverty. Billy’s father, Mason, was a cobbler and mountain fiddler. His mother Bertha took in washing and “scrubbed until her hands bled,” but she often gave to needier families.

The seventh born of nine children, Billy was the only one to graduate from high school. He left home when he was eleven years old, and for the next five years, he lived on the third floor of the Court House Building in Catlettsburg. “I cleaned the men’s and women’s jails,” he remembered, “wound the town clock, and served as a volunteer fireman to put myself through high school.” He also fished, trapped, picked berries to sell, and worked at odd jobs.

After high school, a four-year stint in the Army during the Korean War made Billy eligible for educational benefits under the G.I. Bill, and he enrolled at the University of Kentucky in 1953. During his college years, he published “A Heap of Hills” (1956). He was soon publishing in national magazines.

After college, he published five books in five years with commercial publishers: “Song of the River” (1967), “The Trail of the Hunter’s Horn” (1957), “Riverboy” (1958), “Mooneyed Hound” (1959), and “A Long Row to Hoe” (1960).

In the 1960s, Clark published three more well-received books: “Goodbye Kate” (1964), “The Champion of Sourwood Mountain” (1966), and “Sourwood Tales” (1968).

The next four decades of his life were a succession of professional honors and publications.

Now he belongs to the ages. In my mind’s eye, I see him in well-worn fishing garb talking with his heavenly Father: “Lord, I know you’ve been listening in on some of those stories that my Catlettsburg friends have been telling on me. Now here’s what really happened….” And the Lord smiles, wondering if eternity will be quite long enough for Billy Clark to complete his stories.

Like his second cousin Jesse Stuart, Billy C. Clark rose from poverty to become a nationally famous author and educator. His books, particularly his autobiographical book “A Long Row to Hoe,” define the river culture of Appalachia.

“A Long Row to Hoe” is the July selection for the JSF Regional Readers. This book discussion group will meet in the JSF Conference Room on Tuesday, July 27. Coffee and conversation at 2:00 pm; book discussion begins at 2:30 pm. The books group is open to everyone.

The works of Billy C. Clark are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Appalachian Gift Shop at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, call 606.326.1667 or e-mail jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Billy Clark

My friend Billy C. Clark died on March 15, 2009. Since then, I have thought of him often. Memories of long trips together or his fanciful stories supercharged with hyperbole always make me smile. The great eastern Kentucky writer and storyteller began his life in storybook fashion.

On December 2, 1928, Bertha Clark traveled by streetcar across a bridge that stood near the present-day Billy C. Clark Bridge in Catlettsburg. Mrs. Clark, who was pregnant with her seventh child, had gone to Huntington, West Virginia, to shop for second-hand clothes for her six children.

While she was shopping, she experienced labor pains. Quickly gathering up the clothes she had bought, she turned her eyes toward the Big Sandy River. Fearful that her seventh child would be born outside of Kentucky, she boarded the streetcar and headed for home. One thought occupied her mind: she must make it to Kentucky soil. Bertha Clark was determined that her child would not be a “foreigner.”

The streetcar ride was rough, and the bumps in the road brought more pains. As Mrs. Clark gritted her teeth and searched for the Big Sandy, the driver noticed her. “Something wrong, lady?” he asked as he stopped the streetcar to let a passenger off.

“I’m going to have a baby,” she said.

“Hell’s afire, lady!” the driver yelled. “Not here in the streetcar! Hold it! Hold it!”

“How far till we cross the Big Sandy?” she asked in desperation.

“Not far,” the driver answered. “How far do you live from the end of the bridge?”

“Below the mouth of Catlettscreek,” she said.

He slammed the door and pushed the streetcar as fast as it would go. The rest of the passengers shouted and quarreled as the driver passed their stops, refusing to let them off. Now and then he looked over at Mrs. Clark, “Hold it, lady! Hold it just a little longer!”

When Billy Curtis Clark was born on Kentucky soil that day, no one could have foreseen his destiny. He seemed to be just another child born into Appalachian poverty. Billy’s father, Mason, was a cobbler and mountain fiddler. His mother Bertha took in washing and “scrubbed until her hands bled,” but she often gave to needier families.

The seventh born of nine children, Billy was the only one to graduate from high school. He left home when he was eleven years old, and for the next five years, he lived on the third floor of the Court House Building in Catlettsburg. “I cleaned the men’s and women’s jails,” he remembered, “wound the town clock, and served as a volunteer fireman to put myself through high school.” He also fished, trapped, picked berries to sell, and worked at odd jobs.

After high school, a four-year stint in the Army during the Korean War made Billy eligible for educational benefits under the G.I. Bill, and he enrolled at the University of Kentucky in 1953. During his college years, he published “A Heap of Hills” (1956). He was soon publishing in national magazines.

After college, he published five books in five years with commercial publishers: “Song of the River” (1967), “The Trail of the Hunter’s Horn” (1957), “Riverboy” (1958), “Mooneyed Hound” (1959), and “A Long Row to Hoe” (1960).

In the 1960s, Clark published three more well-received books: “Goodbye Kate” (1964), “The Champion of Sourwood Mountain” (1966), and “Sourwood Tales” (1968).

The next four decades of his life were a succession of professional honors and publications.

Now he belongs to the ages. In my mind’s eye, I see him in well-worn fishing garb talking with his heavenly Father: “Lord, I know you’ve been listening in on some of those stories that my Catlettsburg friends have been telling on me. Now here’s what really happened….” And the Lord smiles, wondering if eternity will be quite long enough for Billy Clark to complete his stories.

Like his second cousin Jesse Stuart, Billy C. Clark rose from poverty to become a nationally famous author and educator. His books, particularly his autobiographical book “A Long Row to Hoe,” define the river culture of Appalachia.

“A Long Row to Hoe” is the July selection for the JSF Regional Readers. This book discussion group will meet in the JSF Conference Room on Tuesday, July 27. Coffee and conversation at 2:00 pm; book discussion begins at 2:30 pm. The books group is open to everyone.

The works of Billy C. Clark are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Appalachian Gift Shop at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information, call 606.326.1667 or e-mail jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor