Jesse Stuart was a man of wide-ranging accomplishments. He was a world-famous author, a respected educator, a farsighted conservationist, and an authentic spokesman for his Appalachian homeland. And, like many men and women of his generation, he served in the armed forces during World War II.

In 1942, Jesse, who was thirty-six years old, had failed his physical exam when he tried to join the Army. Two years later, he tried to enter the war again by joining the Navy. This time, he passed his physical exam in Huntington, West Virginia, in February and was sworn in at Louisville on March 31, 1944.

Jesse Stuart

He left immediately for basic training at the Great Lakes Training Command near Chicago and was there for fourteen weeks, missing his daughter Jane, his wife Deane, and their “little home, dogs and chickens.” Jesse dreaded the intense workouts “at [his] age” and losing “the freedom a civilian has in America,” but hoped “to make a good seaman.” He put forth a great effort, running so hard and so often that he lost six and a half pounds in a single week.

On July 12, 1944, a month before his thirty-eighth birthday, he graduated and was commissioned as a Lieutenant Junior Grade (LT JG). He was assigned to the Bureau of Aeronautics in Washington, D.C., where he worked until the war ended.

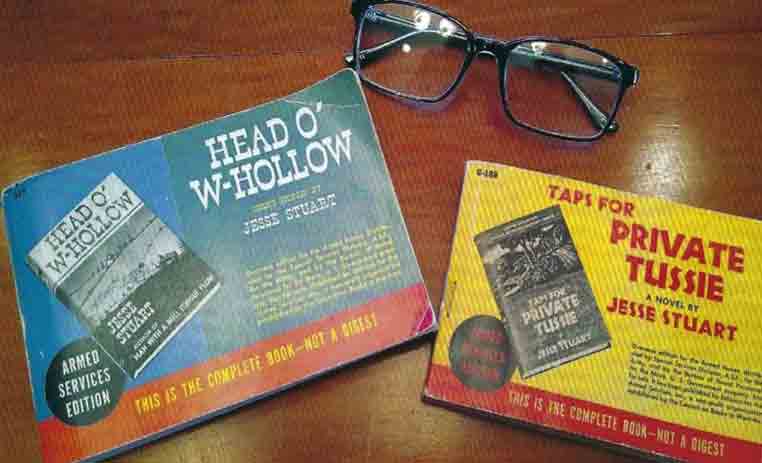

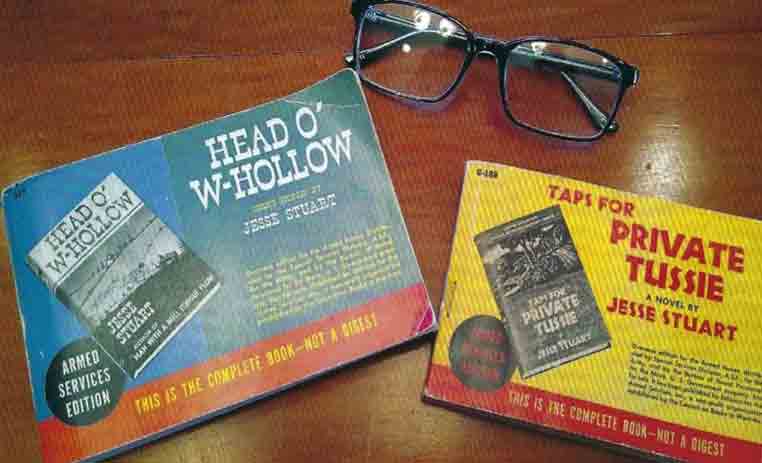

Although Jesse Stuart never served overseas, two of his books provided special inspiration to American soldiers far from home. Stuart’s novel, “Taps For Private Tussie,” and his short story collection, “Head O’ W-Hollow,” were two of 1,322 titles that were published as Armed Services Editions for American service men during World War II.

Between 1943 and 1947, almost 123 million copies of these pocket-sized paperbacks were distributed to members of the U.S. Armed Forces around the world. These books covered a wide range of topics, including popular best sellers, mysteries, classics, history books, westerns, and even poetry. They enjoyed an enthusiastic reading audience of young men and women who were glad to turn their minds away from war toward thoughts of home.

One World War II veteran became a college professor after the war and later reported that the Armed Services Editions introduced him to “new literary friends,” including Hemingway, Dickens, and Maugham. He still had a half dozen after the war that represented “the most positive of my memories of service days.”

Although most carried these books in their shirt pockets, one soldier remembered carrying a copy of Carl Sandburg’s civil war book, “Storm Over the Land,” in his helmet. “During the lulls in battle [in Saipan], I would read what he wrote about another war and found a great deal of comfort and reassurance.” Years later, the author inscribed the book for him.

The ASE books were everywhere. Soldiers read them while waiting to storm the beaches at Normandy, pinned down in muddy foxholes, and in field hospitals. They read them in the chow lines and on planes and ships. The books were so much a part of the war that one sailor remarked that a man was “out of uniform if one isn’t sticking out of his hip pocket.”

The books were an emotional salvation to young men and women far from home and family. Soldiers often wrote the authors and the authors usually replied. One young Marine with a “dead heart . . . and dulled mind” wrote to Betty Smith, author of “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” that her book revitalized his emotions.

I can’t explain the emotional reaction that took place. I only know that it happened and that this heart of mine turned over and became alive again. I don’t think I would have been able to sleep this night unless I bared my heart to the person who caused it to live again.

Armed Services Editions were only distributed overseas, in order to avoid competition with civilian markets. The authors and publishers each received a one-half cent per copy royalty. Only about 70 of the 1,322 volumes were abridged. Everyone involved in this project agreed that they had done something important to help American soldiers survive the war.

Books symbolized the conflict of World War II. As the Nazi armies stormed across Europe, they burned books and libraries. By the end of the war, more than one hundred million volumes had been destroyed by German soldiers. To counter this attack on books, American librarians encouraged citizens to donate books to our service men and women. Soon the Armed Services Editions filled the pockets, minds, and hearts of millions of soldiers.

Books by Jesse Stuart and other Kentucky and Appalachian authors are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Appalachian Gift Shop. For more information, or to place an order, call 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

Author’s Note: An expanded version of this article appears in the current issue of “Kentucky Humanities.”

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Jesse Stuart was a man of wide-ranging accomplishments. He was a world-famous author, a respected educator, a farsighted conservationist, and an authentic spokesman for his Appalachian homeland. And, like many men and women of his generation, he served in the armed forces during World War II.

In 1942, Jesse, who was thirty-six years old, had failed his physical exam when he tried to join the Army. Two years later, he tried to enter the war again by joining the Navy. This time, he passed his physical exam in Huntington, West Virginia, in February and was sworn in at Louisville on March 31, 1944.

He left immediately for basic training at the Great Lakes Training Command near Chicago and was there for fourteen weeks, missing his daughter Jane, his wife Deane, and their “little home, dogs and chickens.” Jesse dreaded the intense workouts “at [his] age” and losing “the freedom a civilian has in America,” but hoped “to make a good seaman.” He put forth a great effort, running so hard and so often that he lost six and a half pounds in a single week.

On July 12, 1944, a month before his thirty-eighth birthday, he graduated and was commissioned as a Lieutenant Junior Grade (LT JG). He was assigned to the Bureau of Aeronautics in Washington, D.C., where he worked until the war ended.

Jesse Stuart

Although Jesse Stuart never served overseas, two of his books provided special inspiration to American soldiers far from home. Stuart’s novel, “Taps For Private Tussie,” and his short story collection, “Head O’ W-Hollow,” were two of 1,322 titles that were published as Armed Services Editions for American service men during World War II.

Between 1943 and 1947, almost 123 million copies of these pocket-sized paperbacks were distributed to members of the U.S. Armed Forces around the world. These books covered a wide range of topics, including popular best sellers, mysteries, classics, history books, westerns, and even poetry. They enjoyed an enthusiastic reading audience of young men and women who were glad to turn their minds away from war toward thoughts of home.

One World War II veteran became a college professor after the war and later reported that the Armed Services Editions introduced him to “new literary friends,” including Hemingway, Dickens, and Maugham. He still had a half dozen after the war that represented “the most positive of my memories of service days.”

Although most carried these books in their shirt pockets, one soldier remembered carrying a copy of Carl Sandburg’s civil war book, “Storm Over the Land,” in his helmet. “During the lulls in battle [in Saipan], I would read what he wrote about another war and found a great deal of comfort and reassurance.” Years later, the author inscribed the book for him.

The ASE books were everywhere. Soldiers read them while waiting to storm the beaches at Normandy, pinned down in muddy foxholes, and in field hospitals. They read them in the chow lines and on planes and ships. The books were so much a part of the war that one sailor remarked that a man was “out of uniform if one isn’t sticking out of his hip pocket.”

The books were an emotional salvation to young men and women far from home and family. Soldiers often wrote the authors and the authors usually replied. One young Marine with a “dead heart . . . and dulled mind” wrote to Betty Smith, author of “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” that her book revitalized his emotions.

I can’t explain the emotional reaction that took place. I only know that it happened and that this heart of mine turned over and became alive again. I don’t think I would have been able to sleep this night unless I bared my heart to the person who caused it to live again.

Armed Services Editions were only distributed overseas, in order to avoid competition with civilian markets. The authors and publishers each received a one-half cent per copy royalty. Only about 70 of the 1,322 volumes were abridged. Everyone involved in this project agreed that they had done something important to help American soldiers survive the war.

Books symbolized the conflict of World War II. As the Nazi armies stormed across Europe, they burned books and libraries. By the end of the war, more than one hundred million volumes had been destroyed by German soldiers. To counter this attack on books, American librarians encouraged citizens to donate books to our service men and women. Soon the Armed Services Editions filled the pockets, minds, and hearts of millions of soldiers.

Books by Jesse Stuart and other Kentucky and Appalachian authors are available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore & Appalachian Gift Shop. For more information, or to place an order, call 606.326.1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

Author’s Note: An expanded version of this article appears in the current issue of “Kentucky Humanities.”

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor